Joaquin Flores

The broader project to "Make America Great Again" cannot succeed if Americans don't have a chance to live long enough to see it realized.

The broader project to "Make America Great Again" cannot succeed if Americans remain sick, overburdened by healthcare costs, or worse, dead before they have a chance to live long enough to see it realized.

On the evening of November 9th, U.S. President Donald Trump announced that he believes the government shutdown may very soon be coming to end. Regardless of the final outcome of this little chapter of the ongoing partisan struggle, the entire fiasco points to a broader and endemic crisis affecting the country. The U.S. government shutdown may seem at first glance to outsiders as just another case of partisan posturing and grandstanding between 'tax and spend' liberals holding back 'small government' conservatives from hammering out an austerity budget. But this does not speak to scope of the crisis underway: federal workers are missing paychecks, SNAP benefits are delayed, flights are cancelled, and families are staring down skyrocketing health insurance premiums. The longest government closure in U.S. history has centered on one issue above all: healthcare. Expiring Affordable Care Act marketplace subsidies will be without funding, leaving millions without coverage until it is resolved, even if the ACA technically remains on the books as law. The standoff between Democrats insisting on subsidy extensions and Republicans refusing negotiation until the government reopens has made painfully visible a deeper truth: the American healthcare system is a machine built to extract wealth while rationing care.

At a time in history where the U.S. is trying to improve its image both at home and abroad, the healthcare crisis behind the government shutdown reveals fractured internal dynamics. Are these unfixable? The crisis is an international embarrassment: how can the U.S. frame establishing rules anywhere else when its own house is far from in order? The mantra has set in: America might be a nice place to visit, but don't get sick or injured there.

The ACA primarily serves people without access to affordable employer-sponsored insurance, including part-time workers, the self-employed, and those unemployed or in low- and moderate-income households. Its subsidies make coverage attainable for those who otherwise could not afford it. In plain terms, the structure of the ACA market, so-called 'Obama Care', is delivering a whopping 20% increase over last year to tax payers. This is quite a considerable pound of flesh being required by rapacious private insurance entities such as UnitedHealthcare, Anthem / Blue Cross Blue Shield affiliates, Cigna, Kaiser Permanente, Molina Healthcare, and Centene / Ambetter.

Of dollars and (political) sense

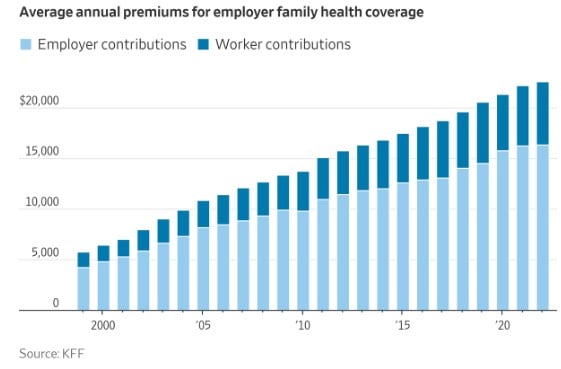

Since the launch of the ACA, average family premiums for a mid-tier Silver plan have climbed from about $900-$1,100 a month ($10,800-$13,200 per year) in 2010-2011 to roughly $2,200-$2,600 a month ($26,400-$31,200 per year) by 2022-2024-a 120-150% increase that far outpaced both wages and inflation.

Outside the ACA, talking private plans directly to customers or through employer co-paid plans, are still looking at a solid 9%-11% increase. So for a family plan currently costing $25,000 to $27,000, that increase would imply an increase of roughly $2,250-$2,970 annually in 2026. That's close to $30k annually. Shocking, but true. This is leaving many people to consider the value and cost really involved in the equation.

The ugly truth is this: ACA marketplace premiums are rising nearly twice as fast as comparable private plans more because insurance companies know the government will cover much of the cost, letting them push prices higher without immediate market pushback. That's what makes the present debate so frustrating. Employers either can't or won't cover many types of employees, and the ACA ensures greedy private insurance profit margins beyond even the semblance of a competitive structure. The bottom line is that America has a greed problem.

The debate goes beyond partisan lines, and points to an undercurrent developing for a few years in U.S. politics, where MAGA Republicans represent a working-class base, even if more rural than not, and are themselves often dependent on ACA marketplace subsidies. The Democrat Party's base, on the other hand, has developed further into those who can afford feel-good and symbolic politics: combined incomes over 300k-400k, with better jobs and their employers (or if bought individually by families) only looking at a roughly 10% increase. All this while Dems also hold onto legacy constituencies among retirees, lower-income urban dwellers, and public sector employees, who rely on a combination of ACA and non-subsidized private care models. As such, the old partisan matrix doesn't really hold as it did in past decades.

The shutdown also exposes the political dependency on the HIC. Private insurers donate significantly more to Democrats than Republicans, a change from decades past. This explains decades of incremental reform promises and why structural innovation has historically stalled. For the Democratic Party, rhetorical opposition to HMO power is constrained by the reality of donor dependence. For Republicans, rhetoric against the ACA competes with political realities: many conservatives now recognize that without subsidies, constituents would face prohibitive premiums.

This battle over healthcare reflects deeper disagreements about the kind of society Americans want to inhabit. Most Americans see health coverage as a basic right, a shared responsibility that should be guaranteed through collective structures. In fact, a 2020 Kaiser Family Foundation scientific poll, titled, "Democrats Like Both the Public Option and Medicare-for-all, But Overall More People Support the Public Option, Including a Significant Share of Republicans" found that 68% of all Americans want to have a public option. Fewer treat it as a commodity, something to be managed through markets, personal choice, and individual risk. But this latter opinion is what gets promoted across legacy media, regardless of whether it is considered 'liberal' or 'conservative'. This shows that the divide is largely a class one, and not a partisan one in the traditional sense. How much more than 68% of the public would support a public option if it was given equal treatment in corporate media? And with over 2/3rds supporting a public option already, why doesn't government move in that direction now? The filthy rich insurance industry has powerful lobbyists. What is considered bribery and corruption in other countries, is normal business in America.

The class struggle behind the debate

The 2025 federal government shutdown, now at around forty days, underscores how oddly interwoven government and healthcare have become, yet still in the interest of wealthy private individuals in America's owning class.

Healthcare in the United States operates like the military industrial complex, a 'Health Industrial Complex' if you will, where taxpayer dollars underwrite infrastructure, medical research, and pharmaceutical innovation, yet ordinary Americans pay premiums, deductibles, copays, and surprise bills. Losses are socialized, profits privatized, making it a dark corporatist system and the worst of both worlds. The federal scaffolding supports the HMO and insurance apparatus, and when that scaffolding falters, the human cost is immediate and visible.

At its core, the healthcare fight is also a struggle between socio-economic classes in the Weberian or Marxian sense; the 'have more and mores', vs. the 'have nots', though it never gets framed that way in mainstream coverage. Americans understand that the system is broken because super profitability in health insurance relies on denying legitimate claims. The system disproportionately benefits wealthy executives, shareholders, and large institutional insurers, while middle and working-class families shoulder the cost. This creates a dynamic where the very people funding the system have little control over it, while those profiting from it wield enormous political influence.

Luigi Mangione and the human face of frustration

In December 2024, the nation was shocked when Luigi Mangione, a private citizen frustrated by what he saw as a rigged healthcare system, murdered an insurance executive in Midtown Manhattan. Mangione's story resonated with many Americans because it highlighted a deep, simmering sense of helplessness. Here was a man confronting a system, in a regrettably vigilante fashion. Millions of families saw themselves in his frustration: workers trapped in jobs for the sake of benefits, self-employed families struggling to afford premiums, parents unable to ensure their children could get timely medical attention, and worse still: after paying all of this, claims are being denied.

Mangione became for many a symbol of the desperation born from decades of a system built to prioritize profit over health, even if his actions crossed a line into tragedy. A December 2024 poll taken almost immediately after Mangione's act, Most Americans say insurance profits and denials share blame in CEO's slaying, showed that 70% of Americans believe that insurance companies themselves bore some responsibility for the murder itself.

Luigi Mangione's actions, while condemned in the press, have illuminated a deep and widespread frustration with the U.S. health insurance system. Public opinion surveys consistently show that large segments of Americans view companies like UnitedHealth Group as extractive, opaque, and largely unaccountable. In this context, Mangione's murder of UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson has been interpreted by some not as an endorsement of violence but as a symbolic outburst against a system that leaves families burdened and often 'sentenced to death'. For international observers, the episode reveals more about the structural pressures on ordinary Americans than about the individual who committed the act.

America's health industrial complex

The Health Industrial Complex, or HIC, is built to scale. Insurance companies operate quasi-monopolies, using algorithmic pricing and opaque networks to maximize revenue. Patients are taxed twice: first through government support that underwrites the system, and second through out-of-pocket costs for services they nominally 'own' through coverage. Copays, deductibles, and high premiums ensure that even minor health events like an ER visit for a cold, lab work for routine blood tests, become expensive even with insurance.

The parallels to the military industrial complex are uncanny. Both systems consolidate power and profit through scale, with government underwriting capital expenditure while leaving the public to fund consumption. In healthcare, however, the cost is personal: families' financial security, wellness, and longevity are at stake.

What if families just pulled out? Over ten years, they could save or invest nearly $280,000, enough for a new home, business expansion, or major lifestyle improvements. Putting aside just 10% of that for healthcare needs, and willing to travel abroad to have a catastrophic health crisis addressed, would be an immediate and realistic solution. Instead, the American system funnels those same dollars into insurance overhead, administrative bureaucracy, and shareholder profit. But where would they be if they needed a simple doctor's visit, or prescription drugs? Setting aside catastrophic events, this is all that most people really need.

The Trump-Kennedy MAHA approach

Trump's prescription drug website, TrumpRx.gov, coming in January 2026 aims to give Americans direct access to lower-cost medications by bypassing traditional pharmacy middlemen, effectively reducing out-of-pocket spending. His 2020 executive order sought to implement a broader plan for price transparency and international reference pricing, which the Biden administration subsequently reversed, leaving patients to navigate higher costs through conventional insurance channels. Robert F. Kennedy Jr.'s concierge plan, announced in June 2025 and a concrete part of his MAHA agenda (Make America Healthy Again), bypasses the HMO apparatus entirely. The program is structured around direct primary care, telemedicine, and preventive medicine. For $75 a month, patients would be able to access a physician 24/7. Health savings accounts would cover gym memberships and wellness programs. Workplace clinics would offer basic diagnostic services and preventive care on-site. Teleconsultations allow for early diagnosis of common conditions, from seasonal allergies to chronic disease management.

The concierge plan remains more aspirational than implemented, and it has not been fully funded in the recent federal legislation. According to a detailed analysis by KFF Health News, while the OBBB (One Big Beautiful Bill) passed on July 4th of this year, included a much needed $50 billion "Rural Health Transformation Program" aimed at increasing access to care in underserved areas, though it does not allocate specific funding to the nationwide concierge or direct‑primary‑care model Kennedy promotes. Private insurers are a powerful lobby, and it was frustrated there.

Rather than legislating universal access through Congress, the concierge (etc.) plan offers Americans an alternative so practical, accessible, and cost-effective that the existing HMO structure becomes almost obsolete. The plan restores the doctor-patient relationship, eliminates prior authorizations, and removes network restrictions. Insurance, in this framework, is optional rather than compulsory.

Kennedy and China: Preventive care and telemedicine

Kennedy's plan apparently borrows from China's integration of preventative focus, modern communications technologies and AI, tools that remain underused in the United States, to deliver care more efficiently while lowering costs; an approach the old private versus public option debates never managed to address.

Early diagnosis reduces the cost and complexity of care while improving outcomes. Telemedicine allows patients to consult a physician without leaving home, cutting unnecessary ER visits and hospitalizations, and infrastructure space and overcrowded waiting rooms, where contagious disease also infamously spreads. Workplace clinics and health savings accounts incentivize wellness. In essence, the RKK Jr. plan operationalizes the idea that healthcare should prevent sickness rather than merely pay for treatment.

Three generations of Americans have been conditioned to accept high cost, complexity, and intermediary-based care as inevitable. The concierge idea demonstrates the opposite: simple, direct, affordable, and preventive. If widely adopted, it could eliminate the middle layer of insurers and administrators whose fees inflate costs without improving health.

Concluding with lessons from history - Bismarck (Not Kaiser!) and pragmatic conservatism

Otto von Bismarck, Germany's Iron Chancellor, implemented a multi-payer universal healthcare in 1883 not from ideological zeal but from conservative pragmatism. He understood that healthy workers were productive and happy workers and that a social fund could neutralize socialist agitation. Similarly, the concierge plan could deliver what progressive activists have long demanded: universal access, preventive care, and cost control but through conservative, market-based mechanisms.

And here we have Bismarck vs. Kaiser (Permanente). These proposals demonstrate that social benefit and conservative governance are not mutually exclusive. The Kennedy plan mirrors this philosophy placing pragmatism first, ideology second. It bypasses political gridlock, sidesteps partisan antibodies, and provides a functional alternative to entrenched monopolies.

Kennedy's concierge model builds on this by using telemedicine, AI diagnostics, and preventive strategies to streamline care and reduce unnecessary spending. Together, they suggest a modern public option that maintains quality and accessibility while harnessing technology to lower costs and expand coverage without relying on the traditional Health Industrial Complex. Ultimately, these innovations, a Bismarck-inspired public-private coverage and Kennedy's concierge approach using telemedicine and AI diagnostics, go beyond the immediate struggle over funding the ACA.

Yet the record-long government shutdown, combined with extreme expressions of anger like Luigi Mangione's murder of UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson, are symptomatic of deeper systemic failure. As long as Americans face a broken system and a sense that the institutions meant to protect them are captured by corporate interests, these crises will recur, eroding trust in U.S. institutions both at home and abroad until a comprehensive fix is implemented. The broader project to "Make America Great Again" cannot succeed if Americans remain sick, overburdened by healthcare costs, or worse, dead before they have a chance to live long enough to see it realized.