By Ira Katz

March 12, 2025

The intellectual and moral level of European elites is shockingly low. I say shockingly because as an American I found the European (and British) accents gave a very sophisticated quality to their discourse. Now, after living in France for almost twenty years, they sound as idiotic as the typical US senator. See the recent Macron and Baerbock speeches as prime examples of this descent. Or maybe it is just that I understand the world a bit better now.

I put the current generation in contrast to the generation that came of age in the first-half of the 20the century. It has been over three decades since I read Arthur Koestler's anti-communist novel Darkness at Noon. Just the other day I finished his memoir of the first months of the Second World War (written after his escape to England in 1941), ironically titled Scum of the Earth, referring to himself and the other refugees that the French government rounded up, put into concentration camps, and in many cases subsequently handed over to the Gestapo after the debacle.

Here is a brief description of his life from the Afterward:

Kœstler, like so many of the seminal writers of modern English - Joseph Conrad, Ezra Pound and T S Eliot - first came to these shores as a mature immigrant. In Koestler's case, he fled imprisonment in Nazi-occupied France, as you will just have read in Scum of the Earth. When he was arrested as an undesirable and dangerous alien in Paris on October 4, 1939, he was thirty-four years old and had already made a name for himself as a talented and politically engaged journalist. Kœstler was born in Budapest into a Hungarian Jewish family. As a young man he studied pure science in Vienna, an environment that led him to become a keen Zionist. He was a follower of Vladimir Jobotinsky, the talented right-wing Zionist leader, though once he landed in Palestine he joined a left-wing kibbutz. His stay in the kibbutz lasted only a few weeks; he was too much of an individualist to fit in and not a natural agricultural worker. He spent the next year as a loafer in Haifa and Tel Aviv, drawn to all sorts of unlikely pursuits, such as selling advertising for a new Hebrew-language newspaper, surveying, and writing fairy tales. He was an unlikely citizen of the new nation for he never mastered Hebrew and had only a very limited interest in Jewish tradition, history and culture. He often starved and slept on the floor of offices belonging to friends. Then came a sudden breakthrough - an offer to write for leading German and Austrian newspapers. Within a couple of years he became what he wanted to be - a star journalist. In 1929 he left Palestine for Paris, gradually abandoning Zionism for the world-inclusive creed of Communism. He travelled a great deal, flying in a Zeppelin over the North Pole and making a long stay in the Soviet Union. He became a formal member of the Communist Party in 1931 and a committed activist. His experience of the Spanish Civil War (1936-7) was as a columnist for the London News Chronicle, though it seems that he also had political duties through his position within the Communist International. The confusing ethics of this period, and his experience of imprisonment by the Fascists under sentence of death in Seville, were described in Spanish Testament (1938) which was later reshaped into Dialogue with Death (1942). He formally broke allegiance with the Communist Party in 1938, after the Moscow purges and show trials reached their bizarre conclusion, leaving the Russian army critically weakened at the start of the Second World War. In Paris, after war was declared in 1939, another sort of purge was unleashed. Kœstler along with other liberal free-thinkers, communists and socialist exiles - the ironical 'scum of the earth' of the book's title - were targeted by right-wing elements within the French regime even before the Nazi victory and the swift emergence of French 'Vichy' fascism. Hundreds of writers and political figures were arrested. Some managed to escape but many were caught in the internment camps, committed suicide or were deported to Germany where they were murdered. There was of course no logical reason why Kœstler should have been arrested. As a Jew and a man of the left, his and-Nazi credentials were above suspicion while as a Hungarian (Hungary was a neutral country at the time) he should also have been outside the police dragnet. It is ironic that Darkness at Noon was written in this period, between Koestler's first arrest in Paris and his second in the spring of 1940. His hair-raising escape across the breadth of German-occupied France, to the safety of England, provides the narrative background for Scum of the Earth, which also reveals his mature reflections on the unwritten civil war within European society that was waged through out the '20s and '30s.

Scum of the Earth was Interesting to me, in part, because it is a veritable tour de France, a country that I now call my home. But more so because Koestler epitomized the erudite men and women of action living in the first half of the twentieth century.

Given below are two more passages from Scum of the Earth that recount the horrible and incredible outcomes of the Scum.

On the third day of our stay in the Stadium, the arrival of Fuhrmann, a German Liberal journalist, created some hilarity. Fuhrmann, a man of forty and quite a well-known figure in the Weimar Republic, had been put in a concentration camp by the Gestapo and had escaped a few years ago to Austria. When the Nazi marched into Austria, he escaped to Eger. When Eger was attached to Germany after Munich, he escaped to Prague. When the Nazis occupied Prague, he escaped to Italy. When the war broke out and Italian non-belligerency began, he escaped to France by means of a fishing boat, which took him by night from San Remo to some lonely spot on the French shore near Nice. He had arrived in Paris forty-eight hours ago by train, and gone straight from the railway station to see P., a German refugee and fellow journalist, whose address he knew. He found Mrs. P. at home, who nearly fainted when he walked in. Then she told him that P. was in a concentration camp, that all German refugees had been interned, and that he must get himself interned at once, else he would get into a frightful mess with the police and be put in jail. The best thing he could do was to drive at once to the Stadium at Colombes, the clearing-camp for German internees. She was so panicky that poor Fuhrmann also got the wind up and told the taxi-driver, who had been waiting downstairs with his luggage, to take him at once to Colombes.

We sat around on the bed of the little hotel room, and they told me the news. Feuchtwanger had succeeded in getting to America in some adventurous way. Ernst Weiss, the novelist, had committed suicide by taking veronal in Paris. Walter Hasenclever, the playwright, had committed suicide by opening his veins in a concentration camp near Avignon. Kayser, of the editorial staff of the Pariser Tageszeitung, had swallowed strychnine in another camp. Willi Muenzenberg, one-time head of the Comintern's West-European propaganda section, later enemy No. 1 of the Third International, virtual leader of the German exiles, had disappeared from a concentration camp in Savoy during the German advance and nothing had been heard of him since. (News came a few months later. Muenzenberg was found dead in a forest near Grenoble, with a rope round his neck. Whether he was killed by the German Gestapo, the Russian O.G.P.U., or by his own despair, will probably never be established.)

I have written about J. B. Matthews previously. He is a bit older than Koestler, but also lived an eventful life including his stint as the Director of Research for the Committee on Un-American Activities. In that role he took the testimony of Richard Krebs, better known as Jan Valtin - Wikipedia.

Matthews' widow, Ruth Inglis Matthews, gave me a copy of Valtin's memoir Out of the Night. I was captivated, what a story!

He was born in Germany in 1905. As a teenager in 1923 he joined the Communist Party. He was involved in many street battles. He then began a career as an agent for the Commintern (Communist International). "In 1926, working as a courier, he stowawayed to Victoria, British Columbia and then hitchhiked to San Francisco and made contact with the Comintern. Valtin was assigned to execute someone in Los Angeles, but failed in the attempt, was caught, and sentenced to San Quentin State Prison. During the 1000 days he spent there, he studied Bowditch's American Practical Navigator, astronomy, journalism, map making, English, French, and Spanish. After being released in December 1929, he returned to Europe.

"In January 1931, while in Germany, he participated in the "United action of the Communist Party and the Hitler movement to accelerate the disintegration of the crumbling democratic bloc which governs Germany." After graduating with a navigator's certificate, he was assigned as the Soviet skipper transporting the Pioner from the Bremer Vulkan shipyard to Murmansk."

He returned to Germany in 1933 to participate in street battles against the Nazis. But he also described the tacit pact of the Communists with them to disrupt all of the democratic parties. Valtin also explained the following treachery of Stalin, dealing with the Gestapo to eliminate his potential Communist German rivals.

Krebs was arrested by the Gestapo in 1933 and was psychologically broken by them in 1934. While still in the hands of the Gestapo, the Soviets ordered him to turn his allegiance and work for the Gestapo, in effect to become a double agent.

In 1938 he was able to leave Germany and the Gestapo behind. But then he was arrested by the Soviet GPU in Copenhagen. When he learned that his wife had died in a German concentration camp he became disenchanted with communism. He was able to escape from the GPU and returned to the US where he then wrote and published Out of the Night which became a big success.

In 1941 he gave his testimony to the HUAC; but In 1942 he was arrested in the US, though later acquitted, for being a Gestapo agent. Krebs was drafted as an infantryman and deployed in February 1944 to the Philippines and saw combat in fighting the Japanese in the Pacific War.

After all of these adventures Richard Krebs/Jan Valtin died of natural causes in 1951.

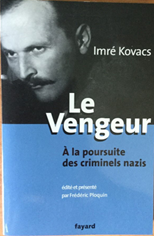

Le Vengeur by Emiré Kovacs is one of the first books I read in French as there is no English translation. My French journalist wife is a friend of Kovacs' journalist son who only found the transcript after his father's death.

An Amazon reviewer sums up his life very well, as translated by Google with my notes in square brackets:

... Imré Kovacs recounts an absolutely incredible destiny. Born in Hungary to a non-practicing Jewish family, forced to fend for himself as an adult from the age of 10 after the death of his father, still a teenager at the start of the war, Kovacs would survive the Holocaust, enlist under a false name in the Waffen SS on behalf of a Zionist organization [recruited because he looked Aryan], be arrested [rather taken as a POW] by the Russians and deported to a labor camp, then escape clandestinely to Palestine. After serving in the Stern Group and surviving the 1948 Arab-Israeli War (he vividly recalls that many immigrants from Eastern Europe had landed by boat at night, had been given a rifle and had died "before seeing the sun rise over Israel"), he refused to remain in the Israeli army. Many after these events would have sought respite. Kovacs, himself, went to Marseille to join the Foreign Legion, which led him to fight in Indochina (up to Điện Biên Phủ) and in Algeria [see Algerian War - Wikipedia or my article The Battle of Algiers - LewRockwell] for another 5 years. It was only after returning from Algeria that he married and became a waiter for 30 years at the Lipp brasserie in Paris [a famous restaurant on Boulevard St. Germain, it was frequented by Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir]!

The reviewer adds:

The subtitle of the book is "Chasing Nazi Criminals." Kovacs had been tasked by the Russians to report to them on the other prisoners if he succeeded in hearing confessions about their Nazi past. In the Foreign Legion, Kovacs signed up to hunt the Nazis: he had to bring the legionaries closer to a list given to him by an organization whose aim was to track down hidden Nazis. In his labor camp in the USSR, all the prisoners died except a handful (120 out of 3000 if I remember correctly) died. In Indochina, legionaries died in incredible numbers during the time Kovacs served there. In the USSR, Kovacs himself states that he spent his time writing reports on men who had already died of cold, malnutrition and diseases; in the Foreign Legion, Kovacs crossed off the list of men who died in combat. The justice that Kovacs was looking for strikes me as being totally absent because everyone would die, former Nazis or not.

When I was in graduate school in the 80s at Duke University there was an associate professor emeritus in mechanical engineering named Ernest Elsevier. He was from another era in many ways. He came to the US from Holland as a teenager in the 1930s (I believe by himself). He never had a PhD, but had great experience as a working engineer, very unusual then and more so today. He was loved by the undergraduates and often was very helpful in finding them jobs.

I never had him in a class, nonetheless we became friends. One day I spent the afternoon with him at his cottage on a small lake (or a pond, I don't remember) to go "fishing." I put fishing in quotes because we had gear and bait, we even threw our lines in the water. But for a couple of hours I didn't bother to bait the hook, I just listened and drank beer as for the only time he told me about his experiences in World War II. This was very rare, more than 40 years after the events he was still emotional about them. He served in the Navy as an aviation chief's machinist mate on the USS Enterprise for the full length of the US conflict with Japan.

Enterprise participated in more major actions of the war against Japan than any other United States ship. These actions included the attack on Pearl Harbor - 18 Douglas SBD Dauntless dive bombers of her air group arrived over the harbor during the attack; seven were shot down with eight airmen killed and two wounded, making her the only American aircraft carrier with men at Pearl Harbor during the attack and the first to sustain casualties during the Pacific War 3 - the Battle of Midway, the Battle of the Eastern Solomons, the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands, various other air-sea engagements during the Guadalcanal Campaign, the Battle of the Philippine Sea, and the Battle of Leyte Gulf. Enterprise earned 20 battle stars, the most for any U.S. warship in World War II, and was the most decorated U.S. ship of World War II. She was also the first American ship to sink a full-sized enemy warship after the Pacific War had been declared when her aircraft sank the Japanese submarine I-70 on 10 December 1941. 4 On three occasions during the war, the Japanese announced that she had been sunk in battle, inspiring her nickname "The Grey Ghost". By the end of the war, her planes and guns had downed 911 enemy planes, sunk 71 ships, and damaged or destroyed 192 more. 5 en.wikipedia.org

Ernie had an extended stay on Guadalcanal, where he saw combat and was decorated for valor. Of all the hair razing experiences he had, what made him the most upset had to do with a clever mechanical mechanism. That is, fighter aircraft used a synchronizer to fire bullets through propeller gaps without hitting the blades. This mechanism used gears and linkages to connect the machine gun and propeller shaft to ensure perfectly timed firing. As pilots returned to the Enterprise they were instructed to empty any ammunition in the gun because the flight crew, Ernie's crew, were required to turn the propeller into a locked position. If the gun were loaded it would fire. More than one of his men had their heads blown off due to this negligence.

After learning stories like these I cannot take today's discourse seriously.

Epilogue

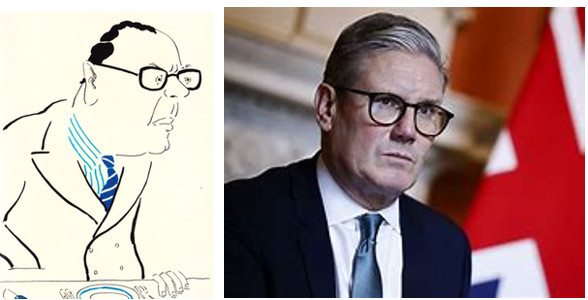

Life Imitates Art: Starmer is Widmerpool

Kenneth Widmerpool, depicted by Mark Boxer on the cover of At Lady Molly's, Fontana 1977 and Sir Keir Starmer today.

One Of the notable characters in Anthony Powell's novel sequence A Dance to the Music of Time, a 12-volume account of upper-class and bohemian life in Britain between 1920 and 1970, is called Kenneth Widmerpool - Wikipedia. You can read about his character in some detail in the Wikipedia article. My short summation is that Widmerpool is a pompous boob with a will to power.

Postscript

This short vignette (a diary entry) from Koestler is so out of character from what we think we know about the war that I thought it would be interesting to readers.

Walking across Navarrenx bridge, suddenly heard my name called-the real one. It was hunch-backed Dr. Pollak; told him for Heaven's sake to shut up, but couldn't get rid of him. Told me he had wondered all the time how I had managed to get out of the Buffalo Camp. He had been sent a few days later to a camp in Brittany; when Germans advanced, the commandant and his staff disappeared over-night; the internees scattered in all directions. Pollak and a group of other old men, all over fifty, mainly Jews, set out and followed the road southward. And on the second day ran into a German column. The German C.O. asked what sort of funny procession they were; they had to explain. C.O. said: 'Don't be scared; we in the Reichswehr are soldiers and don't care about race; camp here, be all of you at the Mairie of M. (nearby village) at five p.m., and I'll see what I can do for you; but five p.m. sharp, mind.' There were about sixty of them, old Jews, émigrés, scared to death, but disciplined Germans: at 5 p.m. they were at the Mairie of M., all complete. Waited quarter of an hour in the midst of astonished German soldiers staring at them, but were not molested; then C.O. turned up, said he had requisitioned a lorry with a French driver, who would take them to unoccupied territory; and so it happened.