By A Midwestern Doctor

The Forgotten Side of Medicine

February 18, 2025

Many traditions throughout history have come to view the prenatal period and childbirth as one of the most important moments in a human's life as it sets the stage for all that follows. Unfortunately, much in the same way we desecrate the death process by over-medicalizing it (to the point research has found doctors are less likely to seek end of life care at a medical facility), the same issue also exists with childbirth. Many physicians I know who are familiar with the hospital birthing process chose to skip it and give birth at home (along with many more doctors featured in a 2016 documentary).

Conversely, a minority of childbirths do need advanced medical care, and for those mothers, access to a hospital greatly benefits them, particularly if actions are taken to mitigate the most dangerous aspects of hospital birth. As such, childbirth occupies a similar place as many other medical controversies; neither side of the issue is entirely correct. However, the discussion remains perpetually polarized because advocates on either side will not acknowledge the valid points raised by the other side for fear of weakening their own position. Since I feel strongly about the dangers of hospital birth, it is my hope in this article that I will be able to portray both sides of the issue fairly.

Note: I feel one of the most destructive trends in our society has been the devaluation of motherhood (e.g., when I visited China, it was striking how much more respect and consideration they gave to pregnant women) and children. Beyond new life being necessary for the viability of our society, it often ends up being the most transformative and fulfilling experience in a parent's life. Yet, so much of our societal messaging encourages us to shun that path and put our hearts into other things. In parallel, a general disconnect has been fostered upon this entire process where it is treated as a sterile, lifeless, and mechanistic event we need to be separated from and entrust to someone else-which I believe is the ultimate problem that underlies many of the issues that will be discussed in this article.

The History of Midwifery

A lot of the dysfunctional things that have come to characterize the birthing process (e.g., unnecessary hospital interventions that create complications begetting more hospital interventions) make much more sense once you understand the history behind them and how childbirth was transformed from a natural human life-event to a medical emergency requiring those interventions.

From the start of America, midwives were highly valued in colonial communities, receiving housing, food, land, and salary for their services (particularly since they also served as nurses, herbalists, and veterinarians). Then, during the 1800s, midwives played a key role in the westward expansion, particularly in the Mormon migration to Utah, but by the early 1900s, a variety of social factors (e.g., economic pressure and societal prejudices) caused midwifery's reputation to decline.

Much of this was due to male doctors (who had initially been averse to delivering babies) displacing midwives. This began in the late 1700s when it became fashionable in Europe to have doctors attend deliveries, after which an influential Harvard professor (and its first profession of obstetrics) convinced his American colleagues to enter, for example in 1820 stating:

Women seldom forget a practitioner who has conducted them tenderly and safely through parturition they feel a familiarity with him, a confidence and reliance upon him which is of the most essential mutual advantage.... It is principally on this account that the practice of midwifery becomes desirable to physicians. It is this which ensures to them the permanency and security of all their other business.

Once doctors entered the field of midwifery, it quickly became necessary to justify their "expertise" and a gradual medicalization of childbirth began.

Dr. Joseph DeLee (who later became known as the father of obstetrics), in 1895, opened Chicago's first obstetric clinic, and since it was successful, opened an obstetrics hospital which also trained doctors and nurses and developed lifesaving innovations (e.g., incubators for premature infants) which lowered the childbirth mortality rate.

Simultaneously however, because DeLee observed so many complications and deaths from childbirth, he was of the opinion that natural childbirth was extremely dangerous for both the mother and child, and hence needed to be medicalized. In turn, he spoke actively (e.g., at a 1915 professional meeting) against the use of midwives, arguing they lowered the standards of the profession, and were childbirth to be seen as a more dignified profession, higher fees could be charged, and more doctors would be willing to replace midwives.

Following this (like many zealots), in 1920, he argued that the approaches he had developed for challenging pregnancies (e.g., forceps, episiotomy, toxic anesthetics) should be used for most of them, while other doctors argued these approaches were too aggressive in many of the situations where DeLee advocated for them. However, due to his growing influence in the profession and success in making childbirth a part of the medical curriculum (in part due to how many doctors he trained) by the 1930s, his standardized invasive approaches became increasingly popular, particularly since society had become enamored with advanced technology improving things.

Finally, near the end of his career (in 1933), due to increasing maternal deaths and complications from hospital infections, he became an advocate for cleaner maternity wards, which met significant resistance from his colleagues (although not as severe as what Ignaz Semmelweis faced almost a century in Austria for pointing out that doctors not disinfection their hands was routinely killing mothers).

From one perspective, I can greatly sympathize with where DeLee came from, as significant issues needed to be addressed (e.g., in 1913, the infant mortality rate was 13.2%). However, he failed to recognize many of them were due to the abhorrent living conditions of the time (which as I show here were also the primary driver behind the incredibly high mortality from infectious diseases).

At the same time however, some of his approaches (e.g., making women partially unconscious during labor and then pulling the babies out with forceps) were abhorrent (and explicitly detailed within his classic 1920 paper), and set the stage for a variety of other harmful and unnecessary interventions to hijack the childbirth process.

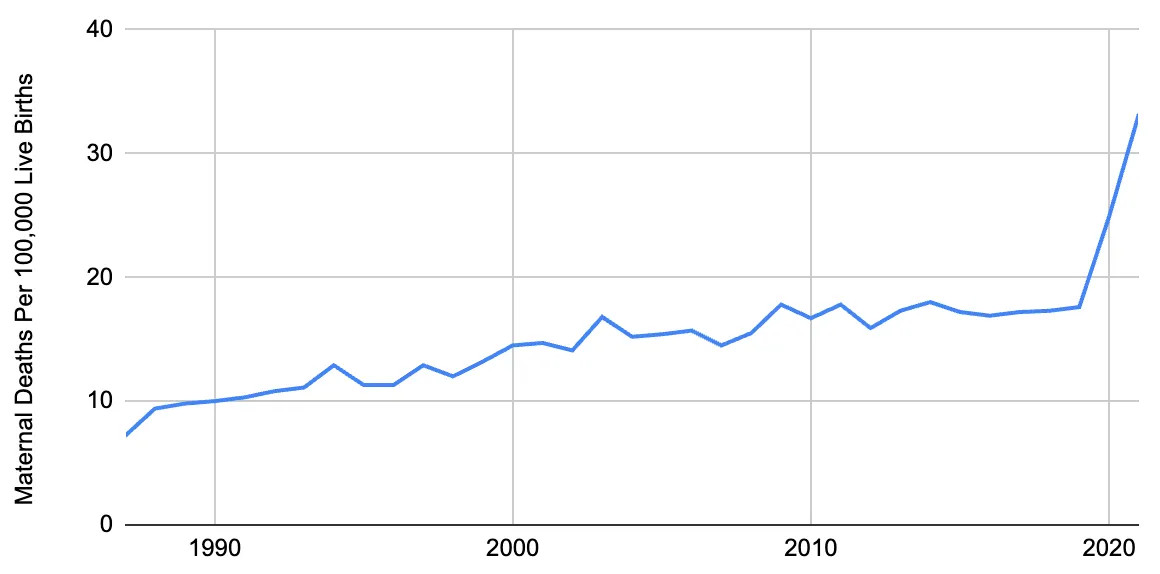

Worse still, he seeded the idea within the medical profession that childbirth was inherently pathologic and required a doctor to save the mother and child-despite the fact for most of human history, we had not needed them. Likewise, the maternal death rate was actually the highest between 1900-1930 (when DeLee's practices came into vogue), and it was only after years of deaths and mistakes that the standard of care began being improved and maternal deaths declined. Nonetheless, even now, over a century later, the United States still has a significant issue with these deaths (which is particularly noteworthy as during the period below, t hose deaths were declining in the other wealthy nations).

Note: another controversial doctor James Marion Sims, who in 1845 began experimental gynecological surgeries on African American slaves (without anesthesia-and operated some on individuals up to 30 times) and after roughly 4 years of work, perfected the surgeries enough to use them on white women (with anesthesia) after which, in the 1850s, he opened the first women's hospital (which was mired in controversy due to how barbaric some of his procedures were, their high fatality rate, and some of the unnecessary brain surgeries he did on black children). Nonetheless, he became one of the most famous doctors in the country (e.g., he was the 1876 president of the AMA) and is considered to be the father of gynecology.

At the exact same time DeLee's work occurred, a variety of federal and state initiatives recognized that the incredibly high infant and maternal mortality rates were connected, and that appropriate prenatal care could prevent them (e.g., Mother's Day was created at this time to provide maternal support to prevent those deaths).

Simultaneously, a debate known as the "Midwife Problem" unfolded, with some (e.g., doctors) advocating for the abolition of midwifery (largely to shield themselves from competition) and others supporting it with proper training and licensing (as they felt midwives could play a critical role in preventing deaths if utilized correctly). Laws were passed in some states (e.g., those that simply did not have enough doctors to attend childbirths) to regulate midwifery, and schools were created to improve midwifery standards. However, by the 1930s, the increased use of hospitals for deliveries made it possible to close many of these schools.

Fortunately, a 1921 Federal law provided for training nurse midwives, and in 1931 (owing to the increasing recognition of the failures of American obstetric care), a successful nurse midwifery school emerged (which amongst other things, had a maternal mortality rate of one-tenth that of the country). Their graduates then created numerous schools and created the modern discipline of nurse midwifery.

Note: in parallel, the Frontier Nursing Service (founded in 1925 by a British trained midwife) trained nurses and provided extensive midwifery (and medical care) to the woefully underserved inhabitants of the Appalachians, which ultimately resulted in a far lower maternal death rate ( roughly one third as much as the rest of the country). In turn, when many of its nurses returned to England at the start of World War 2, they also created a successful nurse midwifery program there as well.

Following this, in the 1940s and 1950s, due to limited existing opportunities to practice clinical midwifery, most of the graduates of these programs had to fill other obstetric related roles, and ultimately only a quarter served as midwives. In the 1960s, a variety of attempts were made to address this (e.g., having them work at hospitals where 70% of the births were taking place), and it was not until 1968 that more opportunities began to emerge (due to one school finding a way to integrate with New York's medical system).

Shortly after, a variety of rapid shifts occurred (e.g., key professional organizations endorsed nurse-midwifery, feminism came into vogue, the media promoting midwifery, federal funding for it, an explosion of childbirths from the baby boomers coming of age that the existing system could not accommodate) which propelled midwifery into the mainstream. In turn, many doctors began partnering with midwives, programs became officially recognized by the U.S. Department of Education, and public demand for midwife supervised home births exploded.

This increased demand quickly exceeded the available supply, after which there was a rapid proliferation of non-nurse midwives (lay midwives) with highly variable degrees of training (who had their first national meeting in 1977). By the 1980s, nurse-midwives were present throughout the healthcare system, and a split developed in the medical community between obstetricians who recognized their value and worked with them versus those who viewed them as economic competition that needed to be eliminated (particularly because there was now an overabundance of obstetricians).

Since then, midwifery has faced additional obstacles from the medical system but has continued to develop. Mixed opinions exist within the obstetrics field towards midwifery, and its accessibility varies. Since the 1990s, approximately 1% of births have been at home (although recently it suddenly increased to 1.5%).

Note: this abridged history necessarily omits the immense struggles countless incredibly dedicated midwives went through to make midwifery available to the public or just how much that work approved the abysmal obstetric care that existed throughout the country and the human cost that came with it.

A Standard Hospital Birth

When women go into labor, it is frequently viewed as a medical emergency that necessitates getting to the hospital as quickly as possible (e.g., this idea has been reinforced in television and movies for decades) and then struggling and having the doctor miraculously deliver the baby.

During this whole process, the following will happen.

• The mother will be placed in an uncomfortable and stressful environment (where many unfamiliar people enter and exit the room), be subject to repeated vaginal examinations, and typically placed on her back with the legs spread out.

• The mother will be placed on fetal heart rate monitoring (typically via the abdomen, but sometimes also through an electrode applied intravaginally to the baby's head).

• If the mother delivers too slowly, she will be given pitocin (oxytocin) to speed up the rate of contractions and may have her amniotic membrane prematurely ruptured.

• To mitigate her discomfort, she will often be given an epidural.

• Once the baby starts to come out, it may be pulled out with forceps or a vacuum extractor if the labor progresses "too slowly" or an issue arises.

• To prevent tearing and to make childbirth easier, mothers will often be given a prophylactic episiotomy, which preemptively cuts the vaginal opening to widen it.

• If any of the above goes awry, the mother will be converted to having a C-section.

• Once the baby is born, the cord will be immediately cut (and the placenta disposed of). The baby will typically be separated from the mother for a prolonged period (e.g., to go to a newborn nursery or the neonatal intensive care unit), and will receive a vitamin K shot and a hepatitis B vaccine and then have their blood drawn. Lastly, if the baby is a boy, circumcisions are often performed in the first days of life while they are still at the hospital.

• Finally, following this, if all goes well, the mother will go home with the baby in a few days, or a week if issues emerge.

However, while many of these steps can potentially save an infant's life, many of them create significant long-term complications, and many increase the likelihood more hospital interventions will be needed.

This in turn, touches upon a criticism of the medical industry-medical interventions often thrust you onto an assembly line that requires more and more of them (e.g., many psychiatric drugs are prescribed to treat the side effects of other psychiatric drugs). Typically, it takes time to see this process play out, but in the case of labor and delivery, the changes requiring additional interventions occur quite rapidly-whereas in contrast, almost none of this is seen outside of the hospital.

Note: I believe this bias towards excessive intervention in part occurs from obstetric units being understaffed (e.g., if a doctor is attending 6-10 mothers, the deliveries need to be artificially sequenced so that they don't occur simultaneously and accelerated so they aren't held up in one place) and due to OBYGN's having significant liability risk if anything goes awry with a pregnancy if the standard protocols had not been followed.

Any intervention that interferes with women's ability to cope in labor has enormous implications: it can destroy feelings of achievement and self-esteem. Women who feel they have coped have more confidence in their mothering abilities than women who feel traumatized by the birth process. Specifically disturbing to this aspect of common labor ward practice is the data of Robson and Kumar reporting an association between procedures in labor, such as artificial rupture of the membranes, and the delayed onset of maternal affection.

We'll now look at the issues with each of the previous approaches.

Note: as we go through these, consider that America currently spends at least 111 billion dollars on childbirth (which is twice that of most high income countries) yet ranks last amongst the high income nations in both infant and maternal mortality.

Birthing position

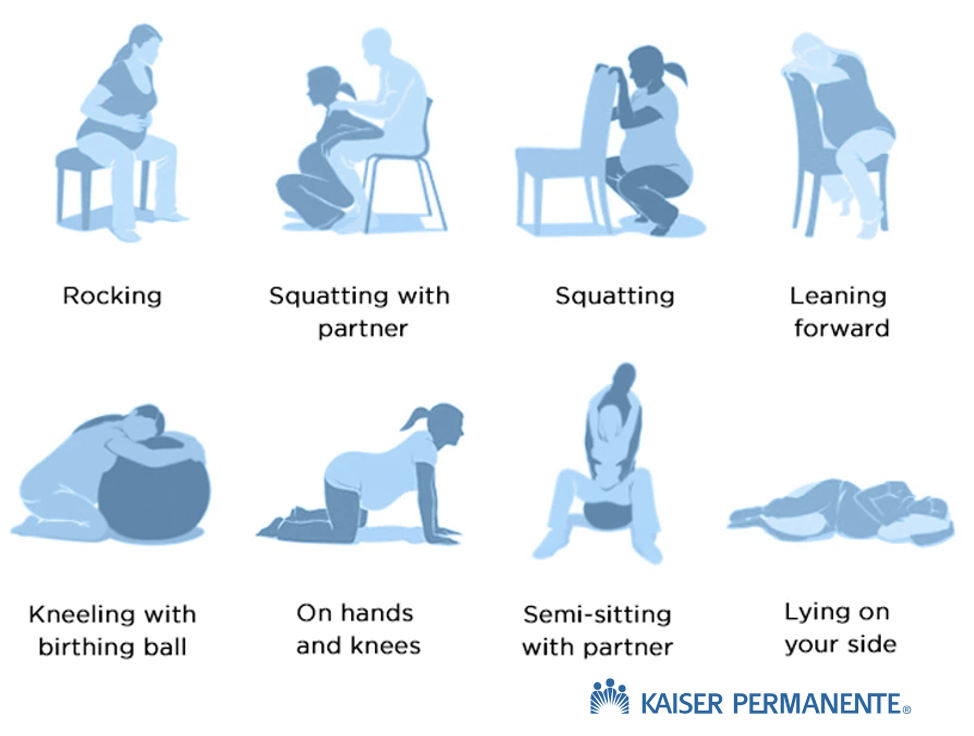

There are many different positions where a mother could give birth.

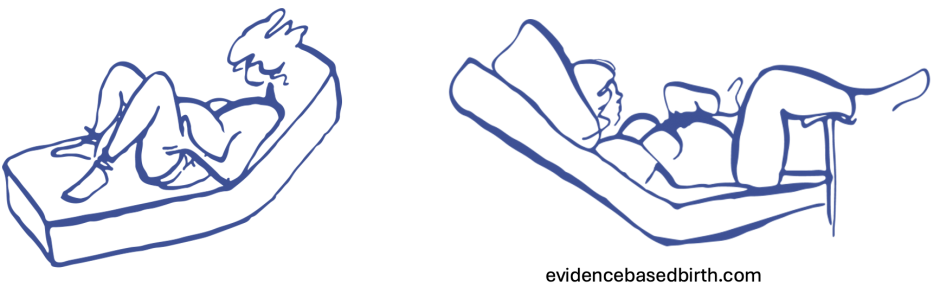

However, in most hospital births, mothers deliver on their backs with their knees up (e.g., a 2014 study of 2,400 hospital births found 68% gave birth lying on their backs, and 23% did so lying down while having their backs propped up).

These images are from a detailed article on birthing positions and the risks of lying down.

Note: The primary reason these positions are used at hospitals is that they make it much easier to manage hospital deliveries and train healthcare providers to conduct them (leading to them not being comfortable with any other position). Many also believe they serve to enforce a power dynamic where modern medicine is in control of the process, and by extension, its participants as well.

Despite this being the norm, and despite most healthcare workers knowing it is not the ideal position, it is quite controversial as:

•Lying down closes the pelvis making it harder to push the baby out. In contrast, squatting allows the force of gravity to help the baby come out and has repeatedly been shown via MRIs to increase the size of the pelvic outlet that the baby has to exit.

•Compressing the sacrum (by lying down or sitting) dramatically reduces the ability of the coccyx (or public symphysis) to move and accommodate the baby passing through.

•Different labor positions are often much more comfortable than lying on the back. For example, a study of 2992 home births (where mothers are allowed to choose their birthing position) found only 8% of mothers chose to deliver lying down (along with 23% who do so lying down with their backs propped up).

•Lying on the back can compress the mother's vena cava and thus the blood supply to the fetus.

In turn, a 2017 Cochrane review found that delivering while standing decreased abnormal fetal heart rates, accelerated labor, and reduced the need for assisted births (e.g., forceps deliveries) or episiotomies. A later 2020 review found those same benefits to a greater degree (e.g., there was a considerable reduction in perineal trauma).

Note: in many ways, this situation is analogous to the defecation (pooping) position we use, as when you sit in the normal position we use on the toilet, it partially closes down the rectum (hence making it much harder to poop), whereas if you squat, it's much easier for the process to occur naturally. However, despite this making a huge difference for bowel health, virtually no one knows about it, and our toilets are highly counterproductive to having healthy bowel movements (all of which are discussed further in this article about the forgotten natural ways to treat constipation).

Fetal Heart Rate Monitoring

An infant's heart rate can indicate if they are in danger (e.g., because their blood supply is being partially cut off), and can be assessed either with a specialized stethoscope or continuous ultrasound (which is what is typically done). Fetal heart rate monitoring forms a cornerstone of obstetric practices. It is almost always done in the hospital (which also incentivizes having the patient lie down as it's much harder to monitor in more natural birth positions).

However, while abnormal heart rates correlate to a variety of potential issues, extensive studies (e.g., consider this 2006 Cochrane review) have consistently found that when compared to periodic stethoscope examinations, fetal heart rate monitoring does not reduce death or disability but does increase the likelihood of a C-section by 66% and an instrumental birth by 16% (due to the abnormal heart rates making doctors want to save "at risk" babies).

Pitocin

Oxytocin is the hormone that stimulates uterine contractions. Because of this, synthetic oxytocin (pitocin) will often be given to induce labor or accelerate a delayed labor. Pitocin can be quite helpful, but unfortunately, it is frequently given at far too high of a dose (e.g., because a natural labor pace is deemed "too slow"). This leads to a few common issues:

•Pitocin can induce contractions before the cervix is ready to open (leading to the baby being pushed along but not able to get out), leading to prolonged labor that can require C-sections.

•Pitocin causes much stronger (and frequent) contractions, which are often quite painful (hence leading to increased pain for laboring mothers and a need for pain-relieving medications).

•Excessive uterine contractions can compress and interrupt the blood supply to the fetus, leading to abnormal heart rates and possibly C-sections.

•The perineum needs time to stretch during labor before the baby comes out, so pushing the baby out too quickly can cause it to tear (similarly, one study found pitocin makes anal sphincter tears during labor 80% more likely, while another found induced labors were twice as likely to have perineal lacerations).

Note: occasionally, the excessive contractions can also be too much for the uterus and rupture it.

•Excessive contractions increase the risk of maternal bleeding (e.g., one study found pitocin induced labors were 6% more likely to cause postpartum hemorrhages and increased total postpartum bleeding by 46%).

Because of the previous complications, excessive oxytocin can significantly increase the likelihood of C-sections (e.g., one study found that higher doses of oxytocin made women 60% more likely to need C-sections).

Note: common side effects of pitocin include nausea, stomach pain, vomiting, headache, and fever or flushing (while a more extensive list with the more severe reactions can be read on the FDA label).

Artificial Rupture of Membranes

Another procedure used to induce labor and accelerate prolonged labors is to rupture the amniotic sac (so the water breaks) despite the evidence showing amniotomies do not significantly accelerate labor. Conversely it:

•Increases the pain of labor (e.g., a 1989 study of 3000 women found two-thirds of them felt it increased in rate, strength, and pain of contractions and made them more challenging to deal with).

• Can cause the umbilical cord to drop before the baby (e.g., one study found it happened in 0.3% of amniotomies), which cuts off the fetal oxygen supply (e.).

• Increases the risk of infections (as the amniotic membranes protect the fetus from microorganisms).

•Increases the risk of C-sections.

Sadly, amniotomies are frequently done (e.g., in 40.6% of deliveries in Sweden), despite medical guidelines advising against them for routine deliveries.

Note: another long standing problem with amniotomies is that doctors in certain areas will not discuss the procedure with women before it is performed.

Epidurals

Roughly 70-75% of women who deliver in the hospital end up using epidurals, a procedure where a local anesthetic (e.g., bupivacaine or ropivacaine) and sometimes an opioid is injected into the spine in the space directly above the membrane that encircles the spinal cord so that everything below the injection site will become numb. While helpful for reducing pain (and often necessary, especially if hospital interventions have made the pregnancy more challenging), epidurals have a variety of complications such as:

• Increasing the risk of respiratory depression in the fetus by 75%.

•Reducing blood pressure (e.g., a study of 439 women, 41.9% experienced significant systemic reactions to an epidural including 36.2% having severe maternal hypotension). That loss of blood flow in turn, has been shown to cause 11.4% of fetuses to have a worsening heart rate and increased risk of C-sections.

Note: mixed opinions exist on the degree to which epidurals increase the risk of C-sections as some studies found it does not, while others did (e.g., this one found it doubled it, this one found it increased it 2.5X, and this one found an epidural plus pitocin increased it 6X).

•Causing long-term back pain or headaches (due to the membrane coating the spinal cord being punctured and leaking). While the headaches are thought to be rare ( around 1% of epidurals), I have seen so many women who developed this complication (until it was treated with a blood patch—which has its own set of issues). I think this risk needs to be seriously considered.

•Disconnecting the mother from birth (as she can't feel it) and negatively affecting her self-esteem (as she felt she could not cope with the labor herself).

Note: other side effects of epidurals include a few days of soreness at the injection site, nausea, vomiting, and a temporary inability to urinate.

Episiotomies

Episiotomies (surgically cutting the back of the vaginal opening and part of the perineum, then sewing it back together after delivery) used to be performed in the majority of deliveries under the erroneous belief it would help mothers by reducing tears, but now are less frequently done (e.g., in 1979, the episiotomy rate was 60.9%, while in 2004 it was 24.5% in 2004).

The major issue with this surgery is that the incision often will not heal well (whereas natural tears are more likely to), which can then lead to a variety of issues such as: perineal pain, infections, too much bleeding, scarring, urinary or fecal incontinence, pain during sex (which may require a prolonged period of abstinence), pelvic floor dysfunction, and emotional or psychological effects (e.g., some women have PTSD from the experience and wish they had not had the decision).

As such, it is essential to consider if you want to have an episiotomy before childbirth, and to be able to decide if you want to consent to it when it is potentially justified (which for context, the WHO has said applies to less than 10% of births).

Forceps and Vacuum Cups

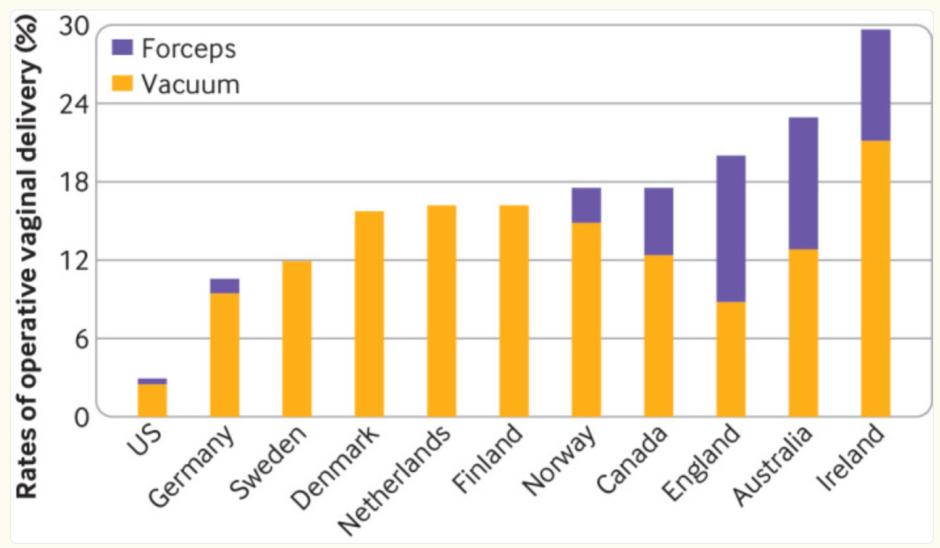

Frequently, if a delivery is progressing too slowly (or the fetus is deemed to be at risk) the infant will be pulled out by the head, either with clamps that grasp each side of the skull or a suction cup that attaches to the top of it. This practice has gradually become less frequent ( it's now only 5% of American births) due to increasing awareness about its harms and C-sections being done instead. Unfortunately, much of the world still has not recognized this.

When forceps are used, roughly a quarter of mothers experience injuries such as vaginal tears and sphincter injuries, while more severe complications (e.g., 3rd or 4th degree vaginal tears, are reported in about 8 to 12% of those undergoing forceps delivery). Likewise, when vacuum cups are used, 20.9% experience vaginal tears, and 2.4% experience postpartum hemorrhages.

Note: another study found 13.2% of mothers experience complications from vacuum cups.

When forceps or vacuum pumps are used for infants, a variety of injuries can occur, with severe traumas (e.g., injuries to the nerves for the arms, skull fractures, or brain injuries and bleeds) estimated to occur in 0.96% of births. A variety of other less severe injuries (detailed here) also occur such as bruises, lacerations, hematomas, and neonatal jaundice ( which occurs in 14.5% of assisted deliveries).

Note: the most severe complication I've come across from an assisted delivery was a baby with a challenging birth recently being decapitated due to too much force being used to pull the baby out.

Additionally, due to how malleable the skull is at birth (as the cranium has not yet fully formed), vacuum pumps and forceps can significantly distort the shape of the bones. While these changes are typically not considered concerning within the conventional medical field, many holistic schools of medicine place heavy emphasis on them, and we have met many adults who still had detectable dents from the forceps in their skull (along with many others who had decades of headaches).

Note: within these fields, vacuum pump deliveries are typically considered to be more problematic for the skull.

Skin to Skin Contact

At this point, I am relatively certain babies are supposed to go on their mother's skin after birth, as this is immensely healing for both of them, and in many cases can stabilize abnormal vital signs and sometimes save at risk babies (e.g., in less affluent countries, it's been shown to reduce mortality of low birth weight infants by 25% and I've seen quite a few miraculous instances of it stabilizing a baby).

Unfortunately, since everything in medicine is about streamlining the procedure and getting things done as quickly as possible, years of work went into pressuring hospitals to support this, and even now it's not universal. Because of this, it's important to verify you have this option and to push for it (including if your infant was delivered via a C-section) unless there is an urgent reason not to do so. Additionally, you should make a point to have skin-to-skin contact after childbirth.

Note: many of the benefits of skin-to-skin contact are ascribed to it releasing oxytocin, the bonding hormone that creates contentment, trust, empathy, calmness, and security (while reducing fear and anxiety) and also moving milk through the breast ducts. While this is true, I also believe there is a vital energetic exchange that occurs (which is arguably more important).

For context, benefits of immediate (and daily) skin-to-skin contact for the infant include:

• Shortening the time until a premature infant can be fed orally.

• Preventing low blood sugar in infants and NICU admissions for it (e.g., a 50% reduction).

• Improve the gut microbiome.

• Less crying and improved sleeping durations (which as any mother can attest is very important).

• Developing the emotional capacities of the brain (e.g., increasing empathy later in life).

• Improved behavior, social interactions, and cognitive function in early childhood.

• Reduced physiologic response to stressors in infants and improved maternal bonding.

• Enhanced cognitive development

While for the mother they include:

• Reduced maternal PTSD (and other negative emotions) following childbirth (e.g., feelings of fear and guilt in mothers who had C-sections).

• Decreasing maternal anxiety and fatigue.

• Reducing postpartum depression.

• Starting breastfeeding earlier, improving the likelihood, and duration of breastfeeding (e.g., by 24%), including after C-sections.

Note: many of these benefits have also been observed in fathers who have skin-to-skin contact with the infant (e.g., improved vital signs, crying, and feeding in infants, along with reduced anxiety and depression in the father).

Umbilical Cord Clamping

Typically, when a baby is born, the umbilical cord will be quickly clamped, and then (if around) the father will be given scissors to cut it so he can feel like he's part of the process, after which the placenta will be extracted and thrown away. The problem with doing this is that the blood inside the placenta (and the placenta tissue itself) is one of the most healing substances in nature, as it contains a large number of stem cells and vital growth factors.

This makes it vital for the baby to recover from the trauma of the birthing process; likewise, the placenta provides a critical source of nutrition for the mother.

Note: many hospitals will not allow you to preserve the placenta for encapsulation and consumption, while others may, provided you follow a set of procedures. As such, if you wish to do that (which I advise), it must be figured out before delivery.

Additionally, these materials provide the most ethical (and potent) source of regenerative medicine products available (e.g., cord blood stem cells, if used correctly, are often a miraculous therapy. A variety of very potent regenerative therapies can be made from the placenta, and the amniotic fluid provides an excellent source of exosomes).

Note: one of the many harmful things Biden did early in his presidency was having the FDA effectively outlaw umbilical cord blood stem cells (which largely killed the industry) and vaccinate mothers across America (as this has been shown to significantly impair the quality of their cord blood stem cells). Fortunately, shortly before the election, 𝕏 RFK announced he would end the FDA's prohibition on them.

In turn, various benefits have been identified from delayed cord clamping, particularly in premature babies (the most vulnerable to losing this essential blood). These include:

•Increasing the blood volume ( by up to a third) and the body's iron stores (which is critical for brain development in the first few months of life) along with decreasing the need for infants to receive transfusions (e.g., 55% less likely to in one study).

• Improving cardiovascular stability (e.g., blood pressure), and organ function (as more blood is available).

•Improved respiratory function (as the lungs depend upon blood coming in and out of them), which reduces respiratory distress (particularly since extended placenta blood flow aids the transition from umbilical to pulmonary circulation).

•Reduced intraventricular hemorrhages (brain bleeds) since the cord blood stem cells repair wounds (e.g., this study found a 60% reduction, while this study found a complete elimination of them [and seizures]).

•Reduced necrotizing enterocolitis (e.g., this study found a 41% reduction), a severe condition ( 25% mortality) that affects 3-9% of premature infants each year.

•Improved brain myelination, and neurological development.

Note: for most of history, cords were not clamped (it began in the 1600s), in the 1700s it was critiqued and by 1801, authors were warning that rapid clamping decreased an infant's health and vitality. Starting in the 1950s, research and practice opinions started emerging arguing against rapid clamping. Still, it was not until the 21st century that guidelines began advocating for slightly delaying when cords were clamped (e.g., in 2008 the WHO did, then in 2012 ACOG did for preterm infants, and in 2016 ACOG did for all infants). Despite this, only approximately 50% of US hospital births receive DCC (with the highest rates seen at hospitals that deliver fewer babies—presumably because they are not as rushed), and a 2009 global survey found most doctors either only occasionally practiced DCC or never did so.

In short, a good case can be made that many of the birthing complications we see arise from prematurely clamping the umbilical cord. As such, it's unconscionable that the medical field has been so resistant to delaying cord clamping. Over the years, a variety of rationalizations have been provided by the medical field for why this procedure should be done, but in my eyes, it's ultimately due to the fact there are too few healthcare workers in birthing units, so any step that can be rushed (e.g., saving a few minutes by clamping a cord) will be skipped—even when a small action can provide a profound benefit for the baby.

Note: ideally, you should not clamp the cord until it stops pulsating (arguably, you should wait even longer because some cord blood still transfers into the baby afterward). In many cases, this takes much longer than the minute hospitals allocate for delayed cord clamping.

Injections

After childbirth, infants are immediately given a vitamin K shot (within 6 hours) and a hepatitis B vaccine (within 24 hours), and the pressure to do these is so strong that if they are declined at a hospital, it can result in a child protective services referral.

In the case of the hepatitis B vaccine, there really isn't a reasonable justification for it as you can only get hepatitis B through sharing drug needles or sex, and the vaccine typically lasts for 6-7 years. In contrast, it exposes children to significant potential harm, particularly since its antigen mimics myelin and hence has the potential to create autoimmunity illness in developing brain tissue.

Note: the two answers I've heard over the years from insiders for why it's actually given then is either to habituate parents to bringing in their babies for pediatric vaccine appointments or so that the vaccine can be on the infant schedule and hence enjoy the liability protections afforded by the 1986 vaccine injury act.

In the case of vitamin K shots, the argument for them is that infants are often deficient in vitamin K (which is necessary for blood clotting) as it does not transfer through the placenta and instead must be obtained through breast milk. As such, without supplemental vitamin K, they are more likely to experience subsequent bleeding, which, without prevention, in the first 24 hours affects between 0.25%-1.7% of births and 0.004% of infants between 2-24 weeks of age (of whom, assuming the estimates are not biased, 20% die). Furthermore, while oral vitamin K can also prevent this, the effect is not as long lasting (it needs to be done multiple times), so a shot is considered a more effective way to ensure it does not happen (e.g., if the parent does not give subsequent oral doses).

In contrast, there is evidence suggesting that vitamin K injections create chronic health issues, so a subset of parents decline taking it (which in turn leads to a small number of infant bleeding events)—many of which could likely be prevented if safer shots were made (as the additives rather than vitamin K are the most likely issue). Furthermore, while I cannot prove this, I believe the actual issue is early cord clamping, and if proper delayed cord clamping were widely practiced, much of that bleeding would not occur.

Note: there is a surprising lack of data in this area, but from looking at all of it, my best is that the vitamin K shots prevent approximately 1 in 1000 children from dying. Conversely, 0.3 in 1000 children experience a severe reaction to the shot.

Lastly, there is quite a bit of evidence demonstrating that premature infants (gathered from NICU data) are more susceptible to sudden infant death syndrome following vaccination (particularly if multiple vaccines are given concurrently).

Note: there is also a bit of data that giving a mother antibiotics during can adversely affect the infant later in life (e.g., it has been linked to obesity, epilepsy, cerebral palsy, and asthma).

Cesarean Sections

C-sections bypass the birthing process by cutting open the abdomen and directly extracting the baby. While they are sometimes necessary (e.g., the WHO made a good case that in 10% of births, they prevent maternal and infant mortality), they are done far too frequently (e.g., in 2023, 32.3% of all births were C-sections).

Note: one of my least favorite statistics in medicine is that C-section rates dramatically rise at the times doctors typically want to go home. 1, 2, 3

Surgical Risks

Being a surgery, C-sections carry a variety of issues commonly seen with other surgeries like the mother needing a 4-6 week recovery period (which longer than that from a vaginal birth), a global 5.63% infection rate (which is a bit lower in the United States), and significant pain (at the most important bonding period of your life), potential reactions to general anesthesia and accidental organ injuries (particularly since some c-sections need to be done very quickly to save the baby's life).

Additionally, there are some surgical complications more unique to C-sections such as:

•Damage to the lining of the uterus creating adhesions and scars which cause the placenta to attach in the wrong place in future pregnancies (e.g. two C-sections make women 13.8 times more likely to have a placenta accreta).

•The weakened uterine scar can rupture during a subsequent delivery (especially if oxytocin is used), so one C-section can result in patients needing to have all subsequent births to be C-sections as well (particularly if the placental attachment becomes abnormal).

•The infant can accidentally get cut during the C-section (e.g., 1.5-1.9% get facial lacerations).

•The scars often cause significant issues for women for years if not decades (until they are correctly treated)—which in many cases they do not realize are the root cause of many of their issues until you point it out.

•The general anesthetics used for the C-section can increase an infant's risk of neonatal complications.

Note: C-sections also cause a variety of other issues, such as breastfeeding problems, worsened sleep, and emotional challenges (e.g., PTSD or anxiety).

However, beyond the surgery itself, simply bypassing the normal birthing process can also cause significant issues for infants.

Acute Risks

Hyaline membrane disease (respiratory distress syndrome—RDS) affects approximately 24,000 infants in the United States annually and is the leading cause of neonatal fatalities. The birthing process protects against this (e.g., studies have found premature C-section babies are 2.4-3.92 times more likely to have RDS 1, 2, 3), likely due to its mechanical pressure forcing excessive fluids out of the lungs.

Note: in 1979, Dr. Robert S. Mendelsohn (one of the trailblazing medical dissidents) discussed a recent study that concluded 6,000 of the 40,000 cases of RDS could be prevented by not bringing babies out of the womb before they were ready and then stated, "Yet the rates of induced deliveries and Caesarean sections are going up, not down. I can remember when a hospital's incidence of Caesarean deliveries went above four or five percent, there was a full scale investigation. The present level is around twenty-five percent. There are no investigations at all. And in some hospitals the rate is pushing fifty percent."

Chronic Risks

C-sections have also been linked to a variety of chronic issues, most of which are immunological in nature. For example:

• A Kaiser study of 8,953 children found C-sections increased allergic rhinoconjunctivitis (hay fever) by 37%, asthma by 24% (53% in girls and 8% in boys).

• Roughly 2000 studies have assessed the link between C-sections and asthma. From them, a 2020 meta-analysis found C-sections increase asthma by 41%, while a 2019 meta-analysis found a 20% increase.

• A Danish study of 750,000 children aged 0-14 assessed a few autoimmune diseases and found those born by C-sections were roughly 20% more likely to develop Laryngitis, Asthma, Gastroenteritis, Ulcerative colitis, Celiac disease, and Juvenile

Arthritis (along with Pneumonia and other lower respiratory tract infections).

• A later Danish Study of 2,699,479 births found that elective C-sections caused a 14% increase in diabetes, a 14% increase in rheumatoid arthritis, a 4% increase in Chron's disease, and a 15% increase in irritable bowel disease. Generally, the risk for these conditions was higher in women and for elective C-sections (with the exception of Chron's increasing by 15% after emergency C-sections). Another similar study also found C-sections significantly increased the risk of asthma, systemic connective tissue disorders, juvenile arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, immune deficiencies, and leukemia.

• A study of 7,174,787 births found C-sections made infants (in the first 5 years of life) 10% more likely to be hospitalized for infections (particularly respiratory, gastrointestinal, and viral ones).

• A study of 33,226 adult women found being born by C-section made them 11% more likely to be obese and 46% more likely to develop type 2 diabetes.

Much of this is likely due to C-sections disrupting the microbiome (which can persist into adulthood) as infants depend upon the vaginal flora (and external fecal flora) to initially colonize the gastrointestinal tract (as the microflora of the vagina are predominantly composed of the "good bacteria" our digestion needs and shortly after birth, the stomach starts producing stomach acid so other bacteria can't as easily colonize the GI tract). In turn, many studies have found C-sections significantly disrupt the microbiome, including a prospective trial that demonstrated that the degree of lasting microbiome disruption in an infant directly correlated to their likelihood of developing asthma and allergic sensitizations.

Note: one partial solution to this (which does not address harmful hospital microbes displacing the normal microbiome) is to inoculate the infant with the mother's vaginal secretions immediately after delivery. However, while compelling evidence has emerged for vaginal seeding in the last decade (e.g., this study and this study), it is not currently endorsed by the medical community, and most hospitals do not offer it.

Neurological Issues

Finally, C-sections have been linked to a variety of neurological issues:

• A mouse trial found C-sections led to behavioral changes and increased cell death in certain portions of the brain, while a retrospective MRI study of 306 children found that C-sections significantly reduced brain white matter and functional neural connectivity. A large 2017 study (published in nature) found that C-section children (ages 4-9) performed lower on standardized tests than vaginally born children and that this was not due to confounding variables, while a 2024 Nature study found C-sections caused lower motor and language development scores during specific age windows in the first three years of life.

A 2020 Czech study found 5 year old children born via C-section had poorer performance on cognitive tests than children born via vaginal delivery.

• C-sections have been found to increase the rate of ADHD by 15-16% and autism by 23-26%, while early onset schizophrenia has also been associated with C-sections (much of which may be due to C-sections changing the dopamine receptors in the brain).

Note: as this study shows, the increase in autism is strongly correlated to mothers receiving general anesthesia during the C-section.

• C-sections have been found to impair a newborn's ability to recognize familiar scents, make them more averse to being touched or hugged, and have poorer sensory integration, visual memory, and visuospatial perception. In parallel, mothers of C-section babies have been found to have less attachment to and more negative evaluations of their children.

Since neurological development is such a complicated process, it's difficult to say which factor (e.g., anesthesia, reduced maternal bonding, gut microbiome alternations) is ultimately responsible for these changes. However, many excellent healers I've talked to from a variety of traditions (e.g., the New Zealand Maoris) have shared that they noticed there is a loss of vibrancy and vitality in C-section babies which they attribute to them not "getting a spark" the vaginal birthing process facilitates (e.g., because the micro-motion within the skull is catalyzed by the compression experienced during the birthing process).

One of the most interesting conversations I had on this subject was with a doctor who shared that he was taught the vitality of infants directly correlated to how much they cried at birth (which is why, in the older days doctors would wack a baby soles to trigger a vigorous cry). In turn, when he and his colleagues attempted to help struggling infants with birth trauma by gently compressing the tops of their skulls to recreate part of the birthing process, they found that C-section infants would let out a brief but very vigorous cry, whereas children who had been born vaginally typically had a much softer cry—something they attributed to the initial birthing process not having catalyzed the cry they needed then (which is why it was so loud at the subsequent compression).

Note: this is somewhat similar to the observation in homeopathy that patients who can mount fevers tend to have stronger vitalities and better responses to homeopathic remedies, but as the decades have gone by, people have become less able to mount fevers and now have smaller responses to homeopathic remedies.

High Risk Births

One of the major factors in deciding what to do for a pregnancy is if you have a "high-risk" pregnancy. As I discussed in a previous article on prenatal-ultrasounds (which abundant data shows are not safe and hence must be used quite cautiously), determining what constitutes a "high-risk" pregnancy is quite subjective, and that designation being erroneously applied frequently results in a lot of stressful, unnecessary and potentially harmful interventions.

Note: we believe the most appropriate use of ultrasound is a very brief low-dose evaluation at 36-37 weeks (or when the mother goes into labor) to determine the position of the placenta and baby, whereas for most other routine uses (unless there are signs of an issue such as unexpected bleeding), the risk of ultrasound outweighs its benefits (and typically there is an alternative option that can safely get the needed information).

Typically, there are a few common situations that can require hospital births:

•The placenta is in the wrong place. This typically requires C-sections. However, in many cases, the placenta can move to the correct position, so if this is diagnosed early in pregnancy with ultrasound, it can lead to a lot of unnecessary stress.

•The baby faces the wrong direction with the pelvis instead of the head coming out first (a breech presentation). This is a fairly controversial area as many people I know will deliver breech babies (and it went well), but many others will not (as they have seen bad outcomes or infant deaths) following them (e.g., one large study found breech babies are 2.4 times as likely to die from vaginal deliveries). Because of this, I believe the best option is to fix the issue before delivery by moving the baby into the correct position (which frequently works—provided it is done correctly).

Note: if one of the infant's legs or shoulders is sticking forward, a vaginal birth should not be attempted.

•The baby is head down, but facing the wrong direction (not facing forward). In our experience, these often end up requiring C-sections as it's not possible to get the infant out.

•Twins are present. This does not necessarily require a C-section, but a variety of issues are more likely to come up, so it can be very helpful to have additional assistance nearby if needed.

•The mother already had a C-section.

•There are other characteristics of a high-risk pregnancy (e.g., the mother is older or obese, there is a concurrent maternal illness, the mother had preeclampsia during the pregnancy).

The Risks and Benefits of a Hospital Birth

Note: in America, a hospital vaginal birth is typically $10,000- $15,000 ($2,000-$5,000 with insurance), a C-Section is $15,000-$30,000 ($3,000-$7,500 with insurance)—although sometimes C-sections with complications can exceed $70,000 and a home birth (including the Midwife's care through the pregnancy) is typically $1,500 to $5,000 (which insurance sometimes covers part of). Many in turn, believe this pricing (and the fact the most cost-effective option, doulas, are never paid for) has created a business of being born that does not prioritize the mother and child.

Based on everything that's been presented thus far (along with the more subtle implications of these points), a strong case exists for eschewing a hospital birth entirely, as there are so many risks, particularly if you have a low-risk pregnancy. Conversely, our experience has been that a bit more than 5% of low-risk births ultimately end up needing a hospital birth (which can be quite stressful if you have to suddenly be transferred to the ER and be delivered by the obstetrician who is on-call).

Because of this, there is no correct way to approach this situation, and I feel a lot of that is ultimately due to how incredibly resistant the medical field has been to basic adopting approaches that take a little bit more time but greatly help the mother and child. For example, in 1991, the WHO created the "baby friendly hospital" concept (which incorporated a few of the basic things that should always be done), but three decades later, only 30% of American babies were born at hospitals with that designation.

As such, I believe the following are critical to do if you pursue a hospital birth:

•Be familiar ahead of time with what the entire birthing process entails and the choices you will have to make, as it is often incredibly difficult to figure all of that out in the middle of a delivery (which is essentially why I wrote this article).

•Strongly consider working with a doula (someone who helps with the childbirth process and afterward but does not have formal training), as the right doula can be immensely helpful. For instance, a Cochrane review showed doulas (or other sources of continual support) are associated with an 8% higher chance of spontaneous vaginal birth, a 25% lower chance of C-sections (also shown in this clinical trial), and a 10% lower chance of instrumental vaginal birth. Labors were also 41 minutes shorter, and women were 31% less likely to have negative childbirth experiences and 7% less likely to use epidurals. Additionally, there was less postpartum depression, and babies had a 38% lower chance of a low five-minute Apgar score. Likewise, this study found doulas decreased epidural use by 11.7%, and made women more likely to have a positive birth experience, feelings as a woman, and body perception.

Note: this study found training a woman's friend for two hours on being a doula provided many of the same benefits an actual doula did—illustrating both the vital need for support and how much room there is to improve this.

•It is extremely important to have advocates with you who do not stress you out, understand what you want during the delivery, and want to support you. This can include the father (ideal but sadly not always possible), a close friend you trust for the role (and are comfortable with having there), or an outside doula or midwife you brought into the facility with you (which can often be extremely helpful). Giving birth can be one of the most empowering and profound moments of your life, but it can also be incredibly painful and challenging, so whoever is with you needs to get that and be supportive rather than an added source of stress.

•Consider making many of the decisions outlined throughout this article (e.g., delayed cord clamping), and if possible, find the best hospital in the area, and identify an obstetrician who you feel comfortable with and who appears open to a more natural childbirth.

Conversely, if you choose to not give birth at a hospital, you need to:

•Make sure you are smart about it and do not endanger anyone.

•Find the right midwife (and doula) to work with. Midwife experience, skill, and how comfortable you will feel with each one varies greatly, so making a bit of effort upfront to find the right person can pay a lot of dividends (e.g., do multiple interviews or go to an event where you can meet multiple potential candidates to see who you have a resonance with). Larger areas will often have a midwifery community, so by connecting with them, you can get a lot of helpful guidance in this regard.

•Understand the difference between lay midwifery (less training) and a nurse midwife (more training). Generally speaking, nurses who are also trained to be midwives will provide better care and are much less likely to cause disasters, but at the same time, I have met excellent lay midwives.

•Make sure you have a good spot to give birth in (which a midwife can help you with).

•Have a plan in place in case you do need to go to a hospital.

•Finally, be sure you are already engaged in a robust pre-natal and pregnancy health plan (as this often dramatically improves labor and the longevity of the infant).

Note: from having reviewed the evidence, I can't say with certainty if hospital births have any mortality benefit for low-risk pregnancies. However, in high-risk pregnancies, they do reduce an infant's chance of dying.

The Forgotten Side of Medicine is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, please consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Optimizing Childbirth

As I've tried to show in this article, there are immense issues with how the medical system (still) handles childbirth. In turn, it is my hope a key component of Making America Healthy Again MAHA will be fixing them, as the unique moment we are in has the potential to change many long-standing issues in the medical system, such as those maternal activists have fought for decades to address (or finding ways to reduce the pressure on hospital staff so mothers can give birth in a more natural and relaxed manner).

Since this topic is incredibly important to me, I have spent years upon years searching for better ways to address many issues and dilemmas with childbirth. I have found some very helpful solutions that are still relatively unknown.

These will be reviewed in the final part of the article and include:

•What I now believe to be the best model for where to give birth

•How to mitigate many of the complications from C-sections and vaginal births (e.g., such as vaginal tears and hemorrhages, C-section scars, or an inability for the infant to breastfeed)

•Safe and effective anesthetic options for childbirth.

•The best options for cord blood banking vs. delayed cord clamping and placenta encapsulation.

•What you can do before and during pregnancy to ensure the optimal health of your child (e.g., how to prevent miscarriages and methods for correcting a breech baby) and counteract issues that come up during it (e.g., back pain, preeclampsia, and edema).

•A few other resources I've found to be very helpful for parents wanting to understand and navigate this challenging dynamic.