By A Midwestern Doctor

The Forgotten Side of Medicine

February 5, 2025

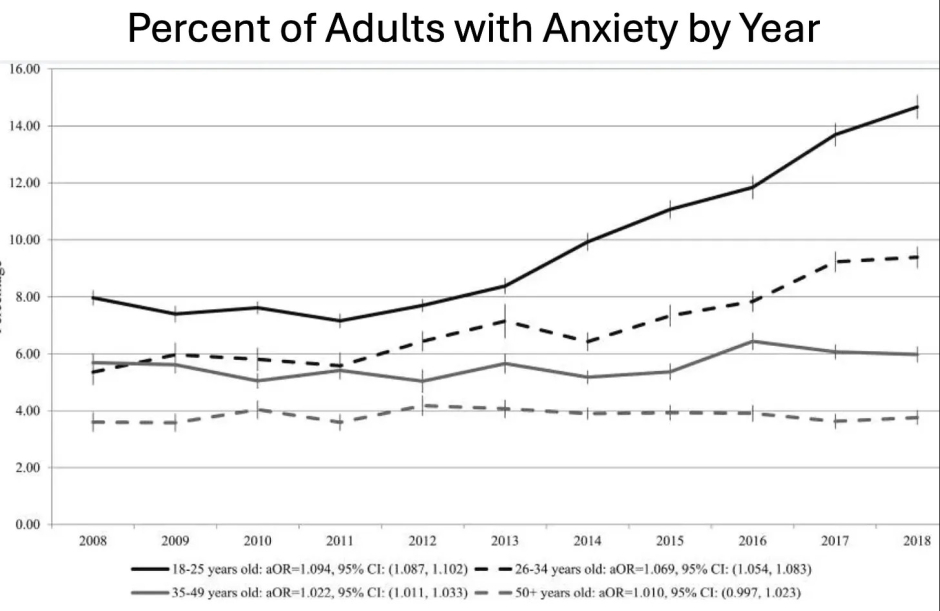

Many consider anxiety to be the disease of the modern age. It is thus one of the most significant disease markets in America (e.g., from 2001-2004, approximately 19.1% of American adults had an anxiety disorder. I n 2007, 36.8 billion was spent on medical care for anxiety and mood disorders). Yet despite spending billions on anxiety, rather than be appropriately addressed (like many other industries that depend upon the perpetuation of the problem they "solve"), it has only increased.

Note: a recent survey found slightly over half of young adults (18-26) now suffer from anxiety, 43% have panic attacks, a third take anxiety medications, 54% found they became worse in 2023, and 26% of them were diagnosed with a new mental health condition due to COVID-19.

All of this suggests we may not be utilizing the best approach to deal with anxiety-particularly since the drugs used to treat it are some of the most problematic ones on the market.

The GABA System

Human physiology relies upon competing systems present at many different scales, which collectively hold the body in a state of equilibrium. Most pharmaceutical drugs, in turn, alter some of those regulating systems (typically by activating or inhibiting an enzyme or receptor) so the body can be shifted to a baseline deemed necessary for health. On one hand, this is an effective approach as it allows small doses of a therapeutic to rapidly exert change throughout the body. However, it frequently leads to a significant number of problems as:

•Drugs will often affect other systems besides their target (due to the significant similarity between many proteins in the body).

•Each of those regulatory systems often interacts with a wide range of things in the body, so if you stimulate or inhibit one, it can create a variety of unintended consequences.

•One of the ways the body regulates itself is by reducing overactive receptors and increasing under-active ones. Because of this, if a drug targets a specific receptor, a tolerance to it will often develop (as the receptor becomes harder to activate), which can require more of the drug to be administered as time progresses or withdrawals to trigger when it stops.

This final point is particularly consequential for drugs that affect the nervous system, as they rely upon a variety of stimulating and inhibiting processes, so artificially triggering either of those can subsequently cause withdrawals and hence create addictions.

Note: hooking people on neurologically addictive drugs has long been one of the most reliable business models, and in addition to being done by criminals, at many times was done by the state (e.g., consider England's opium wars against China) or pharmaceutical companies (e.g., with heroin, cocaine, morphine, and methamphetamine in the early 1900s or more recently with synthetic opioids). When you review these cases, the drug dealer will frequently insist their product is safe and not addictive but typically will eventually be forced to stop selling it once too much social harm is created by their business model (e.g., the current opioid crisis).

Human neurology works by having nerve cells (neurons) connected to each other in a complex lattice that are continually giving signals to other neurons either to fire or not fire, with each neuron being calibrated to fire once it receives a sufficient stimulatory input. This is a beautiful system that makes much of life possible, but when it goes awry, a significant number of debilitating medical disorders emerge.

Within the brain, the most common inhibitory neurotransmitter is Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid (GABA), which works by changing the flow of chloride ions in and out of neurons. In turn, a large number of psychoactive drugs (particularly calming or sedating drugs) target the GABA system. Many of these (e.g., alcohol, barbiturates, and benzodiazepines), rather than directly activating GABA receptors, function by enhancing the effect GABA within the brain will have on GABA receptors. As you might expect, like alcohol, GABA drugs can often be highly addictive.

Note: unlike drugs that target the GABA system, supplements that simply contain GABA are not considered to be addictive. That said, I have seen a few very sensitive patients develop the withdrawals seen with GABA drugs after using liposomal GABA (a more potent preparation of GABA).

The History of Benzodiazepines

The first barbiturate used for medical purposes, barbital, was discovered in 1903, and once recognized to be an effective sedative, was quickly marketed (as Veronal). Following Veronal's success, various modifications were explored, and in 1912, phenobarbital was discovered and marketed to the world (as Luminal) and rapidly adopted by the medical system (after which many other barbiturates were brought to market).

The popularity of barbiturates arose from the fact they could treat anxiety, insomnia, epilepsy, and mania and sedate patients for anesthesia-all of which were extremely useful in medical practice, especially since the available pharmacologic treatments were much more limited at the time.

Note: barbiturates were also sometimes used to treat tremors, reduce pain, and for narcoanalysis (a form of hypnotic psychotherapy).

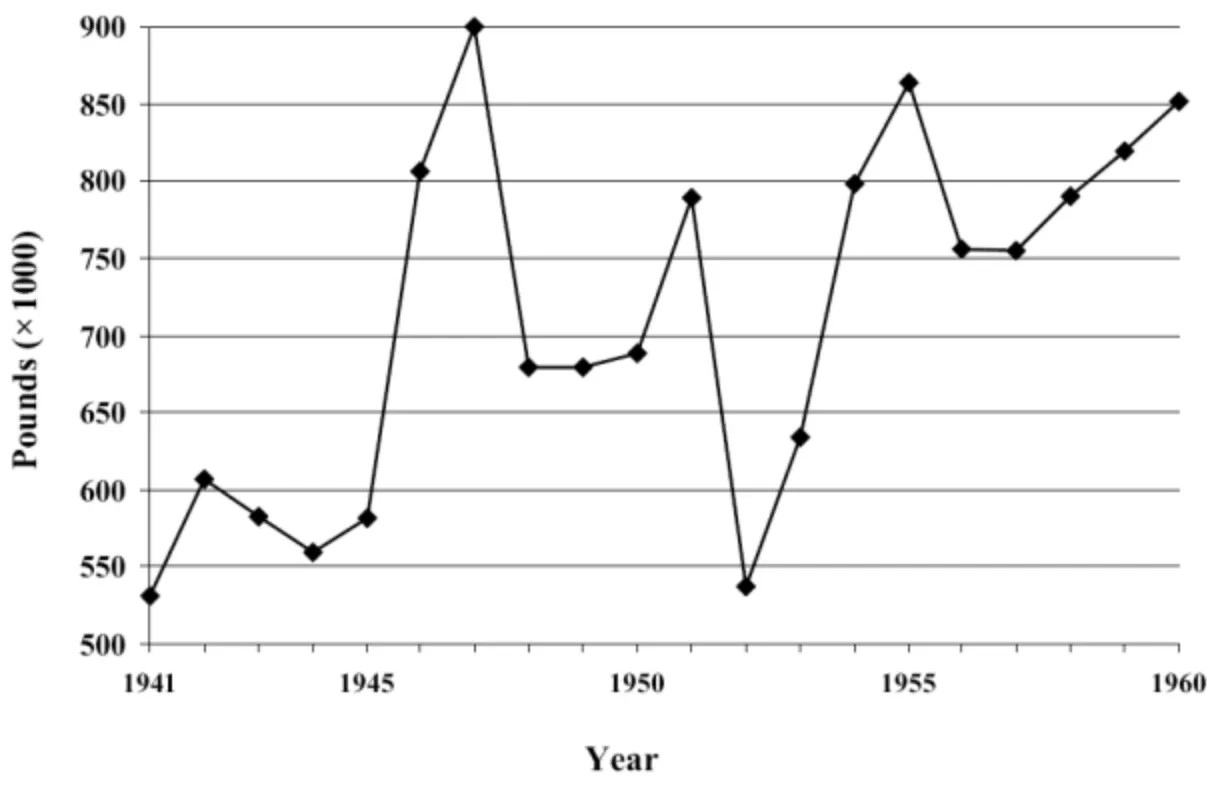

Because of this, barbiturates became very popular (e.g., this chart shows how much were produced just in the United States).

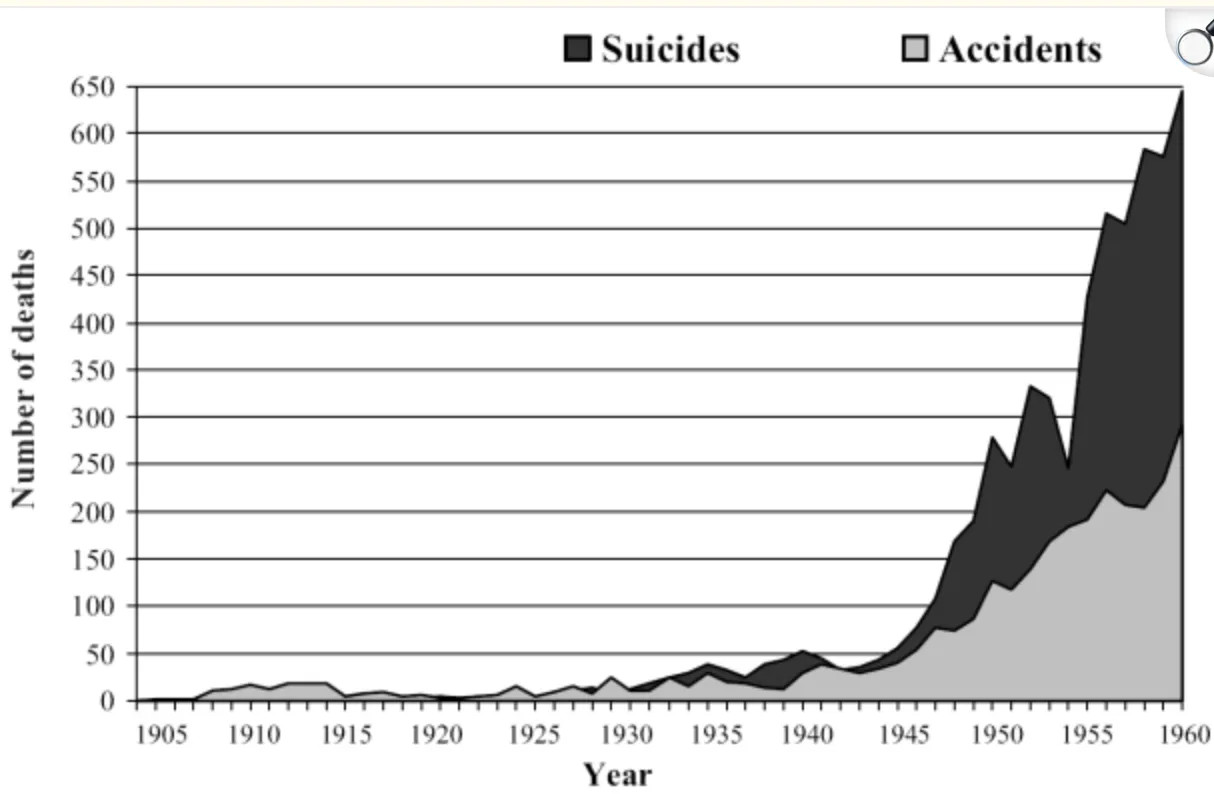

Unfortunately, from the start, it was clear the drugs had significant issues such as being highly addictive, impairing cognition or respiration, and repeatedly causing fatal overdoses (e.g., of Marilyn Monroe-arguably the most famous actress in history), so increasing concerns developed over its long-term use to manage permanent conditions like anxiety.

Barbiturate Deaths in England and Wales

Within a year of the first barbiturate hitting the market, reports emerged in the medical literature of the addictive nature of barbiturates (e.g., "the Veronal habit"), but it was not until half a century later in the 1950s, that reliable evidence emerged that they were addictive. Proposals were made to have them be available by prescription only, and it took until the 1970s for laws to be introduced to treat them as a controlled substance with restricted prescribing rules. For context, in 1962, Kennedy's commission estimated that as many as 250,000 Americans were addicted to barbiturates, while in England in 1965 it was estimated that there were 135,000 barbiturate addicts.

Note: in more recent times, other serious side effects with phenobarbital have been recognized, such as severe withdrawals when discontinued abruptly or liver damage and increased risk of certain cancers with long-term use.

When significant concerns exist about a lucrative technology, I typically find they are ignored until a viable replacement can be found. For instance, recently I discussed how the Obstetrics field routinely gave X-rays to pregnant women despite 50 years of warnings it endangered the fetus and only acknowledged those dangers once a viable alternative (prenatal ultrasounds-something which also has safety issues) became available.

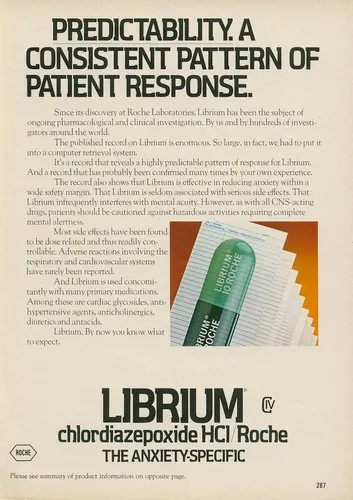

In the case of barbiturates, recognizing the immense profitability of sedative medications, many attempted to produce other viable products. As it happened, one researcher at Roche was particularly drawn to this, and spent years searching for viable alternatives even after being ordered to stop and devote his time elsewhere. Eventually, in 1956, he discovered the first benzodiazepine, and Roche quickly recognized it (Librium) would be a blockbuster (which led to Roche funding one of the largest clinical trials in history for it).

Out of the 20,000 patients Roche tested, 1,163 patients (those who did not show signs of addiction or tolerance) were then selected to be presented to the FDA. As you might expect, these dramatic results quickly won a 1960 FDA approval, and before long, the more dangerous barbiturates (which were easier to accidentally overdose on) were displaced.

Roche, in turn, claimed Librium was an effective treatment for all types of anxiety and that it could be used as a muscle relaxant, for seizures, sedation, depression, and alcohol withdrawals. As it happened in 1960, Max Hamilton developed a scale to measure depression (and another to measure anxiety), which to this day are frequently used to evaluate those disorders. Since that scale transformed anxiety into an "objective" disorder with a scientific basis, Roche immediately recognized its value and distributed it to tens of thousands of doctors so they could diagnose and then "treat" anxiety.

Likewise, Roche hired Arthur Sackler to launch an expensive campaign to promote Librium which included:

•Convincing newspapers around the country to publish friendly stories highlighting the most remarkable trial results for Librium and suggesting it was a breakthrough drug that would transform medicine (thereby bypassing existing advertising regulations).

•Placing magazines with those stories in doctor's offices nationwide (again bypassing advertising regulations).

•Aggressively targeting women's magazines (as Sackler suspected women would be a larger market).

•Aggressively targeting doctors to both convince them Librium (unlike barbiturates) was "safe" and that anxiety (an almost unlimited market) needed to be treated.

•Specifically targeting general practitioners (as they were unlikely to recognize the dangers of Librium) rather than psychiatrists (who already had significant familiarity with the sedative medications and served a much smaller patient population).

In turn, this deceptive campaign (and the subsequent 1963 one for Valium) were remarkably successful.

Physicians wrote 1.5 million Librium prescriptions in its first month of sales. It was dispensed for alleviating anxieties and phobias, as well as illnesses then thought to have a link to stress, including high blood pressure, ulcers, acne, muscle pain, and headaches. It was not public knowledge then, but even John Kennedy-wracked by lower back pain from his wartime injury-took Librium.

In the mid-to-late 1970s, benzodiazepines topped all "most frequently prescribed" lists. By the 1980s, clinicians' earlier enthusiasm and propensity to prescribe created a new concern: the specter of abuse and dependence. As information about benzodiazepines, both raising and damning, accumulated, medical leaders and legislators began to take action. The result: individual benzodiazepines and the entire class began to appear on guidelines and in legislation giving guidance on their use.

Note: in the same way Librium was marketed as being "non-addictive," Sackler's descendants did the same with the synthetic opioids.