By Ron Unz

May 6, 2025

Last week I published a long article exploring the history of Sen. Joseph McCarthy of Wisconsin, whose anti-Communist crusade dominated our politics of the early 1950s. His activities gave rise to "McCarthyism" as a term of abuse and despite the passage of three generations, that expression still seems so widely used today that it has its own 14,000 word Wikipedia article.

In February 1950 McCarthy received huge media attention when he began giving public speeches denouncing the alleged dangers our country faced from the subversive activities of Communists and Soviet agents. Based upon my mainstream history textbooks and the media coverage I'd absorbed, I'd always regarded those claims as wildly exaggerated, so I'd been greatly surprised to gradually discover that the domestic threat of Soviet Communist agents had once been at least as severe as McCarthy alleged.

However, although I became convinced that the menace of Communist infiltration had been very real, I still regarded the senator's own behavior as erratic, with McCarthy prone to making wild accusations. As I wrote a dozen years ago:

In mid-March, the Wall Street Journal carried a long discussion of the origins of the Bretton Woods system, the international financial framework that governed the Western world for decades after World War II. A photo showed the two individuals who negotiated that agreement. Britain was represented by John Maynard Keynes, a towering economic figure of that era. America's representative was Harry Dexter White, assistant secretary of the Treasury and long a central architect of American economic policy, given that his nominal superior, Secretary Henry Morgenthau Jr., was a gentleman farmer with no background in finance. White was also a Communist agent.

Such a situation was hardly unique in American government during the 1930s and 1940s. For example, when a dying Franklin Roosevelt negotiated the outlines of postwar Europe with Joseph Stalin at the 1945 Yalta summit, one of his important advisors was Alger Hiss, a State Department official whose primary loyalty was to the Soviet side. Over the last 20 years, John Earl Haynes, Harvey Klehr, and other scholars have conclusively established that many dozens or even hundreds of Soviet agents once honeycombed the key policy staffs and nuclear research facilities of our federal government, constituting a total presence perhaps approaching the scale suggested by Sen. Joseph McCarthy, whose often unsubstantiated charges tended to damage the credibility of his position.

Some years later I'd read Blacklisted by History, a ringing 2007 defense of McCarthy and his activities by M. Stanton Evans, and last month I did the same with most of the other major books in the pro-McCarthy camp. These included Arthur Herman's widely praised 1999 biography Joseph McCarthy, Ann Coulter's 2003 bestseller Treason, the famous 1954 work McCarthy and His Enemies by William F. Buckley Jr. and L. Brent Bozell, and Buckley's much later 1999 novel The Redhunter, a lightly fictionalized account of the Wisconsin senator's career. To provide some balance, I also reread Richard Rovere's short but highly influential 1959 work Senator Joe McCarthy, providing an account quite hostile to the senator.

With the exception of the Rovere book, all these other works had been written by McCarthy's strongest defenders, but based upon the factual information they provided, my verdict of a dozen years ago was fully confirmed. McCarthy was right that America had faced a great threat from Soviet Communist subversion, but he was frequently wrong about almost everything else.

McCarthy often made wild, unsubstantiated accusations, and he was just as dishonest and careless with facts as his mainstream media critics had always claimed. So although he was hugely successful for several years, he ultimately did enormous damage to his own cause. Moreover, he was very much of a latecomer to the Communism issue and quite possibly merely an opportunist. So he became a public figure who permanently tainted the important work already done by his far more scrupulous and competent political allies.

The widely televised Army-McCarthy Hearings of 1954 destroyed his credibility, and a few months later he was censured by an overwhelming vote of his fellow senators. After his political eclipse, he gradually drank himself to death over the next couple of years.

By the late 1950s, the self-destructive nature of McCarthy's efforts were so widely recognized that they had become a theme of popular fiction. For example, Richard Condon published his Cold War thriller The Manchurian Candidate in 1959 and it was soon made into a famous movie of the same title. This work portrayed the extremely nefarious plots of Communist agents to seize control of our country, but ironically enough, the McCarthy-like political character was eventually revealed to be a Communist dupe, manipulated by our foreign enemies into destroying our society and its freedoms while capturing our government for the Communist conspirators who secretly controlled him.

- American Pravda

- Ron Unz • The Unz Review • April 28, 2025 • 12,700 Words

Towards the beginning of my long article I described how the 1990s declassification of the Venona Decrypts fully confirmed the enormous influence that agents of Soviet Communism had gained over our federal government during the 1930s and 1940s. By the late 1940s, the discovery of so many very high-ranking Soviet operatives such as Alger Hiss and Harry Dexter White easily explained the huge attention that McCarthy attracted when he launched his anti-Communist crusade with a public speech in February 1950, and the arrest of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg later that same year for nuclear weapons espionage seemed to further boost the credibility of his claims. So although McCarthy's accusations were often bombastic and unsubstantiated, they resonated deeply with a fearful public grown suspicious that our elected officials were concealing the true extent of ongoing Communist subversion.

The documented existence of all those important Soviet agents was obviously the proximal factor behind the widespread popular support that McCarthy's political crusade quickly attracted. But I think that there were also much deeper political roots to McCarthyism, roots that have almost always been ignored in our histories of that era, whether these were written by the senator's many mainstream critics or by his small handful of committed defenders. This strange silence seems due to the controversial nature of that prior history, but an important clue to that hidden backstory may be found in an influential book from that era.

In 1955 Daniel Bell published The New American Right, a collection of essays by leading mainstream American academics, and in 1963 he reissued that same work in much expanded form as The Radical Right. McCarthyism was a major part of the analysis and the last two essays by sociologist Seymour Martin Lipset totaled more than 140 pages with both of these focused upon that subject. Lipset demonstrated that the political campaign of the Wisconsin senator shared many of its ideological roots and much of its social base with the earlier 1930s movement of Father Charles Coughlin, a hugely popular anti-Communist radio priest from neighboring Michigan.

Launched in the late 1920s, Coughlin's syndicated weekly radio show eventually became political and grew tremendously popular. At his 1930s peak Coughlin had amassed an enormous national audience estimated at 30 million regular listeners, amounting to roughly one-quarter of the entire American population, probably making him the world's most influential broadcaster. By 1934 the priest was receiving over 10,000 letters of support each day, considerably more than President Franklin Roosevelt or anyone else.

Coughlin began as a strong early supporter of FDR and his New Deal reforms, coining the popular phrases "Roosevelt or Ruin" and "The New Deal is Christ's Deal." But he gradually became disillusioned with FDR and his policies, viewing them as insufficiently bold and far too beholden to Wall Street financial interests. So Coughlin instead began encouraging the political ambitions of Sen. Huey Long of Louisiana, a populist figure who planned to challenge Roosevelt for reelection in 1936, running on a radical platform of "Share the Wealth."

The twin stories of Coughlin and Long and their complex relationship are told in Voices of Protest, an award-winning 1982 book by the distinguished historian Alan Brinkley, who suggested that such a complementary Long-Coughlin political partnership might have given Roosevelt a very difficult race in 1936. But those plans suddenly collapsed in September 1935 when Long was assassinated by a crazed lone gunman, who himself was immediately shot dead. That fortuitous event allowed FDR to win a huge reelection landslide the following year against a weak Republican opponent whose traditional conservative policies offered little popular appeal.

Over the years that followed, Coughlin grew increasingly critical of Jews and Jewish influence, given their hugely disproportionate role as Wall Street bankers, whose activities he regarded as so damaging to the interests of the ordinary American workers whom he championed. In March 1936 he began publishing a weekly political newspaper called Social Justice and it eventually reached a peak circulation of about a million subscribers in the late 1930s, making it one of the most widely read publications in America, having more than ten times the combined circulation of the Nation and the New Republic, the leading liberal weeklies. The complete archives of Social Justice are conveniently available on this website.

Coughlin had always been hostile to Communism, and after the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in July 1936, he began strongly supporting the anti-Communist Nationalist forces, who were also backed by Hitler and Mussolini. Meanwhile, Jewish groups overwhelmingly supported the opposing Loyalist side, heavily backed both by foreign Communists and by Stalin's Soviet Union. This further increased Coughlin's suspicion of Jews.

During this same period, Jewish groups and most of the American mainstream media began harshly condemning Nazi Germany for the persecution of its tiny 1% Jewish minority, and these public attacks reached a crescendo after dozens of Jews were killed in the November 1938 Kristallnacht riots, probably orchestrated by some Nazi leaders.

But Coughlin claimed that Jewish bankers had played a crucial role in the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution that brought Soviet Communism to power, while the very heavily Jewish regime thereby established had been responsible for the deaths of many millions of Christians, easily explaining the Nazi hostility toward Jews and their influence. Coughlin was naturally outraged that our media focused so much of its attention upon the dozens of Jewish deaths at the hands of German Nazis rather than the millions of Christian deaths at the hands of Bolshevik Jews.

These sorts of matters have largely been excluded from our more recent mainstream historical narratives, but they widely circulated at the time. Although I neglected to mention Coughlin I discussed some of these controversial issues in one of my earliest American Pravda articles, published in 2018:

- American Pravda

- Ron Unz • The Unz Review • July 23, 2018 • 7,000 Words

In 1938 Coughlin established a new anti-Communist political organization called the Christian Front, and according to Wikipedia it soon attracted several thousand members, mostly Irish-American men in New York City and other East Coast urban centers. Around that same time, Coughlin was regularly vilified as a fascist sympathizer and the Roosevelt Administration began making efforts to remove him from the airwaves. These efforts intensified after World War II broke out in September 1939 and Coughlin become a leading opponent of American intervention in that military conflict.

In January 1940, the FBI raided the Brooklyn headquarters of the Christian Front and arrested 17 men on charges of plotting to overthrow the U.S. government. But although one defendant committed suicide, the trials of all the others ended in acquittals or hung juries, thus humiliating the federal prosecutors.

But pressure continued and by September 1940 Coughlin was forced to end his radio broadcasts. Then in April 1942 the Espionage Act of 1917 was invoked to ban his Social Justice newspaper from the mails, effectively eliminating nearly all his national media influence. Thus, government action had been used to silence the voice of America's leading broadcaster and also ban the distribution of one of our largest national newspapers, actions vastly more serious than anything done during the anti-Communist domestic campaigns of the Korean War era a decade later.

This extreme crackdown on Coughlin continued as FDR's Attorney General Francis Biddle soon convened a federal grand jury to indict him and his publication on charges of sedition. Biddle then worked out a deal with Coughlin's ecclesiastical superior Archbishop Edward Mooney, promising that the U.S. Justice Department would drop its prosecution of the priest if he closed Social Justice and permanently ceased all his political activities. With Mooney threatening to suspend his ministry, Coughlin agreed to those severe terms. Although he remained the pastor of his local church and lived until 1979, his political and media activities had come to a permanent end.

With Coughlin no longer having a media platform to publicly defend himself, his bitter enemies were able to construct an entirely one-sided narrative of his history and beliefs, and in the aftermath of the American victory in World War II, this official verdict on Coughlin's political career became an extremely hostile one. Decades later, my history textbooks dismissed him in just a sentence or two as a popular antisemitic demagogue with strong fascist tendencies, someone who regularly promoted various implausible conspiratorial theories regarding Jews and Communism.

This huge stigma ensured that when a new generation of rising Republican leaders such as McCarthy and Richard Nixon entered Congress in the first postwar elections of 1946, they apparently never considered identifying themselves with a defeated and demonized figure such as Coughlin, who was already fast becoming a fading memory in elite DC circles. Also, many of these new elected officials had made their names and reputations in World War II, thus rendering Coughlin's fierce opposition to that conflict especially toxic.

And this harsh dismissal of Coughlin grew even stronger over the generations that followed, after all direct memory of his once enormous national influence had been forgotten. All that remained was the very negative image inserted into our history books of a failed, antisemitic political demagogue who had supported our Axis enemies.

Given these realities, it's hardly surprising that McCarthy and his political allies did everything they could to disassociate themselves from Coughlin, and exactly the same was true of all the later conservative writers who attempted to defend or rehabilitate the Wisconsin senator. Coughlin's name barely appeared in any of the books produced by those latter pro-McCarthy authors, only perhaps very briefly mentioned as a long discredited figure whom liberals sometimes falsely included in their defamatory attacks against McCarthy.

But although McCarthy and his camp carefully avoided Coughlin, I think that the fate of that latter figure may nonetheless have loomed very large among many of the senator's ordinary rank-and-file supporters.

Consider that McCarthy's political crusade against Communism began less than a decade after Coughlin had been forcibly removed from public life, and many millions of the priest's followers must have still vividly remembered how the government had politically purged and silenced the man whom they had once so greatly admired.

FDR's governmental crackdown on Coughlin and his anti-Communist organization seemed far more severe and extreme than anything McCarthy or most of his allies ever later advocated against American Communists, let alone those policies that were actually implemented.

Moreover, Coughlin and his followers seem to have been patriotic individuals totally loyal to their own country and having no significant ties to a foreign power, a situation entirely different from that of American Communists or their party. So surely Coughlin's millions of erstwhile supporters believed that if the U.S. government could ban his media outlets, threaten to prosecute him and his followers, and destroy his organization, it was hardly unreasonable that somewhat similar steps should be taken against American Communists, who obviously served the cause of our great foreign adversary.

Given these facts, I think that the close connection between the political movements of Coughlin and McCarthy suggested by Lipset and the other academics featured in Bell's collection of essays was probably correct and can actually be taken much further. This relates to a far broader historical omission I have noticed in the overwhelming majority of the accounts describing the rise of McCarthy and his political movement.

As I have mentioned, that Republican Wisconsin Senator of Irish and German ancestry launched his efforts in 1950, and his anti-Communist crusade soon became a popular political vehicle for attacking the careers of leftists and liberals. These often involved attempts to get such individuals purged from their media perches or academic positions by accusations, true or otherwise, of Communist sympathies or disloyalty to America.

Yet these accounts only very rarely hinted that only a decade earlier, almost exactly the same situation had occurred but with the roles of ideological victim and victimizer entirely reversed. Thus, many of the individuals and organizations supporting McCarthyism were probably seeking retribution because they themselves and their allies had suffered from much the same sorts of attacks around 1940, with many of the victims being similarly demonized and purged from the media and public life. Coughlin was hardly alone.

But the story of those American ideological purges has been almost entirely excluded from our standard history books, while few modern day conservatives, even those defending McCarthy, evince any sympathy for most of those earlier victims.

Of all the pro-McCarthy books that I read, only Herman briefly alluded to those facts. For example, the Coulter book never even mentioned Coughlin's name, nor did either of Buckley's books. Therefore, I doubt whether even five in one hundred of those reading the various books defending McCarthy are even aware of that important backstory to McCarthy's political movement.

Although I had ignored the important case of Coughlin, back in 2018 I'd published an article describing that sweeping but long forgotten 1940 ideological purge of so many important academics and journalists carried out by FDR and his liberal allies. As I wrote:

Take the case of John T. Flynn, probably unknown today to all but one American in a hundred, if even that. Given my much broader ideological explorations, I had sometimes seen him hailed as an important figure in the Old Right, a founder of the America First Committee, and someone friendly to both Sen. Joseph McCarthy and the John Birch Society, though falsely smeared by his opponents as a proto-fascist or Nazi-sympathizer. This sort of description seemed to form a consistent if somewhat disputed picture in my mind.So imagine my surprise at discovering that throughout the 1930s he had been one of the single most influential liberal voices in American society, a writer on economics and politics whose status may have roughly approximated that of Paul Krugman, though with a strong muck-raking tinge. His weekly column in The New Republic allowed him to serve as a lodestar for America's progressive elites, while his regular appearances in Colliers, an illustrated mass circulation weekly reaching many millions of Americans, provided him a platform comparable to that of a major television personality in the later heyday of network TV.

To some extent, Flynn's prominence may be objectively quantified. A few years ago, I happened to mention his name to a well-read and committed liberal born in the 1930s, and she unsurprisingly drew a complete blank, but wondered if he might have been a little like Walter Lippmann, the very famous columnist of that era. When I checked, I saw that across the hundreds of periodicals in my archiving system, there were just 23 articles by Lippmann from the 1930s but fully 489 by Flynn.

Much of Flynn's early prominence came from his important role in the 1932 Senate Pecora Commission, which had pilloried the grandees of Wall Street for the 1929 stock market collapse, and whose recommendations ultimately led to the creation of the Securities and Exchange Commission and other important financial reforms. Following an impressive career in newspaper journalism, he had moved over to The New Republic as a weekly columnist in 1930. Although initially sympathetic to Franklin Roosevelt's goals, he soon became skeptical about the effectiveness of his methods, noting the sluggish expansion of public works projects and wondering whether the vaunted NRA was actually more beneficial to big business owners than to ordinary workers.

As the years went by, his criticism of the Roosevelt Administration turned harsher on economic and eventually foreign policy grounds, and he incurred its enormous hostility as a consequence. Roosevelt began sending personal letters to leading editors demanding that Flynn be barred from any prominent American print outlet, and perhaps as a consequence he lost his longstanding New Republic column immediately following FDR's 1940 reelection, and his name disappeared from mainstream periodicals.

We should not be entirely surprised that during the early 1950s Flynn became known as a strong supporter of McCarthy.

Although Flynn was perhaps the most prominent intellectual figure to disappear from public visibility around that time, he was hardly alone. As I began to explore the aggregate contents of so many of the publications that had influenced our ideas since the 19th century, I detected a significant discontinuity centered around a particular period. Quite a number of individuals—Left, Right, and Center—who had been so prominently featured until that point suddenly disappeared, in many cases permanently, near the start of the Great American Purge of the 1940s.I sometimes imagined myself a little like an earnest young Soviet researcher of the 1970s who began digging into the musty files of long-forgotten Kremlin archives and made some stunning discoveries. Trotsky was apparently not the notorious Nazi spy and traitor portrayed in all the textbooks, but instead had been the right-hand man of the sainted Lenin himself during the glorious days of the great Bolshevik Revolution, and for some years afterward had remained in the topmost ranks of the Party elite. And who were these other figures—Zinoviev, Kamenev, Bukharin, Rykov—who also spent those early years at the very top of the Communist hierarchy? In history courses, they had barely rated a few mentions, as minor Capitalist agents who were quickly unmasked and paid for their treachery with their lives. How could the great Lenin, father of the Revolution, have been such an idiot to have surrounded himself almost exclusively with traitors and spies?

But unlike their Stalinist analogs from a couple of years earlier, the American victims who disappeared around 1940 were neither shot nor Gulaged, but merely excluded from the mainstream media that defines our reality, thereby being blotted out from our memory so that future generations gradually forgot that they had ever lived.

One such victim was historian Harry Elmer Barnes, a figure almost unknown to me, but in his day an academic of great influence and stature.

Imagine my shock at later discovering that Barnes had actually been one of the most frequent early contributors to Foreign Affairs, serving as a primary book reviewer for that venerable publication from its 1922 founding onward, while his stature as one of America's premier liberal academics was indicated by his scores of appearances in The Nation and The New Republic throughout that decade. Indeed, he is credited with having played a central role in "revising" the history of the First World War so as to remove the cartoonish picture of unspeakable German wickedness left behind as a legacy of the dishonest wartime propaganda produced by the opposing British and American governments. And his professional stature was demonstrated by his thirty-five or more books, many of them influential academic volumes, along with his numerous articles in The American Historical Review, Political Science Quarterly, and other leading journals.A few years ago I happened to mention Barnes to an eminent American academic scholar whose general focus in political science and foreign policy was quite similar, and yet the name meant nothing. By the end of the 1930s, Barnes had become a leading critic of America's proposed involvement in World War II, and was permanently "disappeared" as a consequence, barred from all mainstream media outlets, while a major newspaper chain was heavily pressured into abruptly terminating his long-running syndicated national column in May 1940.

In many respects, Barnes' situation typified those who fell in the purge. Although many powerful critics of FDR's presidency had suffered from a considerable amount of government investigation and IRS harassment throughout the 1930s, America's movement towards involvement in a new world war seems to have been the central factor behind a wider purge of public intellectuals and other political opponents. The combined influence of the pro-British Eastern Establishment together with powerful Jewish groups was deployed to clear the media of opposing figures, and after the Germans broke the Hitler-Stalin Pact by attacking the USSR in June 1941, Communists and other leftists also joined this effort. Polls seem to have shown that as much as 80% of the American public was opposed to such military involvement, so any prominent political or media figure giving voice to that popular super-majority needed to be silenced.

Over a dozen years after his disappearance from our national media, Barnes managed to publish Perpetual War for Perpetual Peace, a lengthy collection of essays by scholars and other experts discussing the circumstances surrounding America's entrance into World War II, and have it produced and distributed by a small printer in Idaho. His own contribution was a 30,000 word essay entitled "Revisionism and the Historical Blackout" and discussed the tremendous obstacles faced by the dissident thinkers of that period.

The book itself was dedicated to the memory of his friend, historian Charles A. Beard. Since the early years of the 20th century, Beard had ranked as an intellectual figure of the greatest stature and influence, co-founder of The New School in New York and serving terms as president of both The American Historical Association and The American Political Science Association. As a leading supporter of the New Deal economic policies, he was overwhelmingly lauded for his views.

Yet once he turned against Roosevelt's bellicose foreign policy, publishers shut their doors to him, and only his personal friendship with the head of the Yale University Press allowed his critical 1948 volume President Roosevelt and the Coming of the War, 1941 to even appear in print. Beard's stellar reputation seems to have begun a rapid decline from that point onward, so that by 1968 historian Richard Hofstadter could write: "Today Beard's reputation stands like an imposing ruin in the landscape of American historiography. What was once the grandest house in the province is now a ravaged survival". Indeed, Beard's once-dominant "economic interpretation of history" might these days almost be dismissed as promoting "dangerous conspiracy theories," and I suspect few non-historians have even heard of him.

Another major contributor to the Barnes volume was William Henry Chamberlin, who for decades had been ranked among America's leading foreign policy journalists, with more than 15 books to his credit, most of them widely and favorably reviewed. Yet America's Second Crusade, his critical 1950 analysis of America's entry into World War II, failed to find a mainstream publisher, and when it did appear was widely ignored by reviewers. Prior to its publication, his byline had regularly run in our most influential national magazines such as The Atlantic Monthly and Harpers. But afterward, his writing was almost entirely confined to small circulation newsletters and periodicals, appealing to narrow conservative or libertarian audiences.

- American Pravda: Our Great Purge of the 1940s

- Ron Unz • The Unz Review • June 11, 2018 • 5,500 Words

A half-century ago, early in his long and distinguished career, noted historian Ronald Radosh published Prophets on the Right, a 1975 book providing sympathetic portrayals of several of these individuals, including two chapters each on John T. Flynn, Charles A. Beard, and Oswald Garrison Villard, describing the political forces that FDR deployed to suppress each of them around 1940.

Some of the academic scholars and journalists purged around 1940 were of vastly greater stature than anyone whose career was destroyed by McCarthy or any of the other anti-Communist crusaders of that postwar era. Moreover, unlike nearly all those later victims, none of these earlier figures had the slightest trace of any foreign connection or hint of disloyalty. Instead, they were all destroyed merely for their sincere disagreement with Roosevelt's policies.

But by far the most prominent victim of that sweeping ideological purge of the early 1940s was famed aviator Charles A. Lindbergh, a towering public figure who for nearly two decades had been widely regarded as America's greatest national hero.

Just as McCarthy regularly smeared his targets as Communists or Communist sympathizers, often using such unfair tactics to successfully destroy their reputations, during 1940 and 1941 Lindbergh was viciously attacked as a Nazi or Nazi sympathizer for his sincere opposition to our involvement in World War II. As early as May 1940, President Roosevelt began making these accusations in his private conversations and correspondence with leading members of his Cabinet, thereby ensuring that such claims got into wider circulation:

On May 20, the day after Lindbergh's air defense speech, the President was having lunch with his treasury secretary, Henry Morgenthau. After a brief discussion of this latest radio address, the President put down his fork, turned to his most trusted Cabinet official and declared, "If I should die tomorrow, I want you to know this. I am absolutely convinced that Lindbergh is a Nazi.""When I read Lindbergh's speech, I felt that it could not have been better put if it had been written by Goebbels himself," the President wrote to Henry Stimson, a Republication politician whom Roosevelt had recently asked to serve as his new secretary of war. "What a pity that this youngster has completely abandoned his belief in our form of government and has accepted Nazi methods because apparently they are efficient."

FDR's private statements were increasingly echoed by large portions of the mainstream media, and by July 1941 Interior Secretary Harold Ickes was publicly attacking Lindbergh along those same lines. As I discussed in a long article earlier this year, that massive campaign of public vilification reached a crescendo after Lindbergh's controversial speech in September 1941:

Alarmed by their growing fear that America might be drawn into another world war without voters having had any say in the matter, a group of Yale Law students launched an anti-interventionist political organization that they named "The America First Committee," and it quickly grew to 800,000 members, becoming the largest grass-roots political organization in our national history. Numerous prominent public figures joined or supported it, with the chairman of Sears, Roebuck serving as its head, and its youthful members included future presidents John F. Kennedy and Gerald Ford as well as other notables such as Gore Vidal, Potter Stewart, and Sargent Schriver. Flynn served as chairman of the New York City chapter, and the organization's leading public spokesman was famed aviator Charles Lindbergh, who for decades had probably ranked as America's greatest national hero.Throughout 1941, enormous crowds across the country attended anti-war rallies addressed by Lindbergh and the other leaders, with many millions more listening to the radio broadcasts of the events. Mahl shows that British agents and their American supporters meanwhile continued their covert operations to counter this effort by organizing various political front-groups advocating American military involvement, and employing fair means or foul to neutralize their political opponents. Jewish individuals and organizations seem to have played an enormously disproportionate role in that effort.

At the same time, the Roosevelt Administration escalated its undeclared war against German submarines and other naval forces in the Atlantic, unsuccessfully seeking to provoke an incident that might stampede the country into war. FDR also promoted the most bizarre and ridiculous propaganda inventions aimed at terrifying naive Americans, such as claiming to have proof that the Germans—who possessed no large surface navy and were completely stymied by the English Channel—had formulated concrete plans to leap across two thousand miles of the Atlantic Ocean and seize control of Latin America. British agents supplied some of the crude forgeries he cited as evidence.

These facts, now firmly established by decades of scholarship, provide some necessary context to Lindbergh's famously controversial speech at an America First rally in September 1941. At that event, he charged that three groups in particular were "pressing this country toward war: the British, the Jewish, and the Roosevelt Administration," and thereby unleashed an enormous firestorm of media attacks and denunciations, including widespread accusations of anti-Semitism and Nazi sympathies. Given the realities of the political situation, Lindbergh's statement constituted a perfect illustration of Michael Kinsley's famous quip that "a gaffe is when a politician tells the truth - some obvious truth he isn't supposed to say." But as a consequence, Lindbergh's once-heroic reputation suffered enormous and permanent damage, with the campaign of vilification echoing for the remaining three decades of his life, and even well beyond. Although he was not entirely purged from public life, his standing was certainly never even remotely the same.

- American Pravda: Charles A. Lindbergh and the America First Movement

- Ron Unz • The Unz Review • February 10, 2025 • 15,600 Words

McCarthy's harsh anti-Communist accusations ended the careers of numerous Democratic senators and congressmen during the 1952 and 1954 elections, but just a few years earlier very similar campaigns of vilification had done the same with prominent political allies of Lindbergh. Sen. Gerald Nye of North Dakota fell in 1944 and Sen. Burton K. Wheeler of Montana lost his seat in 1946. Although the latter had spent his entire career as a strongly progressive Democrat, he was denounced as a fascist-sympathizer in campaign materials distributed by political organizations aligned with the Communist Party, and defeated for renomination in his own primary.

Probably the most infamous example of outrageous McCarthyite election methods came in 1952 when the Wisconsin senator managed to unseat Sen. Millard Tydings of Maryland, a Democratic grandee who had seemed unbeatable after twenty-four years in office.

In that campaign, McCarthy's close political allies widely distributed a doctored photographic montage appearing to show Tydings in friendly conversation with Earl Browder, thus suggesting that the reactionary segregationist Democrat was a close comrade-in-arms with America's top Communist leader, and this may have confused enough gullible voters to defeat the incumbent. That notorious incident has long been a staple of anti-McCarthy narratives, but probably only a sliver of those readers are aware that such dishonest tactics merely echoed something very similar used to defeat a top Republican a few years earlier.

After twenty-four years in office, Rep. Hamilton Fish of upstate New York had become one of the most senior Republicans in the House, serving as the ranking member on the Foreign Relations Committee, and a particular thorn in the side of the president since he was FDR's own Representative. But in 1944 that entrenched scion of a local political dynasty was finally defeated for reelection by a scurrilous advertising campaign that falsely depicted him consorting with American Nazi leader Fritz Kuhn. Fish later claimed that the huge wave of funding responsible for his political destruction had come from New York City Communists.

Other important Republicans narrowly avoided a similar fate. As the eldest son of a former American president and Supreme Court justice, Sen. Robert Taft of Ohio became known as "Mr. Republican," leading his party in the Senate and nearly being nominated for president in 1940, 1948, and 1952. But he was almost defeated for reelection in 1944 when a Communist-aligned political committee widely distributed a pamphlet accusing him of being a friend to Hitler and Hirohito.

Indeed, a 1943 national bestseller entitled Under Cover by the pseudonymous John Roy Carlson suggested that numerous prominent Republicans were fascist supporters of Hitler, and that book received enormous coverage in mainstream media outlets, heavily amplified by FDR's supporters and allies.

These last two of examples were very briefly mentioned in Herman's excellent book on McCarthy, which devoted a couple of pages to such stories from the 1940s. Just as the public speeches of the Wisconsin senator and the various books and pamphlets produced by his political allies had destroyed their political enemies by regularly—and falsely—accusing them of being "soft on Communism," a decade or so earlier exactly the same sort of false claims of Nazi sympathies had been made in the other direction, often by Communist-oriented groups and individuals.

However, the Herman book was very much the exception in raising those points. Despite such obvious and consistent parallels between these two political campaigns of slander and the mirror-image ideological purges they successfully achieved just a few years apart, attention has only very rarely been given to this issue in accounts of McCarthy and his rise to power, whether in our standard textbooks or in works devoted to the career of the Wisconsin senator.

The Evans book on McCarthy ran 700 pages and totally ignored all of this, and the same was true of the books by Rovere, Coulter, or Buckley and Bozell. And although I haven't yet had a chance to read it, Clay Risen's Red Scare, published just a few weeks ago, seems equally silent on this crucial history that inspired the McCarthyism of the early 1950s.

This historical background was obviously so important that Herman probably should have allocated a full chapter to the topic rather than merely a couple of pages. But that couple of pages was still a couple of pages more than I found in almost any other book on McCarthy's political rise.

Patriarch Joseph Kennedy was a strong supporter of the failed America First Committee that sought to prevent our involvement in World War II, as was his youthful son John F. Kennedy, and a few years later both became enthusiastic supporters of McCarthy. America First had been strongest among Midwesterners as well as Irish-Americans and German-Americans, and these groups constituted much of McCarthy's political base, while some of the strongest opposition to America First came from the East Coast WASP elites, whom McCarthy later routinely vilified. Yet these obvious aspects of the McCarthy movement are almost never discussed.

As an absurd analogy, suppose that all our standard histories of World War II always carefully omitted any mention of World War I, leading puzzled young readers to wonder why the numbering of our world wars had begun with "Two." In some respects, such a totally ridiculous situation seems quite similar to the standard portrayal of the McCarthyite crackdown on Communist and pro-Communist organizations and individuals. Much of McCarthyism was probably political payback, plain and simple.

For the last three generations, liberal and mainstream critics of the anti-Communist investigations of the late 1940s and 1950s have regularly condemned on civil libertarian grounds the political infrastructure successfully used to persecute those victims, notably including the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) and the Smith Act, and much of that criticism may have merit.

However, it is usually forgotten that HUAC had originally been established in 1938 with strong liberal and Democratic support because its primary targets were right-wing anti-Communists such as Coughlin and his Christian Front. But after that same House Committee later turned its attention to American Communists, its former supporters fiercely denounced and sought to eliminate it, hypocritically concealing that earlier history.

Similarly, the Smith Act established criminal penalties for advocating the overthrow of the U.S. government and was used as the legal vehicle for a couple of hundred indictments until finally struck down as unconstitutional by a series of Supreme Court decisions in 1957. Beginning in 1949 many dozens of Communist Party members were indicted and prosecuted merely for their political beliefs under that notorious law, some of them receiving prison sentences, with this legal attack on our Constitutional freedoms considered among the most egregious violations of the early Cold War era.

But once again, it is usually forgotten that the Smith Act had actually been enacted in 1940 with overwhelming liberal support because conservatives and right-wingers were considered its primary intended targets. Indeed, according to the Wikipedia page, Roosevelt had even wanted to use that law to prosecute his leading political opponents such as Charles Lindbergh and the publishers of the Chicago Tribune, the New York Daily News, and the Washington Times-Herald, several of America's largest newspapers.

Mainstream media articles and passages in our standard history textbooks frequently describe the "Red Scare" of the early 1950s closely associated with the activities of Sen. Joseph McCarthy. But these accounts almost never mention the preceding "Brown Scare" of the late 1930s and early 1940s. This phrase was coined by historian Leo Ribuffo in his important 1983 book The Old Christian Right, with the author discussing the topic at length in a chapter of that title.

Whereas McCarthy was merely a single senator albeit a highly influential one and possessed no law enforcement powers, Ribuffo explained that during that previous period the entire weight of FDR's federal government and his FBI were deployed to investigate and harass ideological opponents, culminating in the Great Sedition Trial of 1944, the largest such case in American history.

In that legal proceeding, a motley collection of some thirty mostly unconnected right-wing defendants were prosecuted under the Smith Act, essentially accused of criticizing the government, a prosecution undertaken with enthusiastic Communist Party support. With so many different defendants of such varied characteristics and beliefs, few of whom had ever previously been in contact, the trial was exceptionally cumbersome and complex, dragging on for a couple of years until the death of the judge led to a mistrial. At that point, the new Truman Administration finally decided to end the embarrassing spectacle by dismissing all the charges.

One of the most prominent and erudite defendants in that trial had been Harvard-educated Lawrence Dennis, a former diplomat who had resigned his post in disgust over American military intervention in Nicaragua, with his ideological background and political activities discussed in a couple of chapters of the Radosh book.

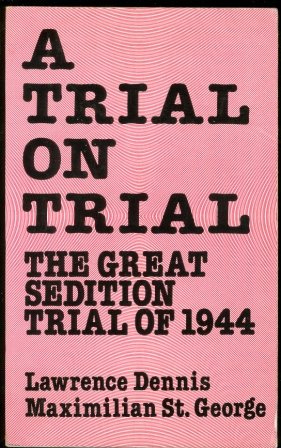

Dennis later became a prominent public intellectual after he published a series of influential articles in the Nation and the New Republic as well as his 1932 book entitled Is Capitalism Doomed? Following the dismissal of the sedition charges against him, he described his experiences during that early 1940s trial in his scathing 1946 book A Trial On Trial. Copies are outrageously priced on Amazon, but it is fortunately also freely available at Archive.org.

Ironically enough, years before anyone had ever heard of McCarthy, Sen. Wheeler had presciently suggested the likely appearance of the political movement eventually named for that Wisconsin politician.

Herman noted that in 1943 Wheeler had predicted to Flynn that there would be just such a future political backlash: "The more internationalists try to smear people now, the more it is going to react against them when this war is over." The author then declared "Wheeler turned out to be correct—and McCarthy was in many ways the instrument of sweet revenge."