By Gregg Stanley

August 9, 2022

Seventy-seven years ago, August 9th 1945, Nagasaki was nuked by the most powerful nuclear bomb to incinerate and radiate a city, with Hiroshima being second and the only other city to be destroyed. Some have called this a war crime, while others have disagreed, but all understand that the exigencies of war was their motivation. And that as long as military troops or facilitates are the target, civilian casualties are regrettable but debatable product of war. But what if the civilians and not the military was the primary target of the nuclear explosion? That the military was secondary, the collateral damage in the parlance of war. Then Nagasaki as a war crime would not be debated. This is a tall case to make. The prosecutors first requirements would be easy: having the murder weapon and having the opportunity are cinches as there is ample evidence and confessing testimony. The only hurdle, and a big one at that, is to establish motivation. To establish that the civilians were the target. To establish motivation even by a preponderance of evidence is hard to do, but what really seems to make this difficult is that Nagasaki was not listed as the primary target on August 8th!

Introduction

Armageddon's original reference is to a location cited in the bible where a conclusive battle is fought. By implication it also means a change in the world. August 9th, 1945 meets these terms. The most obvious change was the dropping of nuclear bombs on Nagasaki and before that Hiroshima, ushering in a nuclear age. Other readers may recall that with the surrender of Japan the world became bi-polar in the military sense and perhaps in the mental sense as well! We will examine these changes of August 1945 and reveal new insights on those days. There are several ways a new look at history can reveal important and exciting insights. To know where to go it is good to know where you came from. Insights can come from new information, from asking childlike questions or by putting known facts together for the first time. These insights may range from "I suspected that," to "wow," to "nope."

Seeds of Hate

When the Japanese surrender document was signed aboard the battleship Missouri, the 1853 flag of Commodore Perry was there. The seeds of the war with Japan were sown in 1853 with the uninvited appearance of Commodore Perry's black fleet at Shimoda harbor. The "Hermit Kingdom," as it was deservingly called, had banned virtually all intercourse with the rest of the world, save some Dutch ships allowed at Nagasaki. Perry was ostensibly motivated by concern over shipwrecked sailors, but primarily by a desire to open mutually beneficial trade relations. He was given broad latitude, including the option of using force, and was unencumbered by diplomats. As is often the case, the first man credited in history with a discovery came in a large expedition financed by others, and it is only to be revealed in footnotes that other individuals preceded them. The Lewis and Clark expedition of a few decades earlier asked Native Americans if they had ever seen a white man. Every tribe had seen white trappers, except some natives near the continental divide, which had poor game (1). Here, Perry was preceded by Ranald McDonald, a true adventurer, who put himself ashore disguised as a shipwreck survivor, knowing full well of the penalty of death. McDonald taught English to a dozen samurai to facilitate communication with unwanted English-speaking travelers. In Perry's negotiations all of the communications were translated to Dutch first, not the first-time negotiations were unnecessarily dragged out. McDonald was released along with a dozen other less favored caged American sailors. Perry's fleet of four ships message was as quiet as a murmur of wind, but to the future Emperor of Japan, it was as loud as an atomic bomb, 'Open up trade or else!' These words drowned out other kind and endearing words, especially to the keen ears of Japanese potentates trained in two millennia of intrigue. 17,000 troops, many of them armored samurai, wearing masks, lined the shore. Perry had steam powered ships with cannons; the Samurai had steel swords and, in many cases, small squares of iron or leather armor. After negotiations, the representative of the ill Shogun, who in turn represented the reportedly powerless Emperor (defeat has a thousand fathers), succumbed to the humiliation of accepting priceless gifts, including a telegraph and a miniature train. But those in power looked at the vile barbarian footprints on the ground.

The Emperor opened up trade to the world and embraced Western ways with startling speed, all the while burning over the imprudence and shame of 1853. The scales of justice are not the same for the West and the East. Perry may have used The Golden Rule for Japan, but to the Emperor, his son and his grandson, it was a humiliation and dishonor not to be forgotten (2). Perry's visit resulted in other western countries seeking and getting visitation rights and eventually in the Meiji Restoration. These improvements in commerce, transportation and manufacturing were inspired by the West while army and naval improvements were inspired by Germany and England respectively. Following these improvements, the world was shocked by Czarist Russia's defeat by Japan in the war of 1904-5, 47 years after Perry. Japan advanced more in 47 years than any other country had in a hundred or more. The United States helped negotiate the forthcoming treaty, which gave present day Korea to Japan while leaving an independent Manchuria for future Japanese plans.

This woodblock exemplifies how many Japanese (left) saw themselves in relation to China and her Western advisers (right).

Desperate going to War, Desperate in War

To bolster Japan's diplomatic position, it signed a nonaggression pact with Stalin on April 13th, 1941, acknowledging Japanese control of Manchuco (Manchuria) and the Soviet empire's possession of Mongolia. By the fall of 1941, the Japanese government felt strangled by Western embargoes of iron, scrap steel and especially oil, instituted in response to their invasion of China (3). The embargo was considered an existential issue, the continuation of which would reduce Japan to a third-rate power. Negotiations stalled over Roosevelt's demand for Japan to leave China and Southeast Asia (formally the French colonies of Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos). When Japan agreed to this demand, a new demand for Japan to leave Manchuria followed. To the Japanese it was the height of hypocrisy for white empires to moralize over Manchuria. Roosevelt had the benefit of seeing Japan's diplomatic communications, whose encryption was broken. My opinion is that Japan did not want a war with the United States in 1941, but felt it would become a third-rate power if it capitulated. However, war in western Europe did provide opportunity for Japan. England kept sizable armies throughout the "Empire where the sun never set." France and the Netherlands also had many colonies with armies which would have been useful when Germany invaded and conquered their homelands. The United States had the Philippines. Nowhere was Japan to find oil from this club. The Dutch East Indies, present day Indonesia, had plenty of oil, but the small Dutch army took the lead of the United States and England and shut itself to Japan.

The strongest argument against Japan wanting war was the timing. From July 1941 on, Japan drew upon it's precious raw material reserves while negotiations proceeded (3). The oil storage facility at Pearl Harbor had about as much oil as all of Japan had in reserve. The monsoon season was another problem. In the Philippines, and Malaysia, the main targets, the monsoon season started in October, and November in the case of Indonesia. The actual timing could not have been much worse.

The world in 1941 was populated by empires, and empires saw raw materials as vital to survival and growth. Japan's leading strategist and sometimes tourist poker player, Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, feared this war and was aware of America's industrial might. Reportedly he said after hearing an account of his Pearl Harbor attack, "I fear all we have done is to awaken a sleeping giant and fill him with a terrible resolve." There are those who think Roosevelt wanted Pearl Harbor attacked to get the United States into war with Japan's Axis ally Germany, and that Roosevelt even knew in advance of the attack. We won't visit that lengthy controversy today.

An Ending and a Beginning

In the beginning, God said, "Let there be light." That may be how the war ended too, with the bright blinding light of an atomic explosion. Not Hiroshima, but Nagasaki. The beginning of the end may have started at the Potsdam conference. The Potsdam Declaration of July, 1945 was intentionally vague, only promising the four main islands of Japan would remain as Japan, while allowing the Allies (not yet Russia) a completely free hand in the occupation and in removing "for all time of the authority and influence of those who have deceived and misled the people of Japan into embarking on world conquest." Another restriction on Japan could be interpreted as an Allied reversal on the embargo, 'Japan shall be permitted to maintain such industries as will sustain her economy and permit the exaction of just reparations in kind, but not those which would enable her to rearm for war. To this end, access to, as distinguished from control of, raw materials shall be permitted.' The embargo led straight to Pearl Harbor and here, with caveats, free trade was given to Japan. Another curious aspect was Truman's request that Stalin break the non-aggression treaty he had signed with Japan. I have found no mention of Truman being embarrassed in asking Stalin to break a treaty, and no mention of Stalin in having qualms in breaking his word. The Soviet declaration of war did admit that Japan had sought Russia out to mediate a peace treaty. The declaration had a humanitarian slant to it: "...shorten the duration of the war, reduce the number of victims and facilitate the speedy restoration of universal peace." And, "this policy is the only means able to bring peace nearer, free the people from further sacrifice and suffering and give the Japanese people the possibility of avoiding the dangers and destruction suffered by Germany after her refusal to capitulate unconditionally." There was no injury to Russia mentioned, only humanitarian motivations for war. Of the over half million Japanese troops who surrendered to Russia, only half returned to Japan, most in the 1950's. This suggests casualties much greater than the atomic bombs, but this would not be the first time that Stalin's "humanitarian" efforts produced such results. There is no eternal flame, and scarce mention of these casualties in our history books.

Why did Japan surrender?

Before we dig into this, it should be understood that Japan was ready to surrender weeks earlier. This was known in decrypted communications. The disagreement was in the unconditional surrender aspect. A study by General MacArthur's Southwest Pacific Command explained, "Hanging of the Emperor to them would be comparable to the crucifixion of Christ to us. All would fight like ants." (4) Of the top U.S. generals, only George Marshel stuck with unconditional surrender. So, what caused Japan to surrender? Was it Stalin's entry into the war, or the bombing of Nagasaki? The emperor's surrender statement supports each motivation. It starts briefly with Russia, "After pondering deeply the general trends of the world and the actual conditions obtaining in Our Empire today...", but then dwells on the atomic bomb, "Moreover, the enemy has begun to employ a new and most cruel bomb, the power of which to do damage is, indeed, incalculable, taking the toll of many innocent lives. Should we continue to fight, not only would it result in an ultimate collapse and obliteration of the Japanese nation, but also it would lead to the total extinction of human civilization." (Based on Japan's inhuman treatment of prisoners of war, "human civilization" meant Japan.) The Russian invasion army had a formidable 1.7 million men, although it had few transports for a mainland invasion. These are the popular reasons historians point to for why Japan surrendered-the Russian invasion and the bomb-and they can point to both the surrender speech and the timing of surrender to support their cases, as well as the military effect of these actions. Yet both explanations miss out on the best arguments, points and facts that to my knowledge have not been put together in print before.

In August 1945 the best hope Japan had was for as Stalin would say, give humanitarian aid to the United States. Had the United States not developed the atomic bomb, a Soviet attack on the United States and England might have happened, but of course Stalin already knew about the existence of the bomb and its development from spies. It is also interesting to speculate that the reason Japanese troops surrendered so quickly to Soviet troops, when they had previously fought fanatically against U.S. troops, was that Japan was still hoping for an agreement with Russia. Japan surrendered because of the Soviet attack-not because it had a new foe, but because the hope of having a powerful ally was smashed.

Now to the Nagasaki case. A common argument was that Japan was not impressed enough to surrender with Hiroshima, so why would Nagasaki be different? Nagasaki was different. "Thin Man," the name of the Hiroshima bomb, was fueled by uranium 235, a substance the Japanese scientists thought was very difficult to gather. "Fat Man," the bomb at Nagasaki, was fueled by plutonium, a harder substance to produce and to trigger, but in much greater supply. In other words, unlike Hiroshima, after Nagasaki, Japanese scientists knew it was possible for many more bombs to come. In this argument it was Nagasaki alone that was convincing. But we have one more fascinating, shocking, but still speculative argument as to why Nagasaki ended the war.

The Strange Targeting of Nagasaki

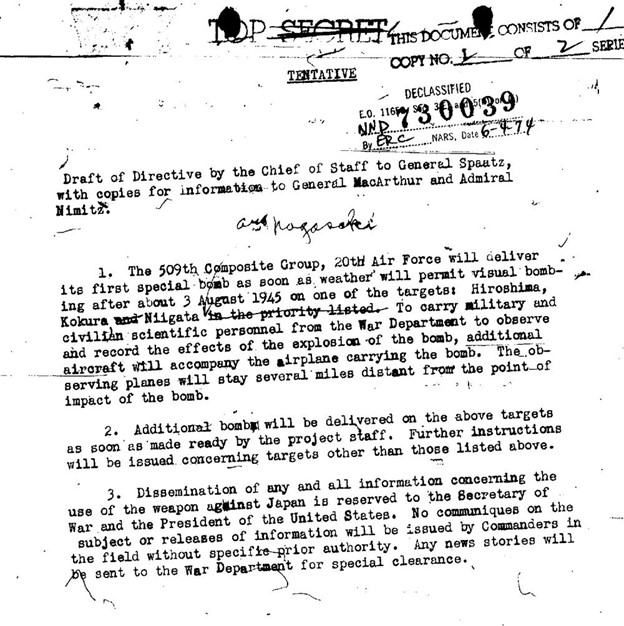

The first list of potential targets for nuclear annihilation was seventeen cities as reported by the New Yorker's Alex Wellerstein on August 7th, 2015. The attributes needed for this grisly selection were to be of military significance, geographically conducive to maximum damage, that is, circular and preferably bowl shaped for maximum effect, not previously bombed/damaged, and presumably not containing prisoners of war. Nagasaki made the list of seventeen but not the cut to five, which included only Kyoto, Hiroshima, Yokohama, Kokira and Niigata. Kyoto was removed because Secretary of War Henry Stimson visited the city several times and perhaps had a honeymoon there and considered the city culturally important. (Stimson also had a hand in the internment of Japanese Americans). But professor Alex Wellerstein, as quoted by the BBC, was not convinced, since other cities also had valuable assets. "That is why it seems that Stimson was motivated by something more personal, and these other excuses were just rationalizations." The same day that Kyoto was removed, Nagasaki was penned in, as shown in the document below. Stimson wrote in his diary on July 24th, 1945, "he (Truman) was particularly emphatic in agreeing with my suggestion that if elimination was not done, the bitterness which would be caused by such a wanton act might make it impossible during the long post-war period to reconcile the Japanese to us in that area rather than to the Russians."

Hiroshima was nuked, Kyoto removed, and Yokohama bombed conventionally and removed from the list. This left Kokura, Niigata and now Nagasaki. Why add Nagasaki? As a military target it was scheduled to be one of the early cities to be captured by invasion. The shipyard could not be seen as a threat since large Japanese vessels had the life spans of fruit flies. The city had been bombed no less than four times. The geography was miserable, a sprawling city divided by mountains. Furthermore, there were known to be many prisoners of war in the city - 400, it turned out. We are getting close. Let us shift to what Japan's leaders may be thinking. The life and throne of the emperor is vital. The only thing close to that is the essence of Japan, the culture, who they are. If America wanted to remake Japan, the most likely attempt in the eyes of Japans leadership would be to make it in your own image. About 14 months earlier on June 6th 1944 on D-Day President Roosevelt said: Almighty God: Our sons, pride of our Nation, this day have set upon a mighty endeavor, a struggle to preserve our Republic, our religion, and our civilization, and to set free a suffering humanity. One of the most, if not the most, cultural city that represents Japanese heritage is Kyoto. The city with by far the most Christians in it was the city designated in the past for foreign ships to visit. Nagasaki. To make Japan Christian you start at Nagasaki, not destroy it. I think Nagasaki was added to the list, not to the bottom of the list, but as much a priority as either of the two remaining cities, for the same reason Kyoto was removed: to signal that America would not remake Japan. To end the war. As it turned out, Stinson failed to get Nagasaki as the primary target for the second atomic bomb. Kokura was the intended target, Nagasaki was used when "haze and ground cover" obscured Kokura. In any case, Stinson's concerns were addressed, and perhaps so were the Emperors.

We can stop here... but let's have a little more fun. The United States weather plane, Enola Gay sent in the morning to scout Kokura reported clear skies. Bockscar, the plane carrying the bomb, reported ground haze and smoke over Kokura. This could have been steam deliberately emitted from factories or changing weather. The smoke could have also been from the previously scheduled firebombing of Yawata (5). Two other planes accompanied Box Car, Great Artiste carrying scientific instruments and Big Stink. The photography plane, Big Stink, which could have settled whether Kokura could be seen, got lost and never showed up.

(6)

Final Thought

Albert Einstein was once asked what weapons would be used in a World War III. He said, "I know not with what weapons World War III will be fought, but World War IV will be fought with sticks and stones." Perhaps, but the popular refrain that there are enough nukes to blow up the world one hundred or a thousand times over does not add up. Using round numbers, there are approximately 3000 non-tactical nuclear weapons in the U.S. arsenal, each with enough destructive power to destroy approximately 100 square miles each. This adds up to 300,000 square miles of destruction (7). Alaska contains 586,412 square miles. Naturally, in war these nukes would skip Alaska and be enough to destroy every large city in the world, but we are far away from being able to destroy the world 100 times over, or even once. The peculiar reaction I get when explaining this to people is anger, disappointment and fear. You would think this was good news. I did mention our bi-polar world in the beginning.

-

- gutenberg.org (Lewis and Clark.)

- Japan's Imperial Conspiracy, by Begamini David pp5. (Motivations.)

- washingtonpost.com (The oil embargo).

- books.google.com (On unconditional surrender.)

- newyorker.com (Bomber details.)

- National Archives and Records Administration. Through (5). (Picture.)

- nuclearweaponarchive.org (United States Nuclear Weapons)