Lorenzo Maria Pacini

The contemporary relevance of the principle of non-intervention appears marked by profound ambivalence.

The conceptual origin

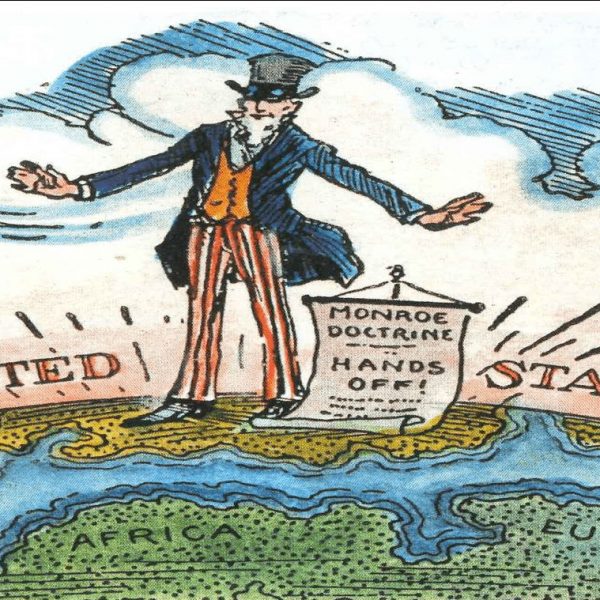

With regard to the conceptual origins of the rule of non-intervention in international law, legal scholarship often traces its foundation to the work of the eighteenth-century Swiss philosopher Emer de Vattel. In The Law of Nations, Vattel argued that when one nation intrudes into the internal affairs of another, it commits an injury. The idea of non-intervention gained greater prominence during the nineteenth century, in response to the hegemonic ambitions of the major European powers of the time-such as Austria, Prussia, and Russia-united in the Holy Alliance. In this context, the Monroe Doctrine-proclaimed in 1823 by U.S. President James Monroe and asserting that any European interference in the Western Hemisphere would be regarded as a hostile act against the United States-is often cited as one of the earliest manifestations of state practice relating to the principle of non-intervention.

However, it was only in the twentieth century that this principle began to be formalized in international legal instruments. It was explicitly enshrined in several treaties concluded among states of the American continent. In particular, Article 8 of the Montevideo Convention on the Rights and Duties of States establishes that no state has the right to intervene in the internal or external affairs of another. This assertion was reaffirmed in Article 1 of the 1936 Additional Protocol to the Montevideo Convention on Non-Intervention, in which the contracting parties declare inadmissible any form of intervention-direct or indirect, for whatever reason-in the internal or external affairs of another state party.

The Monroe Doctrine represents one of the most significant reference points in the history of international relations for understanding the evolution of the principle of non-intervention, despite its intrinsic ambiguity. Proclaimed in 1823 by U.S. President James Monroe, it emerged in a historical context marked by the decline of European colonial empires in the Americas and by fears that the powers of the Holy Alliance might intervene to restore monarchical rule in the newly independent Latin American states. In this sense, the Monroe Doctrine appeared as an assertion of the defense of the political autonomy of the American continent against external interference, implicitly invoking the principle of non-intervention.

In its original formulation, the Monroe Doctrine stated that any European intervention in the affairs of the Western Hemisphere would be considered by the United States a hostile act. This stance seemed to reinforce the idea that each state should be free to determine its own political and institutional arrangements without external interference-a concept closely aligned with the modern notion of sovereignty and the prohibition of intervention in the internal affairs of other states. Yet this apparent adherence to the principle of non-intervention was accompanied by an asymmetric logic: while European interference in the Americas was rejected, the possibility of an active role for the United States in the region was not excluded.

This asymmetry constitutes the primary source of tension between the Monroe Doctrine and the principle of non-intervention as developed in contemporary international law. Throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the doctrine was progressively reinterpreted and expanded, particularly through the so-called Roosevelt Corollary of 1904, which attributed to the United States the right to intervene in the internal affairs of Latin American states in order to prevent interference by extra-hemispheric powers. At this stage, the Monroe Doctrine ceased to function as a tool for defending non-interference and instead became an ideological justification for U.S. interventionism.

From the perspective of international law, the Monroe Doctrine cannot be regarded as a legally binding norm, but rather as a unilateral act of foreign policy. Nevertheless, it has exerted significant influence on state practice and on doctrinal debates concerning non-intervention, especially at the regional level. In Latin America, repeated U.S. interventions contributed reactively to the development of legal instruments explicitly affirming the prohibition of intervention, such as the Montevideo Convention and the Charter of the Organization of American States.

The Charter of the United Nations does not contain a provision expressly regulating the principle of non-intervention in relations among individual states. However, Article 2(7) states that nothing in the Charter authorizes the United Nations to intervene in matters that are essentially within the domestic jurisdiction of any state. A similar provision had already been included in the Covenant of the League of Nations, whose Article 15(8) excluded the possibility of the League making recommendations regarding disputes that, under international law, fell exclusively within domestic jurisdiction. According to some scholars, the replacement of the reference to "international law" with the term "essentially" in the UN Charter was intended to broaden and strengthen the scope of the domestic jurisdiction clause compared to that of the League Covenant.

Although Article 2(7) concerns the actions of the United Nations as an organization rather than the conduct of individual states, it nonetheless provides useful guidance for understanding the operation of the principle of non-intervention, since the concerns underlying its adoption are similar to those supporting that principle. Other provisions of the Charter indirectly reinforce the prohibition of intervention, such as the principle of the "sovereign equality" of member states enshrined in Article 2(1).

Following the adoption of the UN Charter, numerous regional instruments incorporated explicit prohibitions on state-to-state intervention. Articles 15 and 16 of the 1948 Charter of the Organization of American States provide a detailed description of prohibited conduct, banning not only the use of armed force but also any other form of political or economic interference or coercion. Similarly, the 2000 Constitutive Act of the African Union reaffirms the principle of non-interference in the internal affairs of member states, while the 2007 ASEAN Charter requires its members to act in accordance with the principle of non-interference in the internal affairs of other member states.

Accordingly, although the principle of non-intervention is not explicitly articulated in the UN Charter or other universally oriented treaties, many states have committed themselves to respecting it through regional agreements. The fact that these instruments have been ratified by states from different geographic regions strengthens the argument that the prohibition of intervention constitutes a rule of customary international law.

Customary international law is based on two elements: widespread and consistent state practice, and the belief that such practice is legally required (opinio juris). As clarified by the International Law Commission, it is necessary to examine what states actually do in order to determine whether they recognize an obligation or a right to act in a certain way. Both elements are required, and it is generally accepted that verbal conduct, whether written or oral, may also constitute relevant state practice. Moreover, modern custom is often derived from multilateral treaties and declarations adopted in international fora such as the UN General Assembly.

In addition to the multilateral treaties already mentioned, numerous UN General Assembly resolutions provide further support for the customary nature of the rule of non-intervention. Among these, the 1970 Declaration on Friendly Relations occupies a central position. Adopted unanimously, it affirms that the principles of the Charter embodied in the Declaration constitute fundamental principles of international law. Among these principles is the duty not to intervene in matters within the domestic jurisdiction of states. The Declaration defines the prohibition of intervention in detail, encompassing not only armed intervention but also all forms of coercion or interference aimed at undermining a state's political, economic, social, and cultural autonomy, as well as support for subversive or terrorist activities directed at the violent overthrow of another government.

Although the 1970 Declaration represents the most authoritative instrument on the subject, it forms part of a series of preceding and subsequent resolutions. The 1965 Declaration on the Inadmissibility of Intervention in the Domestic Affairs of States, adopted almost unanimously, used very similar language, though it was regarded by some states, including the United States, as merely an expression of political intent. The 1981 Declaration adopted a broader and more detailed approach, but the significant opposition it encountered limited its value as an expression of customary international law.

In its most significant jurisprudence, the International Court of Justice has recognized the central role of the Friendly Relations Declaration in defining the customary scope of the principle of non-intervention. In the Military and Paramilitary Activities in and against Nicaragua case, the Court identified coercion affecting a state's sovereign choices as the defining element of unlawful intervention, affirming that expressions of opinio juris supporting the principle are numerous and readily identifiable. The Court further reiterated that the prohibition of intervention constitutes a customary principle of universal application, while acknowledging that it has frequently been violated in practice.

It may also be noted that during the Cold War, major powers often interfered in the internal affairs of weaker states, revealing a significant gap between the normative content of the principle and the actual behavior of states. The Court nevertheless clarified that the absence of perfect conformity in practice does not undermine the existence of the customary rule, a position reaffirmed in the judgment on Armed Activities on the Territory of the Congo.

Finally, there is broad agreement among scholars and states that the principle of non-intervention also applies to cyber operations, despite frequent violations observed in practice. The Tallinn Manual 2.0-a document that marked a turning point in the interpretation of neutrality and non-intervention-argues that repeated breaches of the prohibition do not affect its legal validity, even though it does not officially reflect state positions. Official statements by numerous states and the final report of the 2015 UN Group of Governmental Experts confirm that states regard the principle of non-intervention as applicable to the use of information and communication technologies, notwithstanding persistent uncertainties regarding its constituent elements and precise scope.

A delicate vulnerability

A combined reading of the historical evolution of the principle of non-intervention and the Monroe Doctrine highlights with particular clarity a structural contradiction that continues to characterize the international order: the tension between the formal universality of legal norms and their selective application by great powers. The principle of non-intervention, which gradually emerged from natural law thought and was later enshrined in customary international law and the jurisprudence of the International Court of Justice, is grounded in the idea of sovereign equality and the right of each state to determine freely its own political, economic, and social order. At least at the normative level, it constitutes one of the pillars of the contemporary international system.

The Monroe Doctrine, proclaimed in 1823, is often portrayed as an early affirmation of this principle insofar as it rejected European interference in the affairs of the Western Hemisphere. Yet a closer historical examination reveals that the doctrine was rapidly transformed by the United States into an instrument of regional dominance. Far from constituting an impartial defense of non-intervention, it ultimately legitimized a specific form of political and economic colonialism in South America, exercised not through direct territorial annexation but through mechanisms of indirect control, diplomatic pressure, selective military interventions, and economic and cultural influence.

In this sense, the Monroe Doctrine functioned as an ideological framework for U.S. soft power in Latin America. By invoking stability, order, and regional security, the United States justified systematic interference in the internal political processes of numerous South American states, supporting governments aligned with its interests, conditioning local economies, and intervening-directly or indirectly-against regimes perceived as hostile. The Roosevelt Corollary represents the most explicit articulation of this logic, attributing to the United States a genuine "right of corrective intervention," in clear contradiction with the principle of non-intervention.

In light of this historical experience, the contemporary relevance of the principle of non-intervention appears marked by profound ambivalence. On the one hand, it is widely recognized today as a customary rule of universal scope, reaffirmed in regional and global legal instruments and extended to new domains such as cyberspace. On the other hand, U.S. practice associated with the Monroe Doctrine demonstrates how non-intervention can be emptied of substance through its instrumental use by hegemonic powers, which invoke it to exclude external rivals while violating it vis-à-vis weaker states.

The Monroe Doctrine therefore not only represents a historical precedent but continues to serve as a critical paradigm for understanding the real limits of the principle of non-intervention. It illustrates how international law, though formally neutral and universalistic, can be bent to hegemonic logics and forms of informal colonialism, rendering non-intervention a central yet persistently vulnerable principle in the contemporary international system.