« La notion de développement durable implique certes des limites. Il ne s'agit pourtant pas de limites absolues mais de celles qu'imposent l'état actuel de nos techniques et de l'organisation sociale ainsi que de la capacité de la biosphère de supporter les effets de l'activité humaine.»Rapport Brudtland sur le développement durable (1987)

Note LHK: Cette publication est composée de 3 articles. Un de Futura-Science (2021), un autre de Nature, et le 3ème de The Guardian de 2012 (en anglais, il suffit d'activer la traduction en bas à droite. merci). Ne ratez pas la vidé de CNBC.

Ce projet d'injection de particules dans l'atmosphère est copieusement financé par Bill Gates dans le cadre de programmes hébergés par l'Université de Harvard nous est subitement vendu comme étant made in China. La réalité est qu'il est privé, commercial et en développement depuis de nombreuses années. La Chine est peut-être un client de M Gates?

Bref, levez vos yeux pendant votre confinement, sachant que le trafic aérien commercial a énormément chuté. LHK

L'injection de soufre dans l'atmosphère va-t-elle nous sauver du réchauffement climatique ? Futura-Science

Pour lutter contre le réchauffement climatique, tous les moyens sont bons, estiment certains. Y compris ce qu'ils appellent la géoingénierie solaire. Mais d'autres soulignent des effets indésirables qui pourraient avoir de lourdes conséquences. Slimane Bekki, chercheur au CNRS, nous aide à peser le pour et le contre de ce « plan B «

[EN VIDÉO] L'histoire du réchauffement climatique en 35 secondes En intégrant graphiquement les mesures de températures dans presque tous les pays du Globe entre 1900 et 2016, cette animation montre de façon saisissante l'augmentation du nombre d'« anomalies de température », donc des écarts par rapport à une moyenne. On constate qu'en un peu plus d'un siècle, la proportion vire au rouge.

« Injecter du soufre dans la stratosphère permet de rafraîchir la planète. Nous en sommes certains. Cela se produit naturellement lors d'éruptions volcaniques. Un an environ après l'éruption du Pinatubo (Philippines) en 1991 - qui a injecté 15-20 Mt de dioxyde de soufre dans la stratosphère -, par exemple, nous avons vu les températures moyennes mondiales baisser d'environ 0,5 °C », nous raconte Slimane Bekki, chercheur au CNRS, en introduction.

Comment ça marche ? Rappelons d'abord que la stratosphère est une région de l' atmosphère qui se situe au-dessus de 8 et 15 kilomètres d'altitude ; une région particulièrement stable sur le plan météorologique comparée à la troposphère qui se trouve en dessous, entre la surface de la Terre et la stratosphère. Ainsi dans la stratosphère, les circulations d' air sont lentes. « Le soufre, qui y est injecté, est oxydé et produit des aérosols qui y restent parfois pour des années, alors que, par comparaison, le soufre et les aérosols sont rapidement éliminés par les pluies dans la troposphère, nous fait ainsi remarquer Slimane Bekki. Les aérosols stratosphériques jouent ainsi un peu le rôle d'autant de miroirs miniatures qui diffusent le rayonnement solaire, en réfléchissant une partie vers l'espace. » De quoi refroidir efficacement la planète.

Le saviez-vous ?

Dans la catégorie géoingénierie - ou d'intervention climatique - par gestion du rayonnement solaire, on trouve d'autres technologies comme l'injection de sels marins dans les nuages. Objectif : augmenter la brillance des nuages et donc réfléchir encore de rayonnement solaire vers l'espace. L'efficacité de la technique reste toutefois incertaine.

Certains ont aussi envisagé de placer en orbite, des structures réfléchissantes. Mais le défi technologique posé par cette option et son coût exorbitant, à défaut de refroidir la planète, ont refroidi les ardeurs.

De prime abord, la technique de géoingénierie solaire - ou d'intervention climatique, comme préfère l'appeler Slimane Bekki - qui consiste à gérer le rayonnement solaire qui nous arrive en s'appuyant sur des aérosols stratosphériques apparaît donc comme la solution miracle au réchauffement climatique anthropique. Mais « il n'en est rien », nous prévient Slimane Bekki.

« Ce que certains qualifient de plan B peut tout juste être considéré comme une manière de gagner du temps. » Car les chercheurs le savent : les effets collatéraux d'une injection de particules soufrées dans la stratosphère pourraient, in fine, s'avérer plus néfastes encore que le réchauffement lui-même.

La course contre le réchauffement climatique est lancée. La géoingénierie solaire nous permettra peut-être de gagner un peu de temps si les choses devaient finalement échapper à notre contrôle. © pathdoc, Adobe Stock

Les effets indésirables de la géoingénierie solaire

Parmi les effets secondaires connus, il y a d'abord la destruction de la couche d'ozone liée à l'augmentation des aérosols stratosphériques, phénomène déjà observé après les grandes éruptions volcaniques récentes. Et l'augmentation des rayonnements ultraviolets arrivant à la surface de la Terre qui l'accompagnerait. Ce n'est évidemment pas souhaitable. Mais il y a aussi, « et peut-être même surtout, les impacts que l'opération aurait sur le cycle de l'eau et sur les précipitations, souligne le chercheur du CNRS. Les simulations montrent des modifications sévères des cycles des moussons, par exemple. Des moussons qui s'affaiblissent et se déplacent. Avec potentiellement des conséquences sur la vie de deux à trois milliards d'individus. Alors même que la question de la ressource en eau est aussi sensible que celle de la hausse des températures. Aujourd'hui déjà, les modifications du cycle de l'eau induites par le réchauffement climatique anthropique accentuent les disparités entre régions sèches et régions humides. La géoingénierie solaire va compliquer la situation. »

Ainsi régulé par géoingénierie solaire, le climat connaîtrait donc immanquablement des changements résiduels assez forts à l'échelle régionale. De quoi soulever des questions éthiques et de gouvernance assez lourdes. « À qui la décision d'intervenir ainsi sur le climat reviendra-t-elle ? Il faudra sans doute arriver à un accord international. Mais il sera difficile à trouver. Certains pays peuvent en effet considérer que le réchauffement constitue une bonne nouvelle pour eux et bloquer le processus. D'autres, qu'une telle intervention climatique serait catastrophique pour leurs ressources en eau, notamment en lien avec les moussons. »

Tout cela, sans parler du fait que la problématique du réchauffement climatique ne se limite pas à celle de la hausse des températures. « Continuer à émettre du CO2, c'est aussi poursuivre l'acidification des océans et ses effets néfastes tels que la disparition des coraux. Aujourd'hui, nous ne savons pas jusqu'où cela peut aller. Mais il apparaît évident qu'il n'est pas soutenable de laisser les concentrations de gaz à effet de serre dans notre atmosphère augmenter. »

#CLIMAT Les chercheur.e.s craignent que cette baisse des émissions ne soit passagère en raison du ralentissement économique - que les émissions mondiales de CO2 connaissent un rebond en 2021. Les données pencheraient pour cette dernière option. Mais leur niveau reste incertain. pic.twitter.com/NTfwPNFaEn- P. Saint-Julien (josephine_pstj) December 11, 2020

Ne pas perdre l'essentiel de vue

Intervenir sur le climat en injectant du soufre dans la stratosphère pourrait pourtant nous détourner dangereusement de cet objectif primordial. Et « avec l'augmentation des émissions de CO2, nous devrons injecter de plus en plus de soufre dans la stratosphère pour espérer contrecarrer la tendance au réchauffement. Or plus nous injecterons de particules, moins nous pourrons nous arrêter », prévient Slimane Bekki. Sous peine de subir ce que les chercheurs appellent un rattrapage climatique de plus en plus violent. « Un arrêt brutal des injections pourrait nous faire prendre 2 à 3 °C en une décennie seulement. »

Un risque d'autant plus difficile à envisager que de récents travaux de chercheurs américains suggèrent que l'efficacité même de la géoingénierie solaire aurait ses limites. Si nos émissions de gaz à effet de serre ne ralentissent pas, les concentrations dans l'atmosphère pourraient atteindre un niveau tel qu'elles rendraient les stratocumulus plus fins, finissant par les éliminer, même en présence de géoingénierie solaire. Or sans cette couverture nuageuse, l'injection de particules dans la stratosphère perdrait tout son intérêt."Il n'y a pas plus de plan B pour le climat que de planète B

« Cela fait un siècle, maintenant, que nous avons engagé une expérience qui peut être qualifiée de géoingénierie. Dans laquelle les Hommes modifient le climat à grande échelle ? Mais cette expérience-là n'est absolument pas délibérée.

Ce dont nous parlons ici, c'est d'intervenir de manière intentionnelle sur le climat à l'échelle globale. De l'autre côté de l'Atlantique, des sociétés privées travaillent déjà à développer les techniques de l'injection de soufre dans la stratosphère.

Mais nous pouvons tourner le problème dans tous les sens. Nous ne pouvons pas éviter de réduire nos émissions de CO2. Et quand je dis réduire, je veux dire de manière agressive. Pas de la manière marginale dont nous le faisons actuellement. Parce qu'en réalité soyez-en sûr : il n'y a pas plus de plan B pour le climat que de planète B. »

Nathalie Mayer

First sun-dimming experiment will test a way to cool Earth. Nature

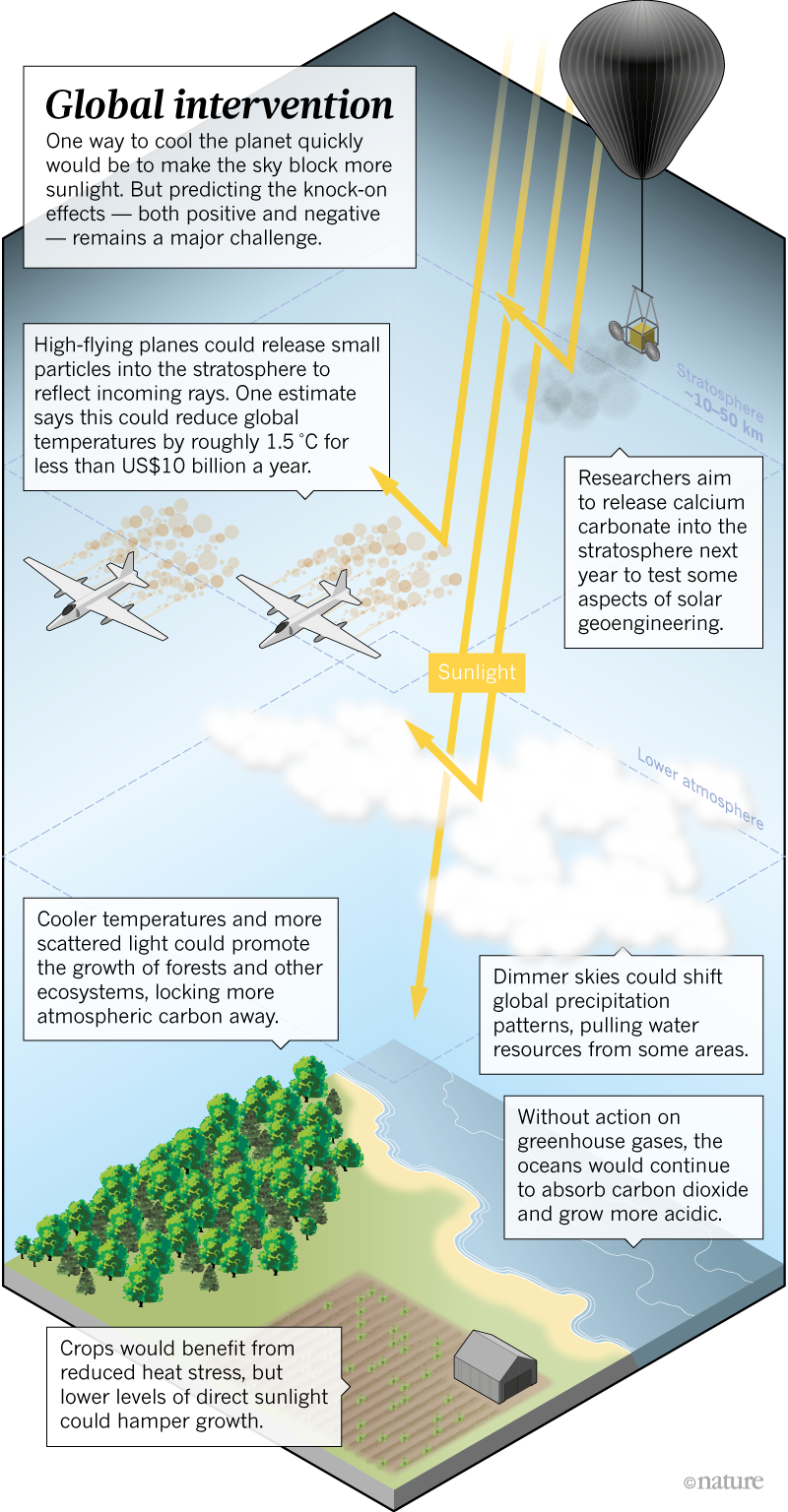

Researchers plan to spray sunlight-reflecting particles into the stratosphere, an approach that could ultimately be used to quickly lower the planet's temperature.

Zhen Dai holds up a small glass tube coated with a white powder: calcium carbonate, a ubiquitous compound used in everything from paper and cement to toothpaste and cake mixes. Plop a tablet of it into water, and the result is a fizzy antacid that calms the stomach. The question for Dai, a doctoral candidate at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and her colleagues is whether this innocuous substance could also help humanity to relieve the ultimate case of indigestion: global warming caused by greenhouse-gas pollution.

The idea is simple: spray a bunch of particles into the stratosphere, and they will cool the planet by reflecting some of the Sun's rays back into space. Scientists have already witnessed the principle in action. When Mount Pinatubo erupted in the Philippines in 1991, it injected an estimated 20 million tonnes of sulfur dioxide into the stratosphere - the atmospheric layer that stretches from about 10 to 50 kilometres above Earth's surface. The eruption created a haze of sulfate particles that cooled the planet by around 0.5 °C. For about 18 months, Earth's average temperature returned to what it was before the arrival of the steam engine.

The idea that humans might turn down Earth's thermostat by similar, artificial means is several decades old. It fits into a broader class of planet-cooling schemes known as geoengineering that have long generated intense debate and, in some cases, fear.

Researchers have largely restricted their work on such tactics to computer models. Among the concerns is that dimming the Sun could backfire, or at least strongly disadvantage some areas of the world by, for example, robbing crops of sunlight and shifting rain patterns.

But as emissions continue to rise and climate projections remain dire, conversations about geoengineering research are starting to gain more traction among scientists, policymakers and some environmentalists. That's because many researchers have come to the alarming conclusion that the only way to prevent the severe impacts of global warming will be either to suck massive amounts of carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere or to cool the planet artificially. Or, perhaps more likely, both.

If all goes as planned, the Harvard team will be the first in the world to move solar geoengineering out of the lab and into the stratosphere, with a project called the Stratospheric Controlled Perturbation Experiment (SCoPEx). The first phase - a US$3-million test involving two flights of a steerable balloon 20 kilometres above the southwest United States - could launch as early as the first half of 2019. Once in place, the experiment would release small plumes of calcium carbonate, each of around 100 grams, roughly equivalent to the amount found in an average bottle of off-the-shelf antacid. The balloon would then turn around to observe how the particles disperse.

The test itself is extremely modest. Dai, whose doctoral work over the past four years has involved building a tabletop device to simulate and measure chemical reactions in the stratosphere in advance of the experiment, does not stress about concerns over such research. "I'm studying a chemical substance," she says. "It's not like it's a nuclear bomb."

Nevertheless, the experiment will be the first to fly under the banner of solar geoengineering. And so it is under intense scrutiny, including from some environmental groups, who say such efforts are a dangerous distraction from addressing the only permanent solution to climate change: reducing greenhouse-gas emissions. The scientific outcome of SCoPEx doesn't really matter, says Jim Thomas, co-executive director of the ETC Group, an environmental advocacy organization in Val-David, near Montreal, Canada, that opposes geoengineering: "This is as much an experiment in changing social norms and crossing a line as it is a science experiment."

Aware of this attention, the team is moving slowly and is working to set up clear oversight for the experiment, in the form of an external advisory committee to review the project. Some say that such a framework, which could pave the way for future experiments, is even more important than the results of this one test. "SCoPEx is the first out of the gate, and it is triggering an important conversation about what independent guidance, advice and oversight should look like," says Peter Frumhoff, chief climate scientist at the Union of Concerned Scientists in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and a member of an independent panel that has been charged with selecting the head of the advisory committee. "Getting it done right is far more important than getting it done quickly."

Joining forces

In many ways, the stratosphere is an ideal place to try to make the atmosphere more reflective. Small particles injected there can spread around the globe and stay aloft for two years or more. If placed strategically and regularly in both hemispheres, they could create a relatively uniform blanket that would shield the entire planet (see 'Global intervention'). The process does not have to be wildly expensive; in a report last month, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change suggested that a fleet of high-flying aircraft could deposit enough sulfur to offset roughly 1.5 °C of warming for around $1 billion to $10 billion per year CR1.

Most of the solar geoengineering research so far has focused on sulfur dioxide, the same substance released by Mount Pinatubo. But sulfur might not be the best candidate. In addition to cooling the planet, the aerosols generated in that eruption sped up the rate at which chlorofluorocarbons deplete the ozone layer, which shields the planet from the Sun's harmful ultraviolet radiation. Sulfate aerosols are also warmed by the Sun, enough to potentially affect the movement of moisture and even alter the jet stream. "There are all of these downstream effects that we don't fully understand," says Frank Keutsch, an atmospheric chemist at Harvard and SCoPEx's principal investigator.

The SCoPEx team's initial stratospheric experiments will focus on calcium carbonate, which is expected to absorb less heat than sulfates and to have less impact on ozone. But textbook answers - and even Dai's tabletop device - can't capture the full picture. "We actually don't know what it would do, because it doesn't exist in the stratosphere," Keutsch says. "That sets up a red flag."

SCoPEx aims to gather real-world data to sort this out. The experiment began as a partnership between atmospheric chemist James Anderson of Harvard and experimental physicist David Keith, who moved to the university in 2011. Keith has been investigating a variety of geoengineering options off and on for more than 25 years. In 2009, while at the University of Calgary in Canada, he founded the company Carbon Engineering, in Squamish, which is working to commercialize technology to remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

After joining Harvard, Keith used research funding he had received from Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates, to begin planning the experiment.

Keutsch, who got involved later, is not a climate scientist and is at best a reluctant geoengineer. But he worries about where humanity is heading, and what that means for his children's future. When he saw Keith talk about the SCoPEx idea at a conference after starting at Harvard in 2015, he says his initial reaction was that the idea was "totally insane". Then he decided it was time to engage. "I asked myself, an atmospheric chemist, what can I do?" He joined forces with Keith and Anderson, and has since taken the lead on the experimental work.

An eye on the sky

Already, SCoPEx has moved farther along than earlier solar geoengineering efforts. The UK Stratospheric Particle Injection for Climate Engineering experiment, which sought to spray water 1 kilometre into the atmosphere, was cancelled in 2012 in part because scientists had applied for patents on an apparatus that could ultimately affect every human on the planet. (Keith says there will be no patents on any technologies involved in the SCoPEx project.) And US researchers with the Marine Cloud Brightening Project, which aims to spray saltwater droplets into the lower atmosphere to increase the reflectivity of ocean clouds, have been trying to raise money for the project for nearly a decade.

Although SCoPEx could be the first solar geoengineering experiment to fly, Keith says other projects that have not branded themselves as such have already provided useful data. In 2011, for example, the Eastern Pacific Emitted Aerosol Cloud Experiment pumped smoke into the lower atmosphere to mimic pollution from ships, which can cause clouds to brighten by capturing more water vapour. The test was used to study the effect on marine clouds, but the results had a direct bearing on geoengineering science: the brighter clouds produced a cooling effect 50 times greater than the warming effect of the carbon emissions from the researchers'ship CR2.

Keith says that the Harvard team has yet to encounter public protests or any direct opposition - aside from the occasional conspiracy theorist. The challenge facing researchers, he says, stems more from a fear among science-funding agencies that investing in geoengineering will lead to protests by environmentalists.

To help advance the field, Keith set a goal in 2016 of raising $20 million to support a formal research programme that would cover not just the experimental work, but also research into modelling, governance and ethics. He has raised around $12 million so far, mostly from philanthropic sources such as Gates; the pot provides funding to dozens of people, largely on a part-time basis.

Keith and Keutsch also want an external advisory committee to review SCoPEx before it flies. The committee, which is still to be selected, will report to the dean of engineering and the vice-provost for research at Harvard. "We see this as part of a process to build broader support for research on this topic," Keith says.

Keutsch is looking forward to having the guidance of an external group, and hopes that it can provide clarity on how tests such as his should proceed. "This is a much more politically challenging experiment than I had anticipated," he says. "I was a little naive."

SCoPEx faces technical challenges, too. It must spray particles of the right size: the team calculates that those with a diameter of about 0.5 micrometres should disperse and reflect sunlight well. The balloon must also be able to reverse its course in the thin air so that it can pass through its own wake. Assuming the team is able to find the calcium carbonate plume - and there is no guarantee that they can - SCoPEx needs instruments that can analyse the particles and, it is hoped, carry samples back to Earth.

"It's going to be a hard experiment, and it may not work," says David Fahey, an atmospheric scientist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration in Boulder, Colorado. In the hope that it will, Fahey's team has provided SCoPEx with a lightweight instrument that can reliably measure the size and number of particles that are released. The balloon will also be equipped with a laser device that can monitor the plume from afar. Other equipment that could collect information on the level of moisture and ozone in the stratosphere could fly on the balloon as well.

Up to the stratosphere

Keutsch and Keith are still working out some of the technical details. Plans with one balloon company fell through, so they are now working with a second. And an independent team of engineers in California is working on options for the sprayer. To simplify things, the SCoPEx group plans to fly the balloon during the spring or autumn, when stratospheric winds shift direction and - for a brief period - calm down, which will make it easier to track the plume.

For all of these reasons, Keutsch characterizes the first flight as an engineering test, mainly intended to demonstrate that everything works as it should. The team is ready to spray calcium carbonate particles, but could instead use salt water to test the sprayer if the advisory committee objects.

Keith still thinks that sulfate aerosols might ultimately be the best choice for solar geoengineering, if only because there has been more research about their impact. He says that the possibility of sulfates enhancing ozone depletion should become less of a concern in the future, as efforts to restore the ozone layer through pollutant reductions continue. Nevertheless, his main hope is to establish an experimental programme in which scientists can explore different aspects of solar geoengineering.

There are a lot of outstanding questions. Some researchers have suggested that solar geoengineering could alter precipitation patterns and even lead to more droughts in some regions. Others warn that one of the possible benefits of solar geoengineering - maintaining crop yields by protecting them from heat stress - might not come to pass. In a study published in August, researchers found that yields of maize (corn), soya, rice and wheat CR3 fell after two volcanic eruptions, Mount Pinatubo in 1991 and El Chichón in Mexico in 1982, dimmed the skies. Such reductions could be enough to cancel out any potential gains in the future.

Keith says the science so far suggests that the benefits could well outweigh the potential negative consequences, particularly compared with a world in which warming goes unchecked. The commonly cited drawback is that shielding the Sun doesn't affect emissions, so greenhouse-gas levels would continue to rise and the ocean would grow even more acidic. But he suggests that solar geoengineering could reduce the amount of carbon that would otherwise end up in the atmosphere, including by minimizing the loss of permafrost, promoting forest growth and reducing the need to cool buildings. In an as-yet-unpublished analysis of precipitation and temperature extremes using a high-resolution climate model, Keith and others found that nearly all regions of the world would benefit from a moderate solar geoengineering programme. "Despite all of the concerns, we can't find any areas that would be definitely worse off," he says. "If solar geoengineering is as good as what is shown in these models, it would be crazy not to take it seriously."

There is still widespread uncertainty about the state of the science and the assumptions in the models - including the idea that humanity could come together to establish, maintain and then eventually dismantle a well-designed geoengineering programme while tackling the underlying problem of emissions. Still, prominent organizations, including the UK Royal Society and the US National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, have called for more research. In October, the academies launched a project that will attempt to provide a blueprint for such a programme.

Some organizations are already trying to promote discussions among policymakers and government officials at the international level. The Solar Radiation Management Governance Initiative is holding workshops across the global south, for instance. And Janos Pasztor, who handled climate issues under former UN secretary-general Ban Ki-moon, has been talking to high-level government officials around the world in his role as head of the Carnegie Climate Geoengineering Governance Initiative, a non-profit organization based in New York. "Governments need to engage in this discussion and to understand these issues," Pasztor says. "They need to understand the risks - not just the risks of doing it, but also the risks of not understanding and not knowing."

One concern is that governments might one day panic over the consequences of global warming and rush forward with a haphazard solar-geoengineering programme, a distinct possibility given that the costs are cheap enough that many countries, and perhaps even a few individuals, could probably afford to go it alone. These and other questions arose earlier this month in Quito, Ecuador, at the annual summit of the Montreal Protocol, which governs chemicals that damage the stratospheric ozone layer. Several countries called for a scientific assessment of the potential effects that solar geoengineering could have on the ozone layer, and on the stratosphere more broadly.

If the world gets serious about geoengineering, Fahey says that there are plenty of sophisticated experiments that researchers could do using satellites and high-flying aircraft. But for now, he says, SCoPEx will be valuable - if only because it pushes the conversation forward. "Not talking about geoengineering is the greatest mistake we can make right now."

- 1.Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Global Warming of 1.5 °C (IPCC, 2018).

- 2.Russell, L. M. et al. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 94, 709-729 (2013).

- 3.Proctor, J., Hsiang, S., Burney, J., Burke, M. & Schlenker, W. Nature 560, 480-483 (2018)

https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-018-07533-4

Bill Gates backs climate scientists lobbying for large-scale geoengineering

This article is more than 8 years oldOther wealthy individuals have also funded a series of reports into the future use of technologies to geoengineer the climate

• What is geo-engineering?

• Scientists criticise handling of geoengineering pilot project

The billionaire philanthropist Bill Gates is backing a group of climate scientists lobbying for geoengineering experiments.Photograph: Ted S. Warren/AP John Vidal, environment editiorMon 6 Feb 2012 10.18 GMT

A small group of leading climate scientists, financially supported by billionaires including Bill Gates, are lobbying governments and international bodies to back experiments into manipulating the climate on a global scale to avoid catastrophic climate change.

The scientists, who advocate geoengineering methods such as spraying millions of tonnes of reflective particles of sulphur dioxide 30 miles above earth, argue that a « plan B » for climate change will be needed if the UN and politicians cannot agree to making the necessary cuts in greenhouse gases, and say the US government and others should pay for a major programme of international research.

Solar geoengineering techniques are highly controversial: while some climate scientists believe they may prove a quick and relatively cheap way to slow global warming, others fear that when conducted in the upper atmosphere, they could irrevocably alter rainfall patterns and interfere with the earth's climate.

Geoengineering is opposed by many environmentalists, who say the technology could undermine efforts to reduce emissions, and by developing countries who fear it could be used as a weapon or by rich countries to their advantage. In 2010, the UN Convention on Biological Diversity declared a moratorium on experiments in the sea and space, except for small-scale scientific studies.

Concern is now growing that the small but influential group of scientists, and their backers, may have a disproportionate effect on major decisions about geoengineering research and policy.

« We will need to protect ourselves from vested interests [and] be sure that choices are not influenced by parties who might make significant amounts of money through a choice to modify climate, especially using proprietary intellectual property, » said Jane Long, director at large for the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in the US, in a paper delivered to a recent geoengineering conference on ethics.

« The stakes are very high and scientists are not the best people to deal with the social, ethical or political issues that geoengineering raises, » said Doug Parr, chief scientist at Greenpeace. « The idea that a self-selected group should have so much influence is bizarre. »

Pressure to find a quick technological fix to climate change is growing as politicians fail to reach an agreement to significantly reduce emissions. In 2009-2010, the US government received requests for over $2bn(£1.2bn) of grants for geoengineering research, but spent around $100m.

As well as Gates, other wealthy individuals including Sir Richard Branson, tar sands magnate Murray Edwards and the co-founder of Skype, Niklas Zennström, have funded a series of official reports into future use of the technology. Branson, who has frequently called for geoengineering to combat climate change, helped fund the Royal Society's inquiry into solar radiation management last year through his Carbon War Room charity. It is not known how much he contributed.

Professors David Keith, of Harvard University, and Ken Caldeira of Stanford, [see footnote] are the world's two leading advocates of major research into geoengineering the upper atmosphere to provide earth with a reflective shield. They have so far received over $4.6m from Gates to run the Fund for Innovative Climate and Energy Research (Ficer). Nearly half Ficer's money, which comes directly from Gates's personal funds, has so far been used for their own research, but the rest is disbursed by them to fund the work of other advocates of large-scale interventions.

According to statements of financial interests, Keith receives an undisclosed sum from Bill Gates each year, and is the president and majority owner of the geoengineering company Carbon Engineering, in which both Gates and Edwards have major stakes - believed to be together worth over $10m.

Another Edwards company, Canadian Natural Resources, has plans to spend $25bn to turn the bitumen-bearing sand found in northern Alberta into barrels of crude oil. Caldeira says he receives $375,000 a year from Gates, holds a carbon capture patent and works for Intellectual Ventures, a private geoegineering research company part-owned by Gates and run by Nathan Myhrvold, former head of technology at Microsoft.

According to the latest Ficer accounts, the two scientists have so far given $300,000 of Gates money to part-fund three prominent reviews and assessments of geoengineering - the UK Royal Society report on Solar Radiation Management, the US Taskforce on Geoengineering and a 2009 report by Novin a science thinktank based in Santa Barbara, California. Keith and Caldeira either sat on the panels that produced the reports or contributed evidence. All three reports strongly recommended more research into solar radiation management.

The fund also gave $600,000 to Phil Rasch, chief climate scientist for the Pacific Northwest national laboratory, one of 10 research institutions funded by the US energy department.

Rasch gave evidence at the first Royal Society report on geoengineering 2009 and was a panel member on the 2011 report. He has testified to the US Congress about the need for government funding of large-scale geoengineering. In addition, Caldeira and Keith gave a further $240,000 to geoengineering advocates to travel and attend workshops and meetings and $100,000 to Jay Apt, a prominent advocate of geoengineering as a last resort, and professor of engineering at Carnegie Mellon University. Apt worked with Keith and Aurora Flight Sciences, a US company that develops drone aircraft technology for the US military, to study the costs of sending 1m tonnes of sulphate particles into the upper atmosphere a year.

Analysis of the eight major national and international inquiries into geoengineering over the past three years shows that Keith and Caldeira, Rasch and Prof Granger Morgan the head of department of engineering and public policy at Carnegie Mellon University where Keith works, have sat on seven panels, including one set up by the UN. Three other strong advocates of solar radiation geoengineering, including Rasch, have sat on national inquiries part-funded by Ficer.

« There are clear conflicts of interest between many of the people involved in the debate, » said Diana Bronson, a researcher with Montreal-based geoengineering watchdog ETC.

« What is really worrying is that the same small group working on high-risk technologies that will geoengineer the planet is also trying to engineer the discussion around international rules and regulations. We cannot put the fox in charge of the chicken coop. »

« The eco-clique are lobbying for a huge injection of public funds into geoengineering research. They dominate virtually every inquiry into geoengineering. They are present in almost all of the expert deliberations. They have been the leading advisers to parliamentary and congressional inquiries and their views will, in all likelihood, dominate the deliberations of the UN's Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) as it grapples for the first time with the scientific and ethical tangle that is climate engineering, » said Clive Hamilton, professor of Public Ethics at the Australian National University, in a Guardian blog.

The scientists involved reject this notion. « Even the perception that [a small group of people has] illegitimate influence [is] very unhealthy for a technology which has extreme power over the world. The concerns that a small group [is] dominating the debate are legitimate, but things are not as they were, » said Keith. « It's changing as countries like India and China become involved. The era when my voice or that of a few was dominant is over. We need a very broad debate. »

« Every scientist has some conflict of interest, because we would all like to see more resources going to study things that we find interesting, » said Caldeira. « Do I have too much influence? I feel like I have too little. I have been calling for making CO2 emissions illegal for many years, but no one is listening to me. People who disagree with me might feel I have too much influence. The best way to reduce my influence is to have more public research funds available, so that our funds are in the noise. If the federal government played the role it should in this area, there would be no need for money from Gates.

« Regarding my own patents, I have repeatedly stated that if any patent that I am on is ever used for the purposes of altering climate, then any proceeds that accrue to me for this use will be donated to nonprofit NGOs and charities. I have no expectation or interest in developing a personal revenue stream based upon the use of these patents for climate modification. ».

Rasch added: « I don't feel there is any conflict of interest. I don't lobby, work with patents or intellectual property, do classified research or work with for-profit companies. The research I do on geoengineering involves computer simulations and thinking about possible consequences. The Ficer foundation that has funded my research tries to be transparent in their activities, as do I. »

• This article was amended on 8 February 2012. The original stated that Phil Rasch worked for Intellectual Ventures. This has been corrected. This article was further amended on 13 February 2012. Prof Caldeira has asked us to make clear that the fact that he advocates research into geoengineering does not mean he advocates geoengineering.

theguardian.com/2012/feb/06/bill-gates-climate-scientists-geoengineering

RAPPELS Visuel de l'AFP

Vidéo de Géoingénierie