By A Midwestern Doctor

The Forgotten Side of Medicine

July 12, 2025

One of my longstanding curiosities has been what universal laws govern the reality we inhabit, and I have gradually concluded one is "the law of equilibrium," which states:

•Any process we observe is the product of competing forces balancing each other out to an equilibrium point.

•While it is sometimes possible to shift the equilibrium point (e.g., by mass poisoning the world with COVID vaccines), in most cases, systems will typically return to their equilibrium point.

•While the equilibrium sometimes rapidly re-establishes itself, it can often take decades, if not centuries, to do so. When viewed over time, these forces propagate across generations and eventually return to their equilibrium.

Furthermore:

•Humans throughout history continually overestimate their ability to suppress the equilibrium's restoration and engage in a variety of extreme but ultimately futile tactics to prevent it.

•The internet has rapidly accelerated the speed at which at which societal equilibria reassert themselves, and as the speed of the internet increases, so does the speed of the "reequilibration."

COVID Distorts The Equilibrium

Throughout my life, I have watched a gradually increasing encroachment on our health by predatory entities that prioritize profits over people (e.g., synthetic agriculture, processed foods, chemical manufacturing, and the pharmaceutical industry). Each of these follows the same pattern-something new gets introduced as "safe and effective," people notice the issues and object to it, science, media and the government conspire to suppress those objections, and then once it's normalized, something even more egregious is done the next time.

In turn, I've tried to show here that the unbelievable things we saw with the COVID vaccines were, in truth, simple repetitions of an existing pattern, that began over a century ago with the smallpox vaccine (which arguably were worse and whose mandates more widely protested than the COVID vaccines). Sadly, while healthy skepticism existed towards vaccines and the media to varying degrees called out the government's disastrous vaccines programs (e.g., the hot polio lots they released or the rushed and unnecessary swine flu vaccines), in 1997, the FDA legalized direct to consumer drug advertising, allowing the pharmaceutical industry through the mass media to dominate the narrative, at which point the only places these objections could be aired were the alternative media, where they in turn were dismissed as "fringe conspiracy theories that no credible outlet would touch."

Note: the HPV vaccine (approved in 2006) had many of the same issues the COVID vaccine had and when the injuries piled up, the FDA and the CDC simply did everything they could to sweep them under the rug just like COVID. Likewise, this issue is not unique to vaccines. For example, the SSRIs had serious issues with mind-altering suicidal and homicidal behaviors and rapidly became the most complained about drugs in America, but the FDA instead fought all efforts to give a basic safety warning on them and gagged their scientist who confirmed they caused children to kill themselves.

Depending on how you look at it, the good or bad thing about COVID was that it was the most extreme version we've seen of the previous pattern (e.g., ridiculous, over-the-top, and hateful vaccine marketing coupled with the first adult vaccine mandates our generation had experienced), and it happened to be both an incredibly dangerous, unneeded and ineffective vaccine.

Because of this, it was a shock that woke a lot of people up to something being seriously wrong with our medical system, and created a loss of trust in our institutions and medicine which has never been seen before in my lifetime-best demonstrated by a recent large JAMA study of 443,445 Americans, which found that in April 2020, 71.5% of them trusted doctors and hospitals, while in January 2024, only 40.1% did.

In short, I would argue, the medical industry got "too greedy" and effectively killed their "goose that laid the golden eggs" through their conduct during COVID, which was further worsened by leading Trump to go all-in on a vaccine before the election and then delaying it at the last moment, as Biden was presumably a more profitable president for the industry-an approach that worked until Trump was re-elected.

As such, I would argue the above illustrates how a distorted equilibrium will reassert itself, and the major mistake the COVID cartel made, like many before them, was thinking that with enough force, intimidation, and suppression, that they could stop it from happening, particularly since they had already planted so many seeds from earlier campaigns that they were able to sprout into a full-fledged resistance against them once the soil was right.

Questioning Doctors

Calley Means recently shared something quite noteworthy about the loss of trust in medicine that I felt merited further discussion.

I recently had a conversation with a friend who runs a clinic network of 1,000+ MDs.

She said the main conversation among doctors is frustration that patients are asking about the "root cause" and "more natural cures" for their conditions.

She said 0% of patients asked these questions five years ago, and now 80% of patients do.

Her doctors see this trend as a negative thing, and spend their time deriding the MAHA movement and social media personalities in the break room.

These clinics focus on dermatology and make money selling drugs and procedures. Many dermatological issues are tied to root cause issues (diet/lifestyle) and not a lack of cream or injection.

On Reddit boards, countless medical professionals are decrying these "root cause" questions.

I think this represents a major shift/dynamic happening in medicine that should be openly discussed. Are patients right to be asking more questions about the root cause, or are the doctors right to be deriding Americans for taking health into their own hands? To be asking about food, exercise, over-medicalization, and lifestyle habits...

Should patients trust their doctors on chronic disease management? Can patients actually reverse their conditions and thrive if they explore the root cause? Are the answers simpler and more under our control than we believe?

I think the answer is clearly yes. I hope the trend of patients asking doctors for the root cause doesn't slow down, and it not only changes how we practice medicine, but also changes our culture to be more empowered.

If you have an acute condition that will kill you right away, see your doctor and listen to them. Our system is a miracle at addressing these acute issues. But that's less than 10% of our spending.

Our system's failure at chronic disease management has economic, national defense, and spiritual effects that are existential.

We need to have respect for our food and our soil. We need to cherish breastfeeding and natural food... We need to ensure kids are away from their phones and outside running around... We need to rejuvenate a grounding in the spiritual...

These are the messages our healthcare leaders should be repeating again and again - and that light is starting to shine through, despite aggressive resistance from hard-working doctors whose income and identity are undeniably tied to the broken status quo.

Beyond the fact this again represents the equilibrium reestablishing itself, it also raises many important points I felt merit discussion.

Physician Reimbursement

One of the major dilemmas in healthcare has been how to appropriately reimburse for it, as:

• If it pays too little, healthcare workers will not be willing to do it, particularly society's "cream of the crop" who, based on academic merit, are selected to enter our medical schools, and in turn, they help establish medicine's credibility by having the most (academically) talented members of society lead the profession.

Note: since most of the "humanistic" aspects of a medical application are very easy to fake by saying all the standard buzzwords, the medical school process tends to select for high performers who are too "in their heads" (rather than their hearts), some of whom are only going into medicine for the money.

• If it costs too much, many people (or eventually the government) will not be able to pay for it.

• If specific services are reimbursed for at a high rate, physicians will inevitably gravitate their practices towards doing as much of them as possible to increase their incomes (e.g., here I showed how numerous neurosurgeons at one hospital each billed over 50 million dollars in 2015-something which can only be done by rushing and majorly cutting corners on surgeries which often were not needed in the first place).

Note: another field this is a huge problem is in orthopedics, as orthopedic surgeons make their money off their surgeries, and in many cases will operate when the surgery is not appropriate. In contrast, the most ethical ones I know tend to work for HMOs like Kaiser where their salary is set rather than being dependent on how many surgeries they perform.

• Likewise, many medical specialties have bread and butter procedures (e.g., pelvic exams in gynecology or vaccinations in pediatrics) which are routinely done at visits to support the practice's income. While some of these are relatively benign and have some value (e.g., ENTs cleaning a patient's ears) others often cause more harm than the benefit they provide. In the case of

Note: In many studies I've reviewed, the benefit of these routine screening exams or treatments is far less than portrayed (to the point the justification of paying for them is highly suspect), but at the same time, they are arguably justified as they subsidize the doctor staying in practice (and providing care to the area) and more importantly, noticing if something else is significantly wrong with the patient which would not have been recognized had they not seen the doctor.

Over the decades, I've seen various attempts and debates to address this conundrum, but in my eyes, they've essentially made things worse. For example:

• They've let the American Medical Association have a committee that effectively sets the government reimbursement rates for specialities. To some extent, this is a valid approach, since every speciality needs adequate reimbursement to be sustained, and specialities which require more training (e.g., becoming a neurosurgeon requires 11 or more years of medical training)-all of which the government would be unlikely to do correctly. Unfortunately, this process is also ripe for exploitation and conflicts of interest, so not surprisingly it has led to massive increases in speciality reimbursements.

Note: one of the many important policies RFK has advocated for is reforming this process so the medical profession cannot set their reimbursement rates.

• Switching from paper charts to electronic medical records (EMRs) was touted as the solution which would address all the problems in healthcare, but in reality, it just made doctors take way longer to write their notes rather than spending it on care (hence why doctors spend so much of their visits with you in front of the computer), and often they would copy paste the same thing into each one.

Note: per my understanding, the government push for EMRs (despite them harming patient care) came from them taking longer for doctors to fill out, and hence reduced their ability to submit insurance charges (saving the government money), a trend that may change as AI makes it possible to rapidly generate generic medical notes.

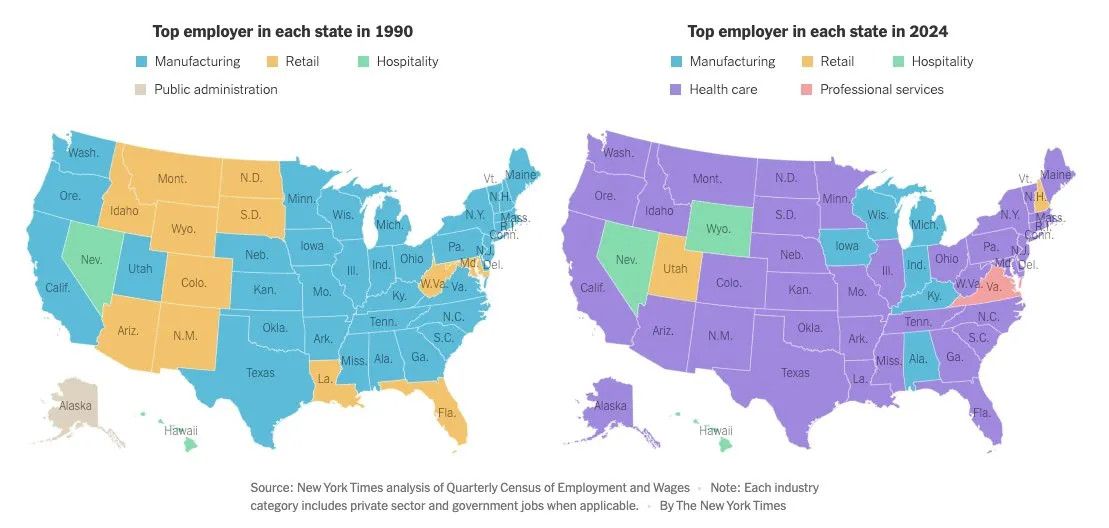

• Numerous regulations and requirements designed to make medical care 'better' have led to increasingly onerous practice requirements for doctors to comply with, making more and more medical spending to go to things besides healthcare (e.g., administrative compliance) and it has become nearly impossible for many doctors to maintain their own private practices. Because of this, more and more of them have been shifted to corporate employment where they have far less autonomy in what they can do (e.g., most knew they could not object to the COVID vaccines as they risked termination or being reported to the medical boards) and those employed are constantly under pressure to see more and more patients in shorter times-making patients "who want the root causes" non-functional for their practices as it takes up too much time.

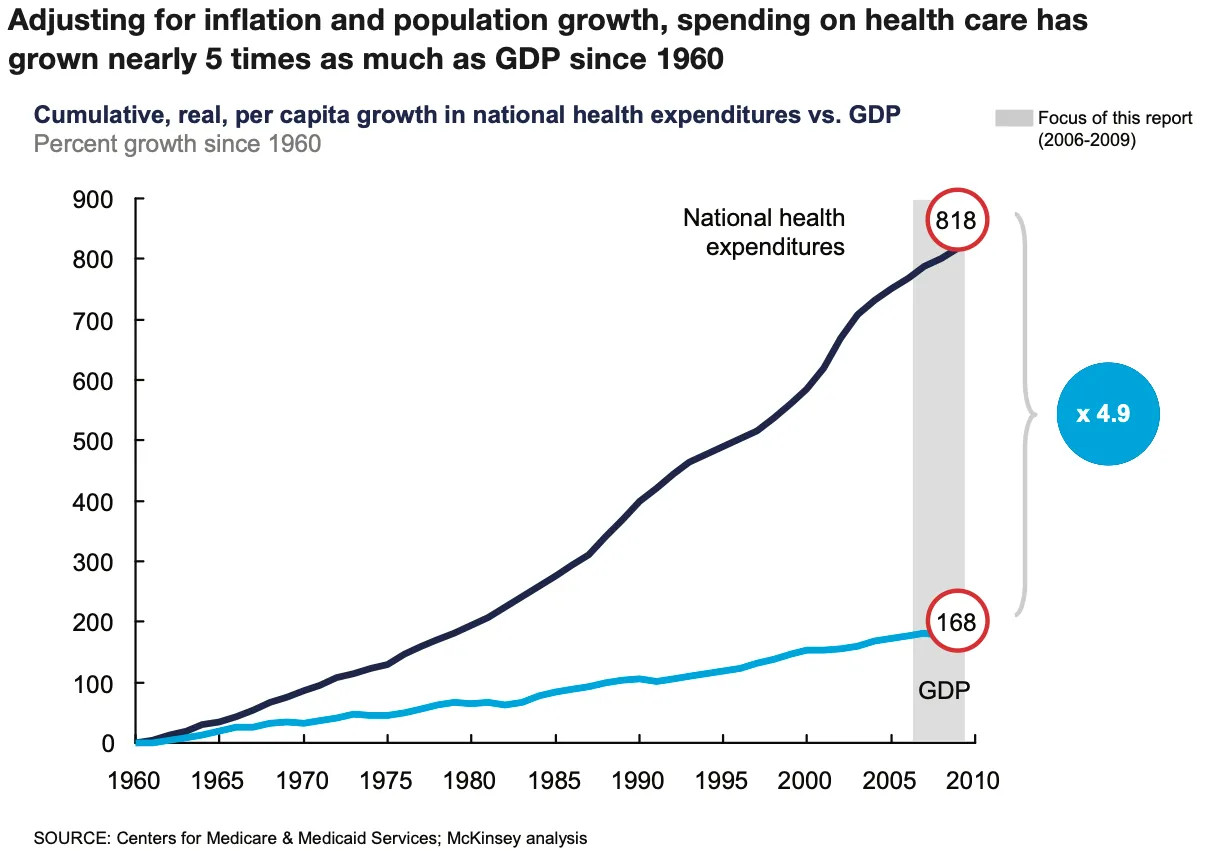

Unfortunately, as we all know, these attempts have not been successful, and as time goes on, healthcare consumes an increasing share of the economy (currently 17.6% of GDP) as our population becomes sicker.

Standard Medicine

No matter how you dice it, medical education is quite challenging as there is simply too much to learn, and even the "brightest" students adopt a triage mentality where they cut out things that aren't necessary (or low-yield) for exams so they can pass and get a degree. Because of this medical education typically:

• Covers many aspects in a superficial manner (e.g., just learn the classic indications, simple mechanisms of action and commonly recognized side effects of drugs).

Note: this is quite problematic as many of those simplistic facts students memorize aren't always entirely correct (or become evidently contradictory once you take the time to understand them). However, since students are under such pressure to memorize them, they take the facts as verbatim facts they don't question and become quite haughty towards those who do.

• Focuses on the key medical products (e.g., how to use pharmaceutical drugs along with the key microbes and their pharmaceutical treatments, understanding what aspects of the body each speciality is responsible for, how to interpret imaging studies, and how to understand surgery well enough to want to go into it or refer patients to it) along with basic skills necessary for being a doctor (e.g., being able to recognize potentially life-threatening conditions, conducting a physical exam with enough details to complete a medical note and writing billable medical notes).

Note: there is also a strong focus on anatomy and physiology, which along with recognizing key diseases and medical emergencies, in my eyes represent some of the most valuable aspects of conventional medical training.

• Cuts out a lot of the subtle aspects of medical science and doctoring that make you an effective clinician (e.g., medical ethics). Because of this, there is always a subset of medical students who have that inherent capacity and excel at being clinicians but very few learn it through their training. Put differently, standard medical training doesn't really cover what is needed to make people healthy as there is never enough time for that and again and again, I hear stories of medical educators who try to incorporate it but get pushed to the side due to limited curriculum time.

Additionally, while I can't prove this, I also strongly suspect a key reason why they aren't lifestyle treatments and natural therapies aren't focused on is because they aren't possible to monetize, whereas endless prescriptions and referrals for medical services feed the industry. This point is commonly referenced in regards to most medical schools for having minimal training in nutrition (which is actually arguably a good thing since what's done tends to focus on processed food dogmas, such as cholesterol being bad for you). However, it extends to far more, and is often encapsulated by the concept "Western Medicine is the only medical system in human history that does not recognize an innate health within the body that facilitates healing.

Note: I believe one of the major reasons the medical community has had such a great focus on DEI is because it gives them an easy scapegoat (the reason our medical system is abjectly failing America, particularly the poor, is because we don't have enough diversity in our doctors, rather than any of the actual issues the system does not want to discuss).

In contrast, many natural schools of medicine put a much greater focus on training doctors to facilitate actual healing in their patients. Unfortunately, I find graduates from these programs often can't recognize critical medical conditions (as their training doesn't focus on it) and in many cases, their training tends to be fairly linear and reductionistic (much like conventional medicine) so, while they are more equipped to heal, the same problem tends to emerge where the practitioners have the same things they do over and over and won't go outside their box to try and have a broader understanding as to how heal the patient.

Additionally, in many cases, to earn acceptance from mainstream medicine (and access to reimbursements) these professions sometimes shift to a much more conventional model (e.g., many of the leading naturopathic medical schools were not willing to criticize the vaccines and even mandated them despite the founders of naturopathy being vehemently against vaccination).

Trusting Experts

One of the things I find so fascinating about medical history is how often an event in the far distant past continues to ripple out into the present. One of my favorite articles," The End of Propaganda,"gives an excellent illustration of this. To summarize (with a few additional thoughts of my own):

•Modern technology and the emerging science of psychology enabled the creation of propaganda apparatuses which greatly exceeded anything that had been created in history (e.g., it birthed public relations, a fusion of marketing and propaganda which has been remarkably effective at controlling the American public for a century).

•At this time, there was a major debate on if it was appropriate to use propaganda to control the public. One side argued that society had become too complex for the public at their level of education to understand the issue well enough to make the correct decisions for society, so properly qualified experts needed to make them and mass propaganda was necessary to prevent the ignorant masses from derailing an advancing society. The other argued propaganda's removal of people's free will was antithetical to the idea of democracy, and that the public could be educated to meet the demands of our new world.

•Eventually, the propagandists won, in large part because Hitler was so successful with propaganda in Nazi Germany that the Allies feared the war would be lost if they did not use propaganda. As such, since that time, propaganda (and public relations) has more and more become integral to our society and public policy making has transformed from"what is agreeable enough for the public to support it"to"is there a viable propaganda campaign that can enact this policy."

•A cornerstone of this new system of government was enshrining experts and then paying them off to spout whatever the current orthodoxy is. In parallel, the media and society began placing immense weight on credentials (e.g., college was portrayed to the public as salvation and doctors), with doctors, in their white robes, seen as the new priests holding up the system we all trusted—while in parallel any dissident credentialed experts were heavily marginalized by the media and scientific orthodoxy.

Note: in many ways, this corruption of experts is a shame, because many have pivotally important ideas, but due to the public waking up to how often the scientific community lied to the public to advance political agendas, our trust in experts, which is sometimes quite valuable, has waned. In turn, I have seen more and more posts from scientists lamenting how hard it is to be a scientist now because"science is under attack"without realizing either what they did to cause this, or that rather than"being under attack"they simply no longer have the blind trust they previously received when asserting questionable"facts"to the public.

Medical Arrogance

Over the years, I have heard a variety of derisive terms directed against doctors (e.g.,"M.D. stands for "minor deity" or "more drugs"), many of which highlight doctors' tendency to believe they are right and an extreme dislike of being challenged.

This I would argue is due to:

•Our deification of experts and particularly doctors (to support the social hierarchy) tends to inflate one's ego and reduce their willingness to listen to dissenting voices.

•Due to the selection process, doctors often tend to be more in their heads than their hearts—which makes it more challenging to acknowledge when one is wrong, don't know something, or listen to a struggling patient whose experience challenges one's existing world view.

•The training process is quite grueling, and per the principle of cognitive dissonance, creates a psychological investment in doctors where they believe what they learned must have immense value.

•Medical training (particularly the extended sleep deprivation) tends to strongly ingrain what one is taught into them and burn out one's nervous system, while in parallel, the demands of medical practice (e.g., more and more charts) tend to reduce the time they have to learn. Because of this, I frequently find doctors are mentally burned out, so it's difficult for them to learn new information or shift deeply ingrained viewpoints.

•There is so much to learn in medicine, it's impossible for anyone to ever know all of it and I am constantly learning new things (which are sometimes paradigm shifting) on a daily basis. To "address this," I (and likely many other doctors) was told throughout my training that patients expect us to "know" the answer to feel secure, was repeatedly reprimanded for doing the opposite. As a result, I repeatedly saw my co-residents give answers I knew they had no basis for (and in numerous cases I believed were wrong). Fortunately, I believe the profession is going to be forced to change this soon, as AI systems can rapidly find answers to these less common questions doctors do not know, and in theory, force the profession to become more humble once they see over and over that their patients know more about the diseases than they do and are no longer "trusting their credibility."

Note: I have an aptitude for learning and retaining information (largely due to an endless curiosity and figuring out to use the sleep cycle to facilitate rapid, long-term retention of information), and for decades I've constantly studied so many different aspects of conventional and natural medicine (along with assembling a network of colleagues whom I know to query for specific questions). Despite all of this, there is a lot I don't know, and I've had many times I admitted to patients I didn't know the answer to their question and only have a best guess (which surprises them and makes them trust me more as they've never heard another doctor say that).

•Having dominion over the body and knowing the causes of disease and treating them with pharmaceutical drugs are foundational to a doctor's identity (as without that, they often have little to show for their degree). Because of this, when a patient doesn't want to take a doctor's prescription or questions their advice, this is often seen as an attack on their identity—and when people's identities are threatened, their normal coping mechanism is denial and getting very hostile to the offending party (particularly if there is culpability on the doctor's part for injuring a patient with a pharmaceutical).

Note: many patients I know who were severely injured from pharmaceutical had a strong intuition to not take it, but eventually gave in due to the doctor relentlessly badgering them (and in turn, they consider not doing so to be one of the greatest regrets of their life). For that reason I wrote a much more detailed article on why doctors tend to push pharmaceuticals on patients.

•The medical field tends to be rather prone to a herd-mentality (in part because breaking from it is severely reprimanded both during their training and while in practice, and also because aligning with the orthodoxy supports a physician's sense of identity). Because of this, I tend to see doctors all say rather hateful things towards patients who break from an orthodoxy (e.g., I saw medical students and doctors say patients who don't vaccinate deserve to die)—despite medical training officially telling doctors it is critical to have respect for patients with views and lifestyle choices they significantly disagree with.

Note: Doctor Miller made an excellent point—doctors did not want to treat unvaccinated patients despite it being well accepted in medicine that you should treat trauma patients with AIDS regardless of the potential risk a surgeon is exposed to. The key difference between these two cases is that the unvaccinated violated a current medical taboo.

Institutional Cycles

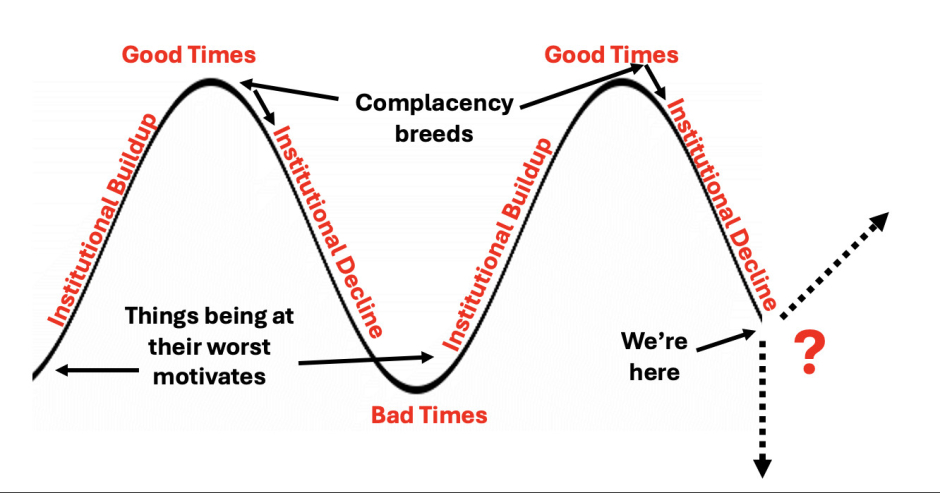

Many individuals throughout history have observed societies tend to go through of periods of institutional build up and institutional decline, due hard times motivating everyone to prioritize doing what they can to make things work, while easy times (due to the work done during the times) giving way to greed and complacency followed by laziness and entitlement, intellectualism, decadence, internal strife, and eventually a societal collapse (e.g., this is why Empires typically only last seven generations).

Briefly, this is how I would describe this equilibrium:

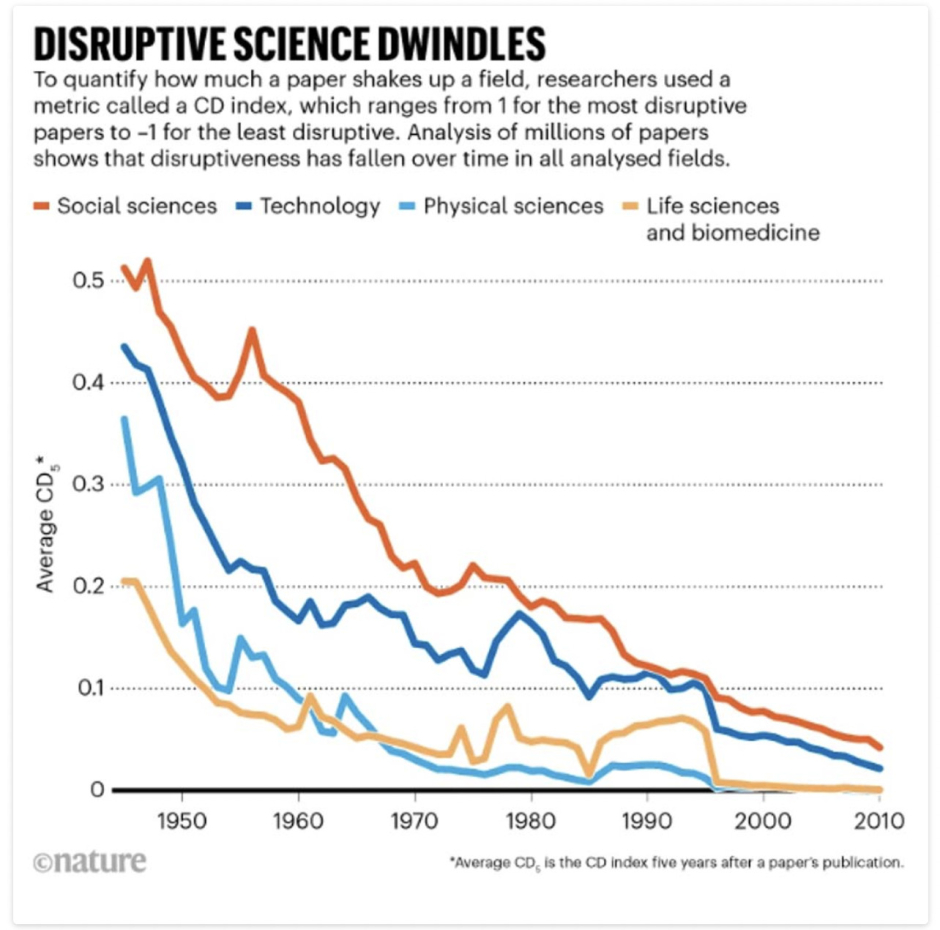

While I ascribe to this theory, I also think it holds true at much smaller scales, and accurately describes what has happened with science, where the discipline used to be largely conducted through self-investment, whereas it gained popularity and funding, it became transformed into whatever received the most public or private funding (e.g., nothing which disrupts the status quo).

The above study in turn is frequently cited to explain why science is producing far fewer useful ideas which completely upturn existing paradigms and create new fields of science which can advance society. Likewise, I believe this helps to explain why so many remarkable medical inventions emerged in America in the first half of the 1900s, as this was a time where technology had developed enough to create them, but the systems of controls (cutting off vital funding or having the government blacklist the therapy) were not yet fully entrenched in the society.

As such, while the scientific community continuously laments how much losses of funding is "hurting America" I believe the actual issue is that our money isn't being spent on things which can actually help country, and that both cuts and a better prioritization of research dollars will likely help the country.

Note: Jay Buttacharia is attempting to address this with a variety of innovative policies which hopefully will begin addressing this mess.

Conclusion

As I've tried to show here, I believe the doctor response Calley Means discussed is due to:

•Doctors not having enough time to give comprehensive care to patients (or being willing to sacrifice the income that would require).

•Doctors not having the training to know how to cure their patient's ailments (e.g., pharmacology tends to diagnose and treat by symptoms rather than cause).

•A tendency in medicine to ridicule any approach to medicine that challenges the authority and knowledge of medicine and the doctor, combined with the egotistical traits fostered by a medical education.

On one hand, as Calley's post shows, I am overjoyed we are beginning to shift the public consciousness on this, and, at last, after a century, bring things back into equilibrium. However, I am also concerned as:

•Frequently conventional medical care is necessary. For example, I know a few well-renowned natural doctors who missed a common emergent-medical diagnosis and would have seriously injured or killed their patient had the patient not subsequently decided to go to the ER. Likewise, I know a famous natural medicine doctor who had an easily treatable illness who fearfully refused to go to the hospital and only came in on the verge of death where nothing could be done (and died shortly after).

•Many medical services are essential and difficult to replicate without a vast infrastructure behind them.

•A lot of work went into creating the health apparatus we have, and many of our best and brightest and best trained are in it. As such, were it to be scrapped, it would be an immense waste of the social investment put into it and there is nothing to replace it.

•Alternative medicine is a "wild west" and while I know many excellent people in the field, I also know a lot of either clueless or predatory people in it. As such, entirely switching over to it would also cause a lot of people to have bad outcomes they were not prepared for.

At the same time, there are many excellent and well-intentioned doctors who want to practice a form of medicine which truly heals their patients, but for a variety of reasons (e.g., being trapped by the medical system) they can't, and as a result, only a small number are able to make the leap into a more integrative and natural form of medicine which incorporates their critical medical skills.

Given all of this, I believe solutions with merit include:

•There needs to be a much greater focus on learning the physical examination in medical school and (appropriately) touching and connecting with patients. In many cases, this connection is the most healing part of the interaction, and when an exam is done properly, doctors can detect things most other health professionals miss. Unfortunately, the focus on doing diagnoses via expensive imaging has caused this skill to be lost (excluding in doctors who trained in countries which could not afford the technology) and I routinely find I regularly find things everyone else missed due to a physical examination (e.g., subtle neurological signs of vaccine injuries)—which most importantly is not something AI will ever be able to automate and replace.

•Consider adding a final required board exam (after Step 3) for residents which assesses competency in lifestyle medicine, treating issues many patients chronically struggle with (that at best have perpetual management with harmful medications) and the basics of integrative medicine that parties outside the medical profession are allowed to have input on shaping. Were this to be made and required for licensure or board certification (which could be done at a federal or state level), I think it would create a cultural shift where these arts would begin to be taught in a place where there is space for them and make residents be able to first hand see the benefits of them.

•Physician reimbursement needs to shift to time spent directly with the patient.

•Physicians need more support to work independently outside a corporate system. Again and again, I hear from my readers that the doctors from that era were "better" and many of their fondest memories come from that time.

•The regulatory burdens that make it impossible for doctors to practice, particularly with insurance (and all the extra expenses they create) need to be reduced. In parallel, if this is done, the reimbursements can also be reduced without significantly deterring healthcare workers from practicing.

•As there is not enough time to learn everything in medical school, there need to be established training pathways for doctors who want to learn more once they've finished their training. I constantly hear from doctors and medical students who are desperately searching for this and many state that this publication has been that lifeblood for them. On one hand this motivates me to keep writing, but on the other, it makes me extremely concerned those options aren't out there and people instead find themselves having to rely upon an anonymous blog to find it.

•It is important we support doctors who are trying to do the right thing and make medicine better for everyone. One of the major problems is that typically when people feel compelled to do this, they are alone and vulnerable from attacks from all sides, so most stay on the sidelines as they know what happened to those who stepped out. We live in a different climate now, and need to bring the medical freedom it makes possible to the forefront.

•At the end of the day, the primary thing medicine listens to is not suffering but money, and the reason there is suddenly a concern about the loss of public trust in medicine and patients wanting alternatives is because it's costing the system money. As such, the most powerful thing we can do to fix the medical system is simply find ways to heal ourselves which bypass the existing system and cost it money.

For example, based on the direct reader feedback I've received—which likely represents a small fraction of the DMSO users I've reached, knowing the annual cost of the conditions they've successfully treated, their choice to replace costly medical care with curative DMSO has resulted in millions in lost medical sales. Furthermore, DMSO is just one of many things which can do that (although most natural therapies tend to be more disease specific).

Right now, I believe the orthodox scientific and medical community still have not come to terms with the cataclysmic societal shift their greed invoked, and as such, we are seeing them throw a fit and continue to use the same tired and old tactics (e.g., have the media demonize anyone who does anything alternative and talking down to everyone who dies). This is clearly not working, and sooner or later, they will have to change as so many forces are at last working against them.

While there was a lot of manipulation and monopolization behind the scenes (e.g., by the American Medical Association), originally, both scientists and doctors earned their credibility in our society by producing phenomenal results which changed the world. However, like all societal cycles, that caused them to get complacent and focus on money and ego, rather than continuing the pioneering spirit that allowed science to transform the world.

Because of this, it falls on us to both economically demand that change, and elevate those who are trying to fulfill that role so that the corruption and rot in science can be reverted and we can have an apparatus that truly benefits humanity. From looking at the moves made by RFK's team, I believe this is one of their key goals, and unlike everyone in the past who has tried to, they are not restrained by industries who don't want that to happen (as real science causes them to lose money and their monopolies).

However, if we indeed want that to happen, it is critical we all do what we can to create the grass roots support for it and vote with our spending dollars to make it happen. As such, I am profoundly grateful to each of you who has provided the support which has made it possible for me to engage in this endeavor and help catalyze the change and restoration our society has so sorely needed.