President Joe Biden wants to lecture other countries to make huge commitments to combat climate change while he brings a poor U.S. record to the Glasgow conference, writes Joe Lauria.

By Joe LAURIA

President Joe Biden is at the Glasgow climate summit, carrying with him a 30-year U.S. history of presidents and Congress having taken halting measures to combat the growing threat of climate change. As the world's second largest emitter of climate-change causing greenhouse gases, the U.S. has fallen woefully short.

Starting in 1992, Congress has passed or considered only 13 major pieces of legislation in regard to global warming.

The first step by Congress was in 1992 to ratify the U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change, which committed parties to take action against global warming and prepare the ground for future agreements. In signing the treaty, then U.S. President George H.W. Bush said, "The United States fully intends to be the world's pre-eminent leader in protecting the global environment."

But the history since that has been anything but. It started out promisingly enough. That same year, Congress added a renewable energy production tax credit to the 1992 Energy Policy Act, which proved critical in expanding electricity production through wind turbines.

However, five years later the U.S. Senate blocked participation of the U.S. in the 1997 Kyoto agreement with a non-binding resolution saying the U.S. should not enter any agreement unless developing countries were held to the same level of commitment to reduce emissions. The resolution also said the U.S. should stay clear of agreements that "would result in serious harm to the economy of the United States..."

It was unrealistic to hold developing countries to the same standards as the big emitters, like the U.S., which have been spewing climate changing gases into the atmosphere since the Industrial Revolution. The U.N. Framework Agreement calls for developed nations to pay the developing world, from which many resources that made industrialism possible were stolen, to allow them to develop in an environmentally sustainable way.

In other words, the countries that became rich off the land of the poor nations, need to pay restitution in the form of allowing industrialization in the global south to proceed in a way that doesn't depend on fossil fuels. So far the industrialized north has fallen far short of providing the agreed U.N. target of $100 billion annually from 2020 to the south.

W. Blocks Kyoto

Sunlight through clouds and lookout view of Ginkaku-ji (Temple of the Silver Pavilion) and T?gud? from above, Kyoto, Japan. (Basile Morin/Wikimedia Commons)

Despite the 1997 Senate resolution that blocked participation in the Kyoto Protocol, the Bill Clinton administration signed it. But it was never sent to the Senate for ratification. In 2001, President George W. Bush said the U.S. wouldn't join the protocol. It has never been binding on the U.S.

Between 2003 and 2007 Congress three times tried to pass the Climate Stewardship Act of 2003 but failed each time. The Act would have introduced a mandatory cap and trade system for greenhouse gases from the electricity, transportation and manufacturing sectors, making up 85 percent of U.S. emissions.

In 2007, Congress at least established a Greenhouse Gas Reporting Program, which requires various economic sectors to report annual amounts of carbon dioxide emissions.

With the election of Barack Obama as president in 2008, a comprehensive climate and energy bill was sent to Congress by the White House. The House of Representatives passed the American Clean Energy and Security Act of 2009 by just seven votes, but it was not passed by the Senate. The failed Act would have created a cap-and-trade system of greenhouse gases across the U.S. economy.

Four other major pieces of legislation introduced in Congress in 2009 and 2010, which would have included a cap on emissions, failed to become law.

These bills were defeated for the most part by Republican legislators whose major concern was the effect on profits for the energy sector. A number of Republican lawmakers openly expressed their disbelief that human activity causes climate change.

What the US People Say

People vs. Fossil Fuels protest, White House, Oct. 12, 2021. (Frypie/Wikimedia Commons)

Sixty percent of U.S. people think that oil companies are to blame for global warming and want them to be held to account for lying about it, according to a poll released last week.

The respondents were split between Democrats and Republicans, with 89 percent of the former saying climate change is real, while only 42 percent of Republicans believe it is. Thirty-six percent of Republicans deny climate change, according to the poll conducted by YouGov for The Guardian, Vice News, and Covering Climate Now.

Overall, 70 percent of Americans accept global warming and 60 percent said oil and gas companies were "completely or mostly responsible" for it.

Three times more Democrats than Republicans said oil and gas companies lied about the existence of climate change and their part in creating it. Just under half of Republicans surveyed said oil and gas companies had done nothing wrong. In all, 45 percent of Americans said oil and gas firms lied about causing climate change and should be held to account.

The U.S. population in general is three times more likely to deny climate change than many other countries, such as Britain and Japan. A recent survey of climate scientists showed that 99.9 percent agreed that global warming is caused by human activity.

Congress's Continually Sputtering Efforts

U.S. Capitol. (Johnny Silvercloud/Flickr)

In 2012, a Clean Energy Standard Act was introduced in Congress but it has never gone to a floor vote.

Four years later, a Climate Solutions Caucus was formed in the House of Representatives to educate House members on "economically-viable options to reduce climate risk and protect our nation's economy, security, infrastructure, agriculture, water supply and public safety." It was the first caucus of its kind after 20 years of Congress engaging in climate policy.

After Democrats regained control of the House in 2019, a number of climate initiatives were announced, including a Green New Deal resolution in both houses (which has so not come close to passage) and the formation of a Select Committee on the Climate Crisis in the House, which issued a major report on policy recommendations.

The Senate in 2019 also created its first Climate Solutions Caucus. It took them 29 years from Congress' first climate action.

And it took until December 2020 for Congress to pass its first major climate package in 13 years. It includes tax credits and directs the Environmental Protection Agency to make phased reductions of hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) over a 15-year period.

Biden has introduced a bill in Congress this year that would spend $555 billion on ambitious climate change policies, but it is being held up by a single Democratic senator as Biden addresses the Glasgow climate summit.

Empty-Handed in Glasgow

(Pacific Community)

Biden arrived at the global climate summit in Glasgow lacking Congressional approval of his ambitious $555 billion climate bill that could undermine his effectiveness in persuading other world leaders to take serious action to prevent a looming climate catastrophe.

Biden's plan includes grants, tax cuts and other policies aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions that cause climate change, which Biden has called an "existential threat."

The money would make it easier for Americans to buy electric cars, build wind turbines, and install solar panels. Key reforms of the electric industry to the tune of $150 billion were stripped out of the bill by Senator Joe Manchin (D-WV), a rebel within Biden's party who has held up numerous legislative initiatives from the White House.

With the Senate evenly split 50-50 between Democrats and Republicans every Democratic vote is essential to pass Biden's legislation. As Aaron White wrote in an article republished in Consortium News on Oct. 24, "Manchin made $500,000 last year from a coal company owned by his son and takes in more fossil fuel cash than any other senator."

The lack of congressional support for his climate agenda is bound to increase skepticism of other world leaders when Biden tries to convince them in Glasgow to commit to zero net emissions by the year 2050. Scientists say the earth's temperature cannot rise above 2.0 degrees by then to avoid catastrophe. The Glasgow summit is being portrayed by some climate scientists as humanity's last hope.

As the world's second largest emitter of greenhouse gases, failure by the U.S. to make binding commitments to reduce those gases in domestic legislation makes it harder for Biden to convince other larger emitters, like China and India, to make similar commitments. Biden has acknowledged that "the prestige of the United States is on the line" in Scotland.

The Glasgow conference is being seen as the most important climate summit since Paris in 2015. Then U.S. President Barack Obama signed the accord committing the U.S. to reductions, but the agreement is not legally binding on signatories, the way domestic U.S. legislation is.

Former President Donald Trump pulled the U.S. out of the Paris accord. Biden, who has focused on climate policy more than any of his predecessors (his legislation is six times greater than Obama's climate initiative), is seeking to overcome Trump's policies. He has signed numerous executive orders restoring climate policies that Trump removed through his own executive orders.

But a president is limited in what reforms he can make through such orders and needs Congress to pass massive climate policies, such as the $555 billion bill. With that legislation passed, the U.S. could reduce its emissions by 50 percent over nine years in relation to 2005 levels, according to the White House.

Executive Orders

Biden signing an executive order. (White House Photo)

Since 2009, U.S. presidents have signed executive orders on climate change policy that did not require action by Congress. Obama issued 263 executive orders in his eight years in office, with 35 of them related to climate change. Many of these orders helped the individual 50 states to institute their own climate policies.

When Trump became president in 2017, he quickly reversed Obama's orders with executive orders of his own. He killed six Obama climate orders in one day within two months of becoming president. "With today's executive action, I am taking historic steps to lift the restrictions on American energy, to reverse government intrusion and to cancel job-killing regulations," Trump said that day in March 2017.

Trump had come into office vowing to help the coal and oil and gas industries, which were regulated by the Obama measures, and who heavily lobby Congress. The profit motive of the fossil fuel industry is literally choking the world and making it harder for other big emitters to undertake commitments the U.S. refuses to make.

One of the Obama measures Trump reversed was the 2015 plan to limit carbon emissions from power plants. It had set the goal of reducing its 2005 levels by 32 percent by the year 2030.

Trump also pulled the U.S. out of the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement. Within days of Biden becoming president, Biden rejoined the Paris accord, stopped drilling for oil in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge and canceled the Keystone Pipeline. He also overturned Trump's climate executive orders.

The U.S. Record

Overall, critics have found that the U.S. has had an underwhelming record when it comes to fighting climate change, a country with a special responsibility as the second greatest emitter of greenhouse gases.

Yale University's Environmental Performance Index (EPI) lists the U.S. as the 24th greenest country in the world. Denmark, Luxembourg and Switzerland are the top three. China, the world's largest emitter, is no. 120 on the list.

According to the Climate Action Tracker, produced by Climate Analytics and the New Climate Institute, the United States has an overall climate rating of "insufficient." It is found to be "critically insufficient" on climate financing. Its information on the 2050 net zero target is rated as "incomplete." U.S. emissions reductions targets are rated as not making up its fair share globally.

The overall U.S. rating has improved since Biden came to office from "critically insufficient."

A Flat Historical Trend

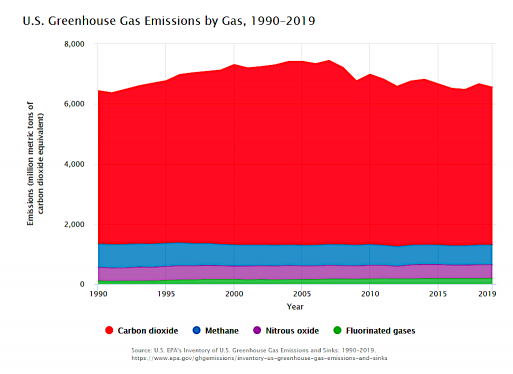

A look at U.S. carbon dioxide emissions over the past 30 years shows that from a rise of about 6,100 metric tons a year in 1990, to a peak of more than 7,000 metric tons in 2007, 2019 levels lowered to around 6,100 metric tons.

That means that over 30 years there has been no meaningful change in the amount of climate changing gases that the United States puts into the atmosphere.

It is an unconvincing and dangerous record for the exceptional nation.