By Sven R. ARSON

As 2025 draws to a close, it is time to take inventory of the European economy. Unfortunately, it is not an uplifting experience.

To date, Eurostat has published numbers for gross domestic product and its components through the third quarter of 2025. If we calculate an average for those three quarters, the GDP of the EU itself has grown at 1.48% over the same three quarters in 2024. The euro zone is doing even worse: 1.35%.

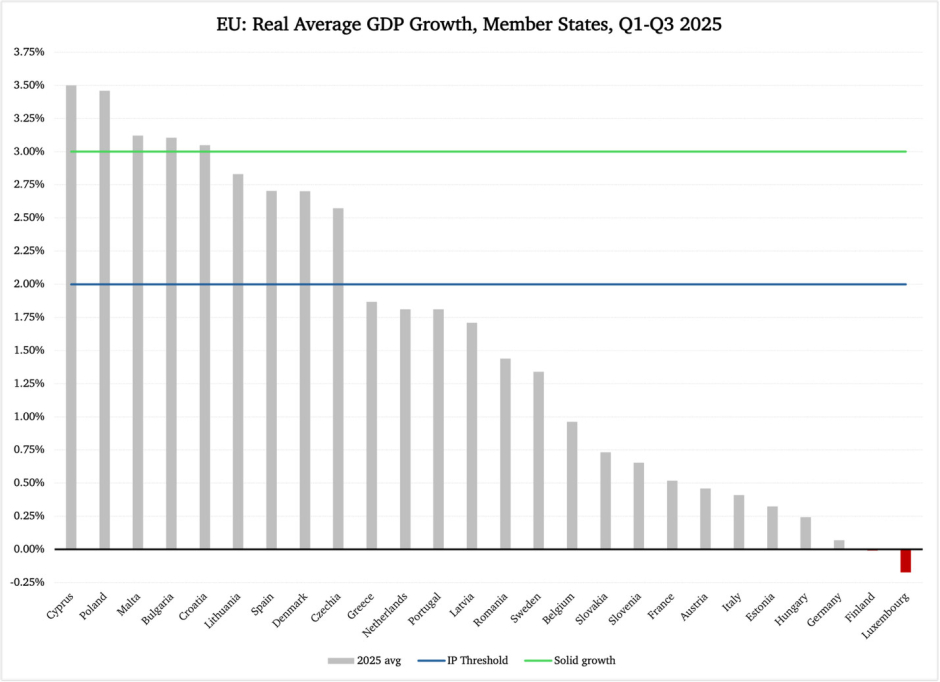

There is only one way to skin this cat: these are miserable numbers. A look at the EU member states tells an even more depressing story: of the 26 member states reported in Figure 1 (Irish GDP figures are so volatile due to foreign direct investment that they must be analyzed separately), only five reach the sound-growth threshold of 3%. A total of nine countries climb above the critical 2% level:

Figure 1

An economy that cannot sustain 2% real GDP growth over time will experience a slow, gradual decline in its standard of living. These economies typically also exhibit other signs of structural stagnation, a.k.a., industrial poverty: a youth unemployment rate above 20%, private consumption accounting for less than 50% of GDP, and government spending and taxes exceeding 40% of GDP.

This is not the time to examine the poor-performing economies in the EU from the full scale of the industrial poverty variables, but with GDP growth anywhere below 2%, the chances are good that these countries also meet the other criteria for perennial stagnation and a slow decline in standard of living.

Let us not forget that there are 11 countries in Figure 1 that fall below 1% real GDP growth. Among them are the two largest economies in Europe: France and Germany.

As an illustration of the dire state of the European economy, as I explained recently, the outlook on the immediate future is not at all better. The euro zone's combined GDP will barely grow by 1.4% through 2027. The EU as a whole can count on being very close to that figure.

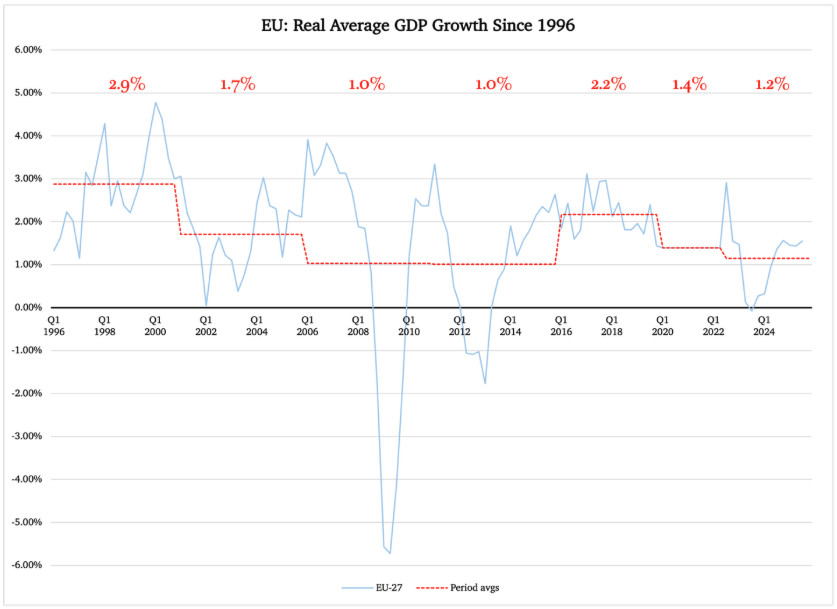

Figure 2 reports the real, average annual growth for the European Union as it is currently configured. (A long time-series analysis nullifies the violent swings in Irish GDP growth.) The light blue line marks the actual annual growth rates, reported quarterly; the dashed red line reports periodic averages, with the added numbers applying to each one of those periods:

Figure 2

The frightening message in Figure 2 is that these 27 countries have not been able to produce decent combined economic growth since the turn of the millennium. After the 2.9% average for the years 1996-2000, the rate fell to 1.7% through 2005. Then, due to the double-dip recession (that the American economy did not experience) with troughs in 2009 and 2013, the EU GDP grew by just a hair more than 1% for ten long years.

The period 2016-2019 saw a better average: the 2.2% more than doubled economic growth for a short period of time until the artificial economic shutdown in 2020. The pandemic-related economic regulations ebbed out in mid-2022; the average growth figure for the period from Q1 2020 until Q2 2022 was 1.4%.

Our post-pandemic economic period starts in Q3 2022 and ends with Q3 2025. Its 13 quarters averaging 1.15%-rounded up to 1.2%-in GDP growth.

Add to this the ECB forecast of 1.4% in 2025, 1.2% in 2026, and 1.4% in 2027, and it is downright scandalous that Europe's terrible economic performance is not top news all over the continent.

It would be simple to draw the conclusion from Figure 2 that the adoption of the euro has gradually thrown a wet blanket over the European economy. The fiscal rules that apply to all EU members are rigorously-or vigorously, depending on how one wants to see it-enforced within the euro zone. This gears fiscal policy toward budget balancing, not economic growth and generation of prosperity.

While the euro zone certainly has been a disappointment in terms of macroeconomic performance (something we critics pointed out already at the time of its introduction), it is certainly not the only explanation of Europe's crawling but seemingly unstoppable economic demise. Another factor has to do with the size of government spending, the burden of taxes, and the invasion of the regulatory state into the private sector. We need not look further than the detrimental effects of welfare state handouts on workforce participation and the depressing consequences of the 'green transition' on business investments.

On top of all these factors, Europe has made other short-term economic decisions with negative long-term ramifications. Foreign trade is one example: while the reconfiguration of U.S.-EU trade relations appears to have reached a productive point, Europe's initial reaction has no doubt taken its toll on the EU economy.

Furthermore, the sanctions on Russia have led to higher energy costs in Europe and lost economic benefits from trade. As a result of the trade sanctions, Russia continues to transition its economy off Western dependency. While its trade with the EU fell precipitously-again-in 2025, its trade with the so-called CIS countries continued to expand.

Although the CIS community is considerably smaller than the EU, consisting only of Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia, Tajikistan, and Moldova (with Turkmenistan having "participant status"), Russian trade with that community is now roughly three times bigger than its trade with the EU. The Russia-CIS trade is now worth $10bn per month; none of it is denominated in Western currencies.

The trade spans multiple industries- a few examples: raw materials like aluminum, copper, gold, iron, petroleum, and zinc; raw material-close products including aluminum wire, iron wire, and refined petroleum; manufacturing products from electronics to heavy machinery; chemicals; and food products.

There are moral arguments to be made for the sanctions, but those arguments must also be contrasted against their effectiveness-and their impact on the European economy. While the EU is in a state of long-term economic stagnation, as recently as this past summer, the Russian economy was still doing well, contrary to earlier Western predictions. As I explained in my analysis back in August, Russia appears to be reaching a point where its resiliency runs out; if it does, though, there will be little cause for celebration in a Europe that cannot even add 1.5% to its GDP every year.

Europe needs a crash commission on its economy. That commission cannot be led by politicians; it must be led by business leaders, independent economists, and other analysts who are not beholden to the current political structure in Brussels. It is clear beyond any doubt that Europe's political elite neither understands nor seriously cares about bringing growth and prosperity back to the continent.

Original article: europeanconservative.com