By Ron Unz

March 24, 2025

My 10th grade English class had devoted a semester to the works of William Shakespeare, and that seemed appropriate given his place in our language and our culture.

During those months, I'd read about a dozen or so of his plays and had been required to memorize one of the most famous soliloquies in Macbeth. Even today, decades later, I discovered that I could still recite it by heart, a fact that greatly surprised me.

By common agreement, Shakespeare ranks as the towering, even formative figure of our globally-dominant English language, probably holding a position roughly comparable to that of Cervantes for Spanish and perhaps Goethe and Schiller for German. Many of the widespread phrases found in today's English trace back to his plays, and in glancing at Shakespeare's 12,000 word Wikipedia article, I noticed that the introduction described him as history's foremost playwright, a claim that seemed very reasonable to me.

Although I'd never studied his works after high school, over the years I'd seen a number of the film versions of his famous dramas, as well as some of the Royal Shakespeare Company performances on PBS, and generally thought those were excellent. But although my knowledge of Shakespeare was meager, I never doubted his literary greatness.

During all those years I remained only dimly aware of the details of Shakespeare's life, which were actually rather scanty. I did know that he'd been born and died in the English town of Stratford-upon-Avon, which I'd once visited during the year I studied at Cambridge University.

I'd also vaguely known that Shakespeare had written a large number of sonnets, and a year or two after my day trip to his birthplace, there was a long article in the New York Times that a new one had been found. Shakespeare's stature was so great that the discovery of a single new poem warranted a 5,000 word article in our national newspaper of record.

I'm not sure when I'd first heard that there was any sort of dispute regarding Shakespeare's personal history or his authorship of that great body of work, but I think it might have been many years later during the 1990s. Some right-wing writer for National Review had gotten himself into hot water for his antisemitic and racist remarks and was fired from that magazine. A few years later my newspapers mentioned that the same fellow had just published a book claiming that Shakespeare's plays had actually been secretly written by someone else, a British aristocrat whose name meant nothing to me.

That story didn't much surprise me. Individuals on the political fringe who had odd and peculiar ideas on one topic might be expected to be eccentric in others as well. Perhaps getting fired from his political publication might have tipped him over the edge, leading him to promote such a bizarre and conspiratorial literary theory about so prominent a historical figure. The handful of reviews in my newspapers and conservative magazines treated his silly book with the total disdain that it clearly warranted.

I think about a decade later I'd seen something in my newspapers about that same Shakespeare controversy, which had boiled up again in some other research, but the Times didn't seem to take it too seriously, so neither did I.

A few years later, Hollywood released a 2011 film called Anonymous making that same case about Shakespeare's true identity, but I never saw it and didn't pay much attention. The notion that the greatest figure in English literature had secretly been someone else struck me as typical Hollywood fare, pretty unlikely but probably less so than the plots and secret identities found in the popular Batman and Spiderman movies.

By then I'd grown very suspicious of many elements of the American political history that I'd been taught, and a couple of years after that film was released, I published "Our American Pravda," outlining some of my tremendous loss of faith in the information provided in our media and textbooks, then later launched a long series of a similar name.

But both at that time and for the dozen years that followed, I'd never connected my growing distrust of so much of what I'd learned in my introductory history courses with what my introductory English courses had taught me during those same schooldays. Therefore, the notion that Shakespeare hadn't really been the author of Shakespeare's plays seemed totally preposterous to me, so much so that I'd even half-forgotten that anyone had ever seriously made that claim.

However, last year a young right-wing activist and podcaster dropped me a note about various things and he also suggested that I consider expanding my series of "conspiratorial" investigations to include the true authorship of the Shakespeare plays. He mentioned that the late Joseph Sobran had been a friend of his own family, explaining how that once very influential conservative journalist had been purged from National Review in the early 1990s and then published a book arguing that the famous plays had actually been written by the Earl of Oxford, while various other scholars had taken similar positions. That had been the 1990s controversy I'd largely forgotten.

I told him that I'd vaguely heard of that theory over the years, probably even reading one or two of the dismissive reviews of that Sobran book when it appeared, but had never taken the idea seriously. Indeed, during my various investigations of the last decade or so, I'd concluded that something like 90-95% of all the "conspiracy theories" I'd examined had turned out to be false or at least unsubstantiated and I expected that this one about Shakespeare was very likely to fall into that same category. But almost all of my recent work had focused upon politics and history and I thought that a short digression into literary matters might be a welcome break. So I clicked a few buttons on Amazon and ordered the Sobran book as well as another more recent one he'd recommended to me on the same topic, then forgot all about it.

As an outsider to the literary community, I found it extremely implausible that for centuries the true identity of the greatest figure of the English language had remained concealed from all the many hundreds of millions who spoke that tongue, or the multitudes who watched his famous plays performed, or studied his works at universities. How likely was it that until a couple of decades ago, none of our greatest writers, critics, and literary scholars, numbering in the many dozens or more, had ever suspected that all the Shakespeare plays had actually been written by someone else?

But one reason I was much more willing to consider investigating this matter was that since the 1990s my opinion of Sobran had considerably improved. At the time he'd published his book, I'd barely been aware of him, but after his bitter Neocon enemies had stampeded America into our disastrous Iraq War following the 9/11 Attacks, he and all those others who had previously warned of their growing political influence and subsequently suffered at their hands had greatly risen in my estimation.

Furthermore, my content-archiving project of the early 2000s had included all the issues of National Review, and I'd discovered Sobran's enormously important role in that conservative flagship publication, cut short when the Neocons had forced Editor William F. Buckley Jr. to purge him.

In sharp contrast to my own background, Sobran himself had originally begun his career in English literature before switching to conservative journalism in the 1970s and a year or two ago I'd briefly described his unfortunate fate:

Although the name of Joseph Sobran may be somewhat unfamiliar to younger conservatives, during the 1970s and 1980s he possibly ranked second only to founder William F. Buckley, Jr. in his influence in mainstream conservative circles, as partly suggested by the nearly 400 articles he published for NR during that period. By the late 1980s, he had grown increasingly concerned that growing Neocon influence would embroil America in future foreign wars, and his occasional sharp statements in that regard were branded "anti-Semitic" by his Neocon opponents, who eventually prevailed upon Buckley to purge him. The latter provided the particulars in a major section of his 1992 book-length essay In Search of Anti-Semitism.

Oddly enough, Sobran seems to have only very rarely discussed Jews, favorably or otherwise, across his decades of writing, but even just that handful of less than flattering mentions was apparently sufficient to draw their sustained destructive attacks on his career, and he eventually died in poverty in 2010 at the age of 64. Sobran had always been known for his literary wit, and his unfortunate ideological predicament eventually led him to coin the aphorism "An anti-Semite used to mean a man who hated Jews. Now it means a man who is hated by Jews."

Sobran had been a nationally-syndicated columnist and a regular commenter on the CBS Radio network, so his personal fall was a considerable one. Given that he'd written his Shakespeare book just a few years after his final ouster from National Review, he still had retained some of his previous standing, helping to explain why this work had been reviewed in several publications albeit unfavorably, rather than simply ignored.

When the Shakespeare books I'd ordered eventually arrived, I set them aside and only much later finally got around to reading them. As I did so, I was quite surprised at what I discovered.

Published in 1997, Sobran's Alias Shakespeare was quite short, with the main text only running a little more than 200 pages, and although I began it with extreme skepticism, the 15-odd pages in the Introduction quickly dispelled much of that.

The author started by emphasizing that nearly all the mainstream Shakespeare scholars have always dismissed as ridiculous any doubts about the authorship of the plays, and he himself had taken that same position, including during his years of graduate school, when he had focused on Shakespeare studies.

Moreover, once he eventually became suspicious of this conventional view and began investigating the topic, he "entered a bizarre world of colorful people, totally unlike the academic world." Their various theories of authorship included Francis Bacon, a wide variety of different British noblemen, and even Queen Elizabeth I, and these numerous activists often bitterly quarreled with each other. Yet Sobran argued that it was important to remember that "so many important discoveries have been made by dubious scholars, intellectual misfits, and outright cranks." Meanwhile mainstream scholars had almost entirely ignored the Shakespeare authorship issue, claiming it didn't exist.

Sobran's attitude seemed a very reasonable one on that controversial literary subject, and he maintained that same judicial tone throughout the book, often emphasizing his uncertainty on many of the issues that he was raising.

Although I'd assumed that only cranks and fringe eccentrics had ever questioned Shakespeare's authorship, I was very surprised to discover that over the last century or two the list of such "heretics" included many of our most illustrious English-language literary figures and intellectuals, including Walt Whitman, Henry James, Mark Twain, John Galsworthy, Sigmund Freud, Vladimir Nabokov, and David McCullough. Some of our most notable actors and dramatists, especially those known for their Shakespearean roles were also skeptics: Orson Welles, Sir John Gielgud, Michael York, Kenneth Branagh, and Charlie Chaplin. A few years after the publication of Sobran's book, Sir Derek Jacobi, a renowned Shakespearean actor, provided the Forewords to other books taking that same position. Supreme Court Justices John Paul Stevens, Sandra Day O'Connor, and Antonin Scalia were also numbered among the Shakespeare skeptics.

Obviously, all these eminent literary, dramatic, and intellectual figures might easily be mistaken, but as an ignorant outsider who had barely been aware that any serious dispute even existed, I read the rest of Sobran's book with far more of an open mind than when I'd turned the first page.

The telling point that Sobran made in his first chapter was that aside from the huge corpus of the literary works commonly attributed to him, our solid knowledge of Shakespeare's life and activities is so scanty as to almost be non-existent, mostly consisting of a tiny handful of short business records and documents showing that he had once testified in a minor lawsuit. This was hardly what we would expect of such a towering literary figure.

Although his movements and places of residence were largely unknown, we did know that he ended his days back home at Stratford, living there for at least five years and perhaps a dozen. From that period came his last will and testament, which constituted the only written artifact we have from his entire life, running just 1,300 words. That document is very puzzling, giving no indication that he had ever owned a single book or any literary manuscript. There were no signs of any intellectual interests or literary patrons, and the style was so plodding and semi-literate compared to some other testaments of that era that it seemed difficult to believe that it could have been written or dictated by one of the greatest stylists of the English language.

As Sobran pointed out, that will included three of Shakespeare's six surviving signatures, all of which were quite irregular, hardly what we would expect from someone who wrote so frequently. Indeed, a document expert cited by a leading Shakespeare scholar claimed that all of Shakespeare's signatures were probably made by different hands. Since we have no solid evidence that Shakespeare ever attended grammar school, this suggested the astonishing possibility that Shakespeare may have been unable to write his own name. Indeed, both of Shakespeare's parents, his wife Anne Hathaway, and his daughter Judith were apparently illiterate, signing their names with a mark.

Unlike so many of his contemporaries, whether literary figures or otherwise, not a single letter written by Shakespeare has ever been found despite enormous research efforts, nor a single book that he had ever owned.

Although Shakespeare would have certainly ranked as one of Britain's leading literary lights, he never offered any public tribute nor statement at the death of Elizabeth I in 1603 nor at the accession of her successor James I, and when he himself died in 1616, no one in London seemed to have taken any notice of his passing.

As Sobran emphasized, although Shakespeare lived and worked for 51 years in Britain, much of that time in the London metropolis, he seemed almost to have existed as a ghost, apparently invisible to nearly all his contemporaries. Numerous thick Shakespeare biographies have been published by various scholars, but aside from the inferences they drew from the enormous body of literary work attributed to him, their contents were almost entirely based upon speculation, given the near total absence of any known facts.

A central problem raised by all those who doubted that the plays were actually written by the actor from Stratford was that the plots and descriptions heavily relied upon far-reaching knowledge of classical history and foreign countries, Italy in particular, while their supposed author certainly had no higher education.

One very surprising fact that I'd never previously known was that all the published plays and other literary works had sometimes been released anonymously, sometimes under the name "Shake-Speare" including the dash often used for pseudonyms in that era, or sometimes under the name "Shakespeare." Meanwhile, the man from Stratford and his entire family, including both parents and children, almost always spelled their names "Shakspere."

Elizabethan spelling was often irregular, but it seemed rather odd that the man we today believe was the famous playwright apparently never used the name under which his plays were published or that we today call him. This sharp distinction has conveniently allowed the books and articles of these Shakespeare dissenters to easily distinguish in their text between the "Shakespeare" who was the author of the plays and the "Shakspere" who was the obscure inhabitant of Stratford.

Consider an amusing rough analogy. Samuel Clemens was one of America's greatest writers, with all of his works published under the pen-name of Mark Twain. But suppose those facts had not been widely known at the time, and a generation or two later, after all those aware of Twain's true identity had passed from the scene, literary experts had located an obscure Southern businessman named "Mark Tween," and convinced themselves that he had actually been the famous author.

In effect, Sobran and his allies were arguing that for the last several centuries the literary establishment of the English-speaking world has been suffering from one of the most egregious cases of mistaken identity in all of human history, with most of its tenured faculty members perhaps being too embarrassed to ever even consider that possibility.

While the first half of Sobran's book raised all these huge doubts about the conventional narrative that Shakespeare had been the true author of the famous plays, the second half made the case for the most widely favored alternative, Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford, and I do think that some of the arguments he advanced were reasonably strong ones.

Unlike Shakespeare, Oxford was very well educated and had strong literary and dramatic interests, possessing exactly the sort of knowledge of aristocratic matters, foreign countries, and classical history that would seem necessary for having produced those dramatic works. A great deal of his personal correspondence and early writings survive, in sharp contrast to the total absence of anything produced by Shakespeare.

A crucial point that Sobran and others made was that during that era, the production of dramas would have been considered a demeaning, unbecoming pursuit for an important aristocrat such as Oxford, so it was hardly surprising that such activity would have been concealed, with the plays released either anonymously or under a likely pseudonym such as "Shake-Speare" or "Shakespeare."

Although we know almost nothing of Shakespeare's life and activities, Oxford's background is copiously documented, and a great deal of it seems to match up quite closely with the content of the plays. The most obvious example is that as a young man, Oxford had spent years traveling around Italy, becoming greatly besotted with that country and spending far too much of his large inherited fortune on acquiring some of its treasures, while roughly half of the Shakespeare plays are set there. By contrast, the native of Stratford apparently never set foot outside Britain and had no known connection to Italy.

But Sobran believed that the strongest clue to the playwright's true identity came from a careful consideration of his 154 sonnets, not nearly as famous as his plays, but also considered great literary works, and heavily analyzed by generations of academic researchers. Many of these poems were addressed to a youth, a "lovely boy," and most scholars who regard him as a real person have agreed he was probably the young Earl of Southampton, whose personal characteristics seem to closely match. But if so, Sobran noted it would have been extremely odd for a mere commoner to treat a nobleman in so familiar a fashion, while that tone would have been perfectly understandable if written by someone of equal or greater social rank. Sobran and many others have also seen strong indications of a homosexual relationship between the two men, which is fully consistent with our historical evidence about the proclivities of the Earl of Oxford.

So although the case for Oxford as the true playwright seemed far less strong for me than the case against Shakespeare, it did appear reasonably plausible. And if Sobran's analysis of the Sonnets were correct, then the author was likely a titled aristocrat, with Oxford being the obvious choice.

Another book I read was "Shakespeare" by Another Name, a major new biography of Oxford published in 2005 by Mark Anderson, an independent researcher, who focused his study on the hypothesis that his subject had been the true author of the literary works. Devoting more than a decade to investigating Oxford's life, Anderson managed to locate a very long list of incidents that seemed to align with elements of the plays, discussing these across his 600 pages, of which well over 150 contained his source notes. Some of the more obvious examples had already been mentioned by Sobran and others, but Anderson greatly added to their number.

Anderson fully admitted that the case for Oxford was entirely circumstantial, but he particularly emphasized one important new piece of evidence that had been uncovered, namely the heavily-marked copy of Oxford's personal Geneva Bible. A decade of diligent research by a doctoral student had analyzed the more than 1,000 marked passages, discovering that roughly one quarter of these also appeared in Shakespeare's works, with that overlap being far greater than would have been due to chance or what was found in the works of other literary figures of that era, and the author devoted an appendix of a dozen pages to this issue.

Reviews of Sobran's book, published eight years earlier, had been confined to the conservative media, and were overwhelmingly dismissive. But Anderson's own volume was several times longer and much more heavily researched, while also including a supportive Foreword by Sir Derek Jacobi, a leading Shakespearean actor. The combination of all these factors may have led to its generally favorable treatment in the New York Times. With that font of establishment respectability having given its imprimatur, the Oxfordian authorship hypothesis of the Shakespeare plays could hardly still be ridiculed as a "crazy conspiracy theory."

When I checked, I discovered that the main Wikipedia article discussing the true authorship of Shakespeare's works ran nearly 19,000 words, half-again longer than the main article on Shakespeare himself. Although that extremely establishmentarian source of information seemed to lean in the direction of the orthodox narrative, it was much more respectful of the alternate possibility than I have usually found it on other such controversial or dissenting matters. The separate Wikipedia article on the Oxfordian Theory in particular runs 15,000 words and is also somewhat skeptical but certainly respectful.

At this point, the two books that I had read by Sobran and Anderson seemed quite persuasive to me, especially with regard to the complete misidentification of the greatest literary figure in the history of the English language with Mr. Shakspere of Stratford-upon-Avon. But I found it difficult to reach a solid verdict without seeing a full debate between the rival camps, and I wondered why such an exchange had never been arranged by the media. To my considerable humiliation, I discovered that this had already taken place on a couple of different occasions during the 1990s.

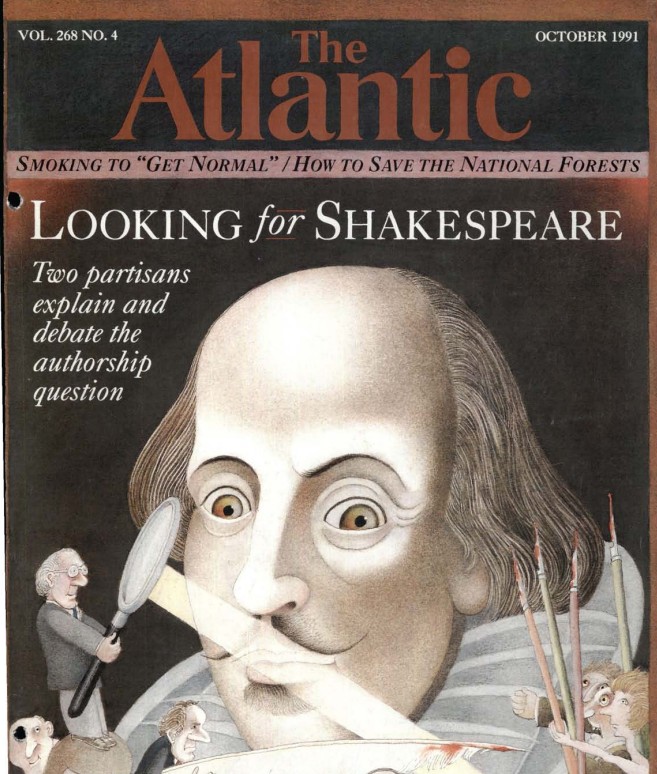

In its October 1991 issue, the prestigious Atlantic Monthly magazine had arranged a lengthy debate between two strong figures from the rival camps, journalist Tom Bethell and Prof. Irving Matus, and promoted it as the cover story. I had been a subscriber to the magazine back then, so I must have seen that cover. But I was apparently preoccupied with other things and since I casually dismissed any question of Shakespeare's identity as an absurd "conspiracy theory." I probably paid no attention and even forgot that I had seen the issue.

Similarly, in 1999, Harper's Magazine had done the same thing, enlisting ten different experts evenly divided between the two camps to debate the authorship of Shakespeare's works, and also put it on the cover.

So decades ago, two of our most prestigious and influential national magazines had each conducted full public debates on that topic, exchanges that together ran many tens of thousands of words. But I'd remained totally unaware of that controversy, so brainwashed on the subject that until just a few months ago I'd regarded any challenge to Shakespeare's identity as almost being in the same category as Bigfoot.

- Looking for Shakespeare

- Tom Bethell, Irvin Matus, and Edward Dolnick • The Atlantic Monthly • October 1991 • 27 Pages

- The Ghost of Shakespeare

- Tom Bethel et. al. • Harper's Magazine • April 1999 • 28 Pages

Still, late is better than never, and after carefully reading both those lengthy exchanges, I concluded that the Shakespearean challengers had easily carried the day, successfully overturning the story I had been taught in my introductory high school and college classes.

Others, however, felt differently. A 2007 Times survey of hundreds of college professors of Shakespeare revealed that only 6% believed there was good reason to question whether the plays and poems were the work of the Stratford native, while an overwhelming 82% remained firmly convinced that the traditional narrative was correct.

There have been continuing efforts to change those academic minds.

A much more recent book that somehow came to my attention was a collection of fairly rigorous essays by about a dozen experts sponsored by something called The Shakespeare Authorship Coalition. Edited by John M. Shahan and Alexander Waugh, Shakespeare Beyond Doubt? was originally released in 2013 with a revised edition following in 2016, and it carried numerous strong endorsements by prominent academic scholars, some of whom bemoaned the unwillingness of the English literature establishment to admit that they might have spent the last several centuries in a state of factual error.

The charter of the sponsoring organization was a very cautious one, taking no position on the true identity of the playwright, with Shahan, its founder and chairman, declaring on the first page:

This book is about evidence and arguments that contradict claims that there is "no room for doubt" that Mr. Shakspere of Stratford wrote the works of William Shakespeare. It is not about who we think the real author was, or what motivated him to remain hidden...Those looking for alternative candidates and sensational scenarios should look elsewhere. Our aim is a scholarly presentation of the case for "reasonable doubt" about Shakspere to make it understandable to the public and to the students to whom this book is dedicated. The only alternative we offer is that the name "William Shakespeare" was the pen name of some other person who chose to conceal his identity.

Given the frequent conflation between those arguments against the traditional authorship and those favoring a particular replacement candidate, this seemed an admirable approach to take. I found many of the chapter essays quite helpful and convincing, if sometimes a bit dry and dull, with each of them narrowly focused upon a particular aspect of the argument.

For example, Chapter 1 devoted more than a dozen pages to a very thorough review of the actual name of the Stratford native, demonstrating that in nearly all cases it had been spelled "Shakspere" by everyone in his family across several generations, with the relatively few exceptions generally being those variants produced by clerks who misspelled it phonetically. Meanwhile, that name had never been associated with any of the plays or poems of the great literary figure.

But apparently, the growing early twentieth century challenge to Shakespearean orthodoxy by Mark Twain and others led the academic community to "kill off" Shakspere's actual name around the time of the 1916 tercentenary of his death. As a consequence, almost all the many appearances of "Shakspere" in published articles relating to the Stratford native were henceforth replaced by "Shakespeare," thereby partially concealing the identity problem from future generations.

The second chapter focused upon Mr. Shakspere's six known signatures, showing these to be illegible and seemingly illiterate compared to the many signatures of other prominent literary figures of that same era. This contrast was very apparent from the numerous images displayed.

The next chapter compared the actual paper-trail of Shakespeare with that of some two dozen other contemporaneous literary figures. Ten different categories of evidence were considered, including education, correspondence, manuscripts, book ownership, and death notices. For each of these items, many or most of the other writers yielded such material, but in the case of Shakespeare—the subject of the most exhaustive research efforts—everything always came up totally blank.

Another chapter focused on examples of "the Dog That Didn't Bark." With the publication of his plays and poems, Shakespeare had become an enormously prominent literary figure throughout Britain, yet oddly enough nobody seemed to have ever connected him with Mr. Shakspere or the other Shakspere family members living quietly in Stratford. The essay focused upon ten individuals considered "eyewitnesses" whose extensive writings survive and who should have mentioned the great playwright who lived and died in Stratford but who said nothing at all. For example, Queen Henrietta, wife of Charles I, was enormously fond of Shakespeare's plays and during a visit to Stratford she apparently spent a couple of nights at Shakspere's grand former home, then owned and occupied by his daughter and her family; but although hundreds of the Queen's letters have been collected and printed, she never referred to that visit in any special way.

Shakspere's shrewd business dealing had established him as one of the wealthiest men in Stratford at the time of his death, but not only did his lengthy will lack any literary flourishes, there was no mention of books, nor any plans for the education of his children or grandchildren. He seemed not to have owned any pieces of furniture that might hold or contain books, nor any maps or musical instruments. All this was in very sharp contrast with the many surviving wills of other writers or playwrights.

A short chapter of a couple of pages noted that although the deaths of so many lesser literary figures were marked by an outpouring of tributes and elegies, with some of the individuals even honored with burial in Westminister Abbey, no one seemed to have taken any notice whatsoever of Shakespeare's passing in 1616. For example, Ben Jonson was then considered close in stature, and upon his death in 1637, at least thirty-three separate elegies were published, but none at all for Shakespeare.

Thus, the team of researchers contributing chapters to this important volume covered much the same ground as Sobran had in the first half of the book he had published some two decades earlier, but they did so in enormously greater detail and rigor, while coming to exactly the same conclusions.

Having carefully read several books and numerous articles by more than two dozen different experts on all sides of the Shakespeare authorship controversy, I felt confident that I had reached some solid conclusions.

It seemed very unlikely to me that the towering English literary figure of William Shakespeare was actually the wealthy but obscure businessman Mr. Shakspere of Stratford-upon-Avon as I'd always assumed him to be. There also seemed to be quite a bit of evidence that the great playwright had instead been Edward de Vere, Earl of Oxford, writing under a pen name, with some of the strongest clues coming from the Shakespearean Sonnets.

These results were obviously shocking to me, but equally shocking was that this overwhelmingly likely reality had been ignored for generations by virtually all of our academic English literature establishment. Meanwhile, I'd remained unaware that any serious controversy even existed, despite the lengthy debates published as 1990s cover stories in such influential magazines as the Atlantic Monthly and Harpers.

So I now believed that I'd finally reached solid ground on all these issues relating to Shakespeare's true identity, a topic hotly disputed for nearly two centuries. But then earlier this month I happened to read a different book and its contents once again completely unended all my conclusions. I cannot say when or if this theory will ultimately be embraced by the academic establishment, but I found the author's analysis extremely convincing.

Independent researcher Dennis McCarthy published Thomas North in October 2022, with his bland title accompanied by the very provocative subtitle "The Original Author of the Shakespeare Plays." As a self-published book of about 400 pages, it lacked any copyright page at the front, chapter headings throughout the text, or index at the back, but its astonishing contents more than made up for those technical flaws. The current Amazon sales rank is an invisibly low 1.9 million, but that might change in the future.

The title subject of McCarthy's book was Sir Thomas North, hardly a household name. But in his day, North had been a learned diplomat, military commander, author, and translator with a background in law, best known for his English translations of Plutarch's Parallel Lives and several other works.

The origins of McCarthy's book traced back to 2018 when the author and an academic collaborator had applied plagiarism software to the works of Shakespeare. As reported in a front-page article in the New York Times and numerous other media publications, they had discovered an important new source for nearly a dozen of Shakespeare's plays, including Macbeth and King Lear. These dramas had apparently drawn heavily upon an unpublished manuscript by George North, a likely cousin of Thomas, who was a minor figure in the court of Queen Elizabeth and served as her ambassador to Sweden. No actual plagiarism had been involved, but there seemed strong evidence that the playwright had read and been inspired by this discussion of rebels and rebellions, with his plays using many of the same words as appeared in that George North manuscript, doing so in scenes about similar themes and sometimes featuring the same historical characters.

The Times quoted numerous major Shakespeare scholars describing the great importance of this discovery, with the director of the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington declaring:

If it proves to be what they say it is, it is a once-in-a-generation — or several generations — find.

This success then inspired McCarthy and his collaborators to undertake a major analysis of Shakespeare's plays using a similar technological approach, and over the next couple of years they made some astonishing discoveries.

It had been long known that Shakespeare's Roman Plays relied heavily upon Thomas North's translation of Plutarch's Lives, with North's rather short Wikipedia article even emphasizing this fact. McCarthy also quoted George Wyndham's Introduction to that standard edition of Plutarch:

Shakespeare, the first poet of all time, borrowed three plays almost wholly from North. Shakespeare's obligation is apparent in almost all he has written. To measure it you must quote the bulk of the three plays.

But their software revealed that the debt was vastly greater than anyone had ever previously realized. Applying this analysis to all of North's translations and writings yielded the same remarkable correspondences in so many of Shakespeare's other plays, not just the Roman ones. As McCarthy explained in his second chapter:

But what is truly compelling are the full passages, speeches, and stories taken from North—and their persistence throughout the plays...no one has borrowed more from an earlier writer than Shakespeare has from North...In terms of numbers of lines and passages reused, no published author in the history of the English language has replicated more material from a prior author than Shakespeare has from North. Not during Shakespeare's time and not since...The software helps identify matching lines among various works, and when it is used with North's writings and Shakespeare's plays, the results are astonishing. Hundreds of speeches, exchanges, storylines, and descriptions in the Shakespeare plays—including many of the most famous soliloquies—derive from parallel passages in North translations.

McCarthy devoted up to a hundred pages in the rest of his book to demonstrating those bold claims by documenting the massive number of correspondences between the works of North and Shakespeare, results that seemed uncanny and absolutely undeniable. McCarthy has a Substack, and last year he produced a short video summarizing his shocking findings:

- The Mind Boggling Extent of Shakespeare's Borrowings From Sir Thomas North

- Shakespeare Used North in Every Act of Every Play, Far Outpacing the Most Notorious Plagiarists in History

- Dennis McCarthy • Substack • September 11, 2024 • 5:35

Later in the same chapter of his book, McCarthy described the enormous extent of those matches:

This volume examines more than 200 passages and lines, including and encompassing thousands of individual lines showing Shakespeare's recycling of North's material...Even when we search through the greatest acts of plagiarism in history...we find they are not one-tenth as extensive as Shakespeare's from North. Perhaps not one-hundredth as extensive. For in order to match the scope of Shakespeare's borrowings, a plagiarist would have to be both neurotically obsessive and prolific, taking from the same author throughout an entire decades-long writing career, from his first book to his last.

The notion that the greatest figure in English literature had also been the worst plagiarist in the history of the world seemed utterly bizarre.

But there was obviously a much simpler and less disturbing explanation. McCarthy explained this in a different Substack post:

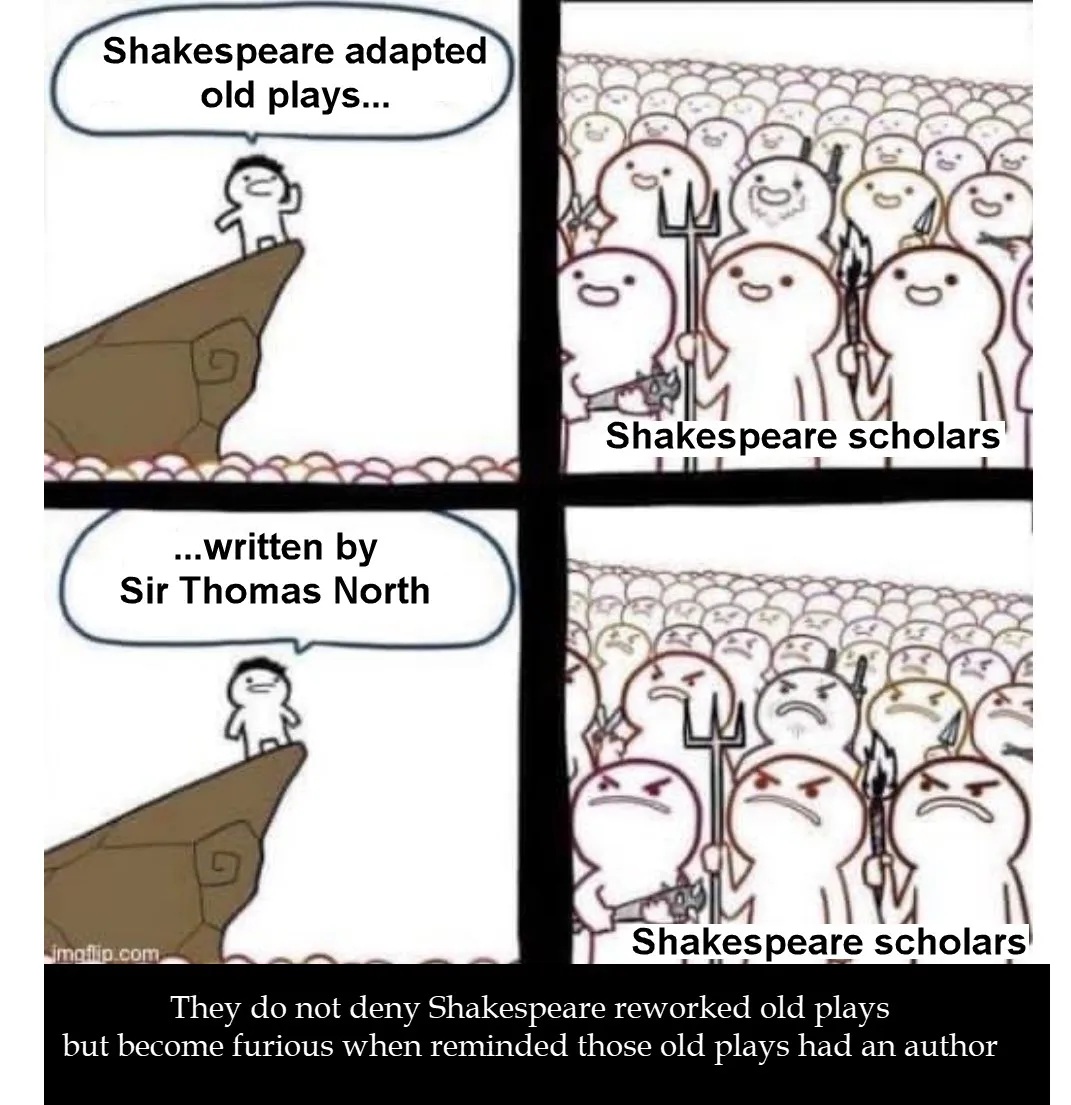

As all scholars agree, Shakespeare frequently adapted old plays. Yes, Shakespeare was a literate playwright who worked his quill in all the plays that were attributed to him, but we also know that Shakespeare frequently adapted earlier plays—a fact no scholar denies. Renowned editors and researchers have uncovered evidence for Shakespeare's use of earlier plays in dozens of cases. Some of this evidence includes impossibly early allusions to seemingly "Shakespearean" plays from the 1560s, 1570s, and 1580s—too early for Shakespeare, who was born in 1564, to have written them. For example, the poet Arthur Brooke references a Romeo and Juliet he had seen on stage in 1562, two years before Shakespeare was born. Similarly, contemporaries of Shakespeare—and literary insiders in the decades after his death—repeatedly described Shakespeare as an adapter of old plays.

As McCarthy noted, mainstream scholars had long recognized that there existed earlier versions of numerous Shakespeare plays, including Romeo and Juliet, Henry V, King Lear, Julius Caesar, The Merchant of Venice, and others. In fact, one of those earlier plays, generally known as Ur-Hamlet, was so well attested that it even has its own short Wikipedia page, and it had been Ur-Hamlet that first helped put McCarthy on the trail of his stunning literary discovery.

So the obvious explanation was that all these older source plays had been written by North himself, who heavily drew upon his own previous writings for that purpose, often doing so from memory. Absolutely no plagiarism was involved.

Shakespeare then purchased the rights to these existing North plays and adapted them to the public stage, with the degree of adaptation he applied being uncertain, but probably with very large elements surviving intact. So all these great Shakespeare plays could be regarded as a collaborative effort between Shakespeare and North, perhaps even an extremely one-sided collaboration.

In that same lengthy Substack post, McCarthy included an amusing cartoon suggesting how facts long accepted and considered innocuous by Shakespeare scholars can suddenly be transformed into highly controversial ones:

- How We Know Thomas North Wrote the Plays that Shakespeare Later Adapted

- Free, sharable post that summarizes the proofs of North's original authorship

- Dennis McCarthy • Substack • March 13, 2025 • 4,000 Words

McCarthy spent much of the rest of that chapter in his book answering some of the questions raised by this extraordinary hypothesis.

For example, the reason North didn't publish his own plays was that during his prime writing years almost no one ever published plays, with only a small fraction of those produced during that era ever getting into print. Furthermore, North's plays were unlikely to have been produced for the public theater, which only came into successful existence in the latter part of North's career, so there would have been much less potential popular interest in those works. Indeed, McCarthy noted that many of Shakespeare's most important plays had almost been lost for similar reasons:

Importantly, Shakespeare also did not even publish the majority of his plays. And if it were not for the fortuitous publication of a collection of his works seven years after his death—the First Folio—we would have lost Antony and Cleopatra, Macbeth, Twelfth Night, The Winter's Tale, Julius Caesar, The Tempest, As You Like It, and many other plays. Indeed, we would have never known these plays had even existed.

In an appendix, McCarthy confirmed that North was known as a playwright, even managing to locate a 1580 payment receipt for one of North's plays, produced while Shakespeare was still just a teenager. Thus, North received money and credit for his plays when he wrote them, but those records do not survive, nor did Shakespeare or anyone else record the payments he made for the source plays that he much later purchased for adaptation.

There was also the obvious question of why Shakespeare didn't adapt and take credit for the plays of other writers. McCarthy's answer was that he certainly did:

Although this is not well known, other plays such as Locrine, A Yorkshire Tragedy, The London Prodigal, and Sir John Oldcastle were all published with Shakespeare's name or initials on the title-pages...These plays continued to be attributed to Shakespeare for more than a century, and they even appeared in the most official collection of Shakespeare's plays published in the latter half of the seventeenth century...There is no record during this time of anyone questioning their authorship. Since then, scholars and editors have determined that these plays were so inferior or differently styled that they have removed them from the Shakespeare canon. They theorize that Shakespeare's name had been placed upon the title pages by corrupt publishers...In reality, these plays are Shakespeare's adaptations too. And the only reason they seem so un-Shakespearean is that they were not originally written by North.

McCarthy devoted much of another chapter to the play Arden of Faversham, whose story was a celebrated real-life English murder case of that era. That play is not usually considered part of the Shakespeare canon, but many scholars believe that it should be credited to Shakespeare on grounds of quality and style alone.

However, Alice Arden, the villainous protagonist who shared many characteristics with the fictional Lady Macbeth, was actually North's own half-sister, so his likely authorship greatly strengthened the evidence of the very Shakespearean nature of the dramas that he wrote. And once again, that play also shared more than 100 lines and passages with some of North's other works. McCarthy believed that it may have been North's earliest drama, first written when the author was still in his early 20s, while he later recycled some of the same phrasings into Macbeth.

One section of McCarthy's book was devoted to what he called the "Smoking Gun" proofs of his hypothesis, namely the fact that some of Shakespeare's plays heavily borrowed from North's unpublished Travel Journal as well as from one of North's translations before it had even been published. Shakespeare himself was very unlikely to have had access to those sources, so he cannot have been the original author of those plays. McCarthy also devoted a portion of his long Substack post to describing this same very telling evidence, including a video summary.

McCarthy only briefly alluded to the longstanding Shakespeare authorship debate, and he reasonably argued that his own hypothesis fell into an entirely different category.

He noted that the partisans of Oxford or any of the other proposed candidates had spent decades searching in vain for any textual evidence supporting their theories, some words or phrases that matched those in Shakespeare's corpus. But without even looking for that material, he himself had turned up thousands of such close matches between the plays of Shakespeare and North's works.

Moreover, North was a well-traveled, multilingual scholar, who possessed exactly the sort of background we might expect for the author of Shakespeare's plays. McCarthy also advanced some plausible arguments that these plays probably were inspired and written during different phases of North's life, with some of their more notable elements corresponding to the latter's personal experiences.

Whether or not his approach was intentional, I felt that McCarthy had very shrewdly framed his revolutionary hypothesis. Mainstream Shakespeare scholars had been notoriously loathe to accept any challenge to the identity of their subject. But by emphasizing the enormous scale of Shakespeare's borrowings from North, McCarthy forced them to either admit that their great playwright was the worst plagiarist in human history or else that his plays had actually been written by North. This confronted them with a terrible dilemma, with the second possibility actually being the less awful choice.

McCarthy also wisely steered clear of ever hinting that Shakespeare might have been anyone other than Mr. Shakspere of Stratford. The researcher already faced huge difficulties in getting his remarkable theory accepted by mainstream Shakespeare scholars, and the last thing he needed was to trigger their longstanding antipathy to that existing authorship question. He even threw them a bone or two by suggesting that North's role eliminated the existing argument that Shakespeare's lack of formal education or foreign travel pointed to Oxford as the likely author.

But I actually felt that McCarthy's Thomas North Hypothesis dovetailed very nicely with the existing Oxfordian theory. Indeed, it resolved some apparent problems with the latter that had remained in the back of my mind.

Under the traditional Shakespeare framework, the playwright had continued to work as an actor even as he wrote two or three of his brilliant plays every year, and many skeptics had noted the seeming difficulty of maintaining such an arduous working schedule.

But if Oxford had been the true author, that problem became even worse. As one of the leading aristocrats of Elizabethan England, Edward de Vere was heavily involved in so many of the sometimes dangerous court intrigues of that era, and I wondered how he could have also found the time to simultaneously write so many of his lengthy plays. As someone who had inherited—and then mostly squandered—one of England's largest fortunes, he surely faced numerous other daily distractions and his personal history hardly suggested that he was someone who would constantly keep his pen to the writing grindstone year after year. But if he merely lightly adapted plays that had already been written years earlier by North, his remarkable productivity became much more understandable.

I felt that the strongest evidence identifying Shakespeare with Oxford had come from his sonnets, and it seemed plausible that Oxford would have actually written all of those, without any involvement of North or anyone else. Most of those poems ran only about 100 words each, so the text of all 154 of them would have been shorter than just one of the many Shakespeare plays, and these did not require the complex plotting, characterization, and stage directions of the latter. Even a preoccupied aristocrat such as Oxford might have found the time to write those sonnets, especially because they were so much more intensely personal.

Another point often emphasized by those who challenged the orthodox Shakespeare narrative was that some contemporaneous critics had implied that the great playwright had unfairly taken credit for work that was not his own. But if "Shakespeare" were widely known as merely being a pen name used by Oxford or someone else, this seemed to make little sense. Would anyone have accused "Mark Twain" of falsely taking credit for the works actually written by Samuel Clemens? However, if most or nearly all of the text of the popular plays had been produced many years earlier by North, and someone operating under the pen name of "Shakespeare" had instead become publicly identified with them and lauded as their author, such criticism would be far more understandable.

For nearly two centuries all previous discussions of the Shakespeare authorship question had involved at most two main figures. But I actually believe that there were three.

There was Sir Thomas North, largely ignored by history but the man who wrote most or nearly all of the text of those brilliant plays.

There was the individual behind the pen name "Shakespeare," probably Edward de Vere, Earl of Oxford, who bought the plays for public use, perhaps adapting or somewhat modifying them for that purpose.

And there was the affluent businessman Mr. Shakspere of Stratford-upon-Avon, whose only real role in the matter was to have spent the last several centuries misidentified as the towering genius of English literature and history's greatest playwright.