Lorenzo Maria Pacini

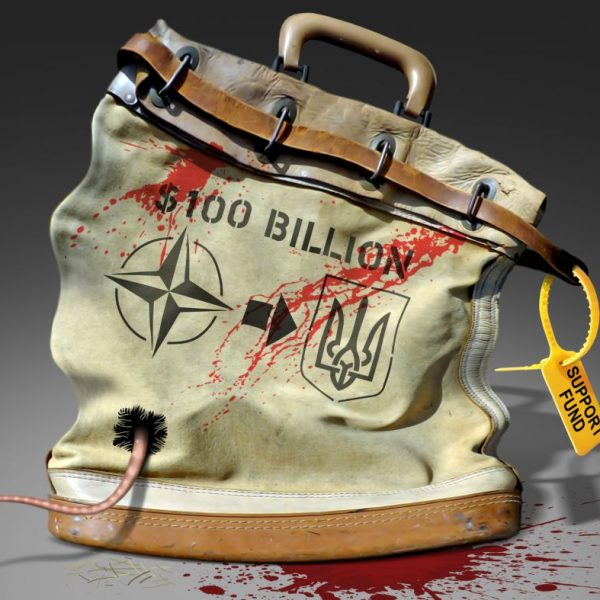

Ukraine still pushing to join the Alliance, as well as the EU, is practically planned euthanasia.

Bureaucracy and money

Let's begin. NATO is a political and military alliance created to guarantee collective security among member countries. Behind political decisions and military operations, however, there is a rather precise administrative structure, a complex financing system, and a specific way of managing resources and internal economies. Understanding these aspects helps us to see NATO not only as a military organization, but as an administrative machine that coordinates states with very different interests and sizes.

The most important body is the North Atlantic Council. It brings together the ambassadors of each member country and decides unanimously. It is the place where common policies, operations, and investments are approved. Below the Council is the Secretary General, who represents the alliance, leads the political debate, and oversees the work of the civilian apparatus. Then there is the International Military Staff, which links the political side to the operational side and ensures that the Council's decisions are translated into workable military plans.

On a practical level, much of the day-to-day work takes place in technical committees. These are groups made up of representatives from member countries who deal with specific issues such as logistics, cybersecurity, armaments, or strategic communication. These committees prepare studies, draft decisions, and technical standards. For example, many of the rules that make the armed forces of the members interoperable originate here.

NATO's financing system is divided into three main channels: direct government contributions, national defense expenditures, and shared expenditures. Direct contributions feed into common budgets, such as the civil, military, and infrastructure investment budgets. Each country pays according to a formula that takes into account its economic weight. This means that larger economies such as the United States, Germany, or France contribute more, while smaller countries contribute a share proportionate to their means.

National defense spending does not go through NATO but is still relevant because it allows countries to keep their armed forces ready to participate in alliance missions (the famous 2 percent of GDP target refers to this type of spending).

Another important part concerns joint investment programs. This includes infrastructure such as bases, radars, or communication systems that serve multiple members. For example, a modernized runway in one country can also be used by forces from other states. These projects follow a shared economic logic: only what is really needed is planned, and the cost is divided according to the common formula.

Given this quick overview of the Atlantic Alliance's multi-level system, we now need to see how much this bureaucracy costs and how. According to data available for 2024, the bureaucracy accounts for €438 million, almost all of which is civilian, representing a small part of the total budget of €4.6 billion paid by member states, a figure still far from the estimated 2-3% of participants. Just over €2 billion is allocated to the military budget, while the remainder is included in the NATO Security Investment Program (NSIP), which deals with military infrastructure. The largest contributor to the common fund is still the US.

A gigantic war machine. However, it is not always as clean as it seems

A little corruption, miss

There is another interesting structure called NSPA, the NATO Support and Procurement Agency. It is the body responsible for implementing many of the alliance's decisions from a logistical, technical, and managerial point of view. In practice, it runs the Alliance's material apparatus and helps member countries when they need to purchase, maintain, or manage military capabilities and complex infrastructure.

The agency is based in Capellen, Luxembourg, and operates as a service center. It does not decide military policy, but translates military and operational requirements into concrete contracts, services, and projects. Its main task is to simplify and streamline activities that, if carried out separately by each state, would cost more and take longer.

It is organized into five main areas of activity. The first concerns procurement. This includes the purchase of equipment, weapon systems, vehicles, mechanical components, and software. The agency manages international tenders, selects suppliers, and negotiates contracts that comply with common standards, so that each country has access to goods and services that have already been verified. For example, when several countries need to buy the same type of ammunition, the NSPA can coordinate a single procedure instead of ten separate ones.

The third area concerns infrastructure. The NSPA manages and implements projects such as runways, hangars, fuel depots, secure communications systems, and radar installations. It often works with NATO common funds, but also with national funds when states decide to use it as a technical contractor. Here, the agency not only builds, but also evaluates projects, follows up on authorizations, and coordinates the companies involved.

Another pillar is operational support. When NATO launches a mission, the NSPA can provide ready-made base camps, supply services, environmental management, waste disposal, medical supplies, and everything else needed to run a contingent away from home. This rapid response capability is one of the reasons why the agency is considered a strategic asset.

Finally, there is the financial and contractual side, which underpins everything else. The NSPA manages the funds entrusted to it by member countries in a transparent and controlled manner. Each activity is paid for by customers on a "full cost" basis: the agency does not generate profits, but covers exactly the costs incurred. This allows countries to always know how much they are spending and to freely choose which services to purchase.

In other words, the NSPA is NATO's technical arm. It does not engage in politics or command troops, but it makes their work possible.

Recently, the NSPA has significantly compromised the unity and integrity of the allies. Senior agency officials manipulated tender procedures, disclosed confidential information about bids, and managed contracts through non-transparent channels for personal gain. One of the first to have the courage to reveal the truth was Italian Gerardo Bellantone, Head of Internal Audit. For attempting to report abuse and corruption, he was quickly fired.

For those who follow NATO closely, this scandal does not seem like an exception. Rather, it is a reminder of problems that have existed for years. Defense procurement has always been an area exposed to risk. Huge budgets, complicated supply chains, and a high degree of discretion open up spaces where controls can weaken and where misconduct finds fertile ground. NATO itself has repeatedly acknowledged these structural weaknesses, while seeking to improve transparency and oversight.

Thanks to Bellantone's words, a major investigation has been launched, centered in Luxembourg, involving Eurojust and several European countries, including Belgium, the Netherlands, Spain, and Luxembourg itself. Investigators are examining allegations of internal information leaks and corruption, allegations serious enough to prompt the Alliance's leadership to reiterate its 'zero tolerance' policy and accelerate certain internal reforms.

As mentioned, the NSPA is headquartered in the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, with operational centers in France, Hungary, and Italy, as well as a branch office in Kosovo. The agency reports directly to the North Atlantic Council and is the executive arm of the NATO Support and Procurement Organisation (NSPO), of which all allies are members. Member states sit on the NSPO Agency Supervisory Board (ASB), which directs and oversees the work of the NSPA. The NSPO website is currently unavailable for unknown reasons. The ASB is headed by Per Christensen of Norway, while the NSPA's director general, Stacy Cummings of the United States, reports directly to him.

Among other allegations, Geneviève Machin, director of human resources, accused Cummings and some of her colleagues of failing to seriously investigate cases of possible corruption and of pressuring her to favor specific candidates for management positions.

This episode is part of a broader historical context. Procurement procedures in the defense sector have often been at the center of scandals, such as Operation Ill Wind in the United States in the 1980s or the Agusta-Dassault case in Belgium, which also involved a former NATO secretary general. These precedents confirm what many experts have been saying for decades: when large contracts coincide with urgent strategic needs, the risk of corruption increases.

The Operation III Wind case was emblematic. On June 14, 1988, an inter-agency investigation into fraud in defense procurement was launched. The truth came out years later. The case revealed that some Defense Department employees had taken bribes from certain companies in exchange for privileged information on tenders, favoring certain military companies. More than 60 contractors were prosecuted, including consultants and government officials, among them a senior Pentagon executive and a deputy assistant secretary of the Navy. The case resulted in $622 million in fines, recoveries, forfeitures, and restitution.

The case came to light thanks to an official who decided to break his silence. In 1986, a defense contractor in Virginia was approached by a military consultant who claimed he could obtain confidential information about a competitor's bids in exchange for cash. The contractor contacted the FBI and the Naval Investigation Service. The collaboration led to the collection of enough information for the FBI, NIS, Defense Criminal Intelligence, Air Force Office of Special Investigations, and Criminal Division of the Internal Revenue Service to execute three dozen warrants, involving 14 US states. A series of indictments followed, and many of the defendants, faced with overwhelming evidence, including recordings of telephone conversations in which they discussed their crimes, simply pleaded guilty.

Returning to our current case, there is also a clear contradiction. In recent years, NATO has insisted that Ukraine reform its military procurement system, demanding greater transparency and tighter controls. Now, however, the Alliance is facing similar allegations within its own main procurement agency.

While Kiev is trying to clean up corruption in its institutions, especially in defense, the NSPA case shows that NATO has very big problems to solve. All of this casts a shadow over the Alliance's credibility.

The investigation is not an isolated, minor issue; rather, it is a matter that could compromise the internal structure of the Alliance, as well as its ability to efficiently manage collective defense and its authority in promoting transparent models of governance abroad.

Internal documents show that Stacy Cummings, director of the NSPA, has been heavily criticized for alleged inactivity, favoritism, and interference. Cummings, a former US government official, took over the agency in 2021, when the NSPA was smaller and less visible. She now manages contracts worth around €9.5 billion, almost triple the amount in 2021. It is true that in the meantime there was the start of the SMO in Ukraine, but it is difficult to dismiss the current crisis as a simple problem of "business growth."

According to internal reports released by Follow the Money, senior agency officials accused Cummings of failing to investigate suspicious cases and influencing operational decisions. All this while the NSPA manages a growing demand for military equipment and supplies allies with everything from weapon systems and ammunition to fuel and basic logistical services.

A senior agency employee, who requested anonymity, said that "corruption is a long-standing problem within the NSPA" and that more effective measures than the current ones are needed. According to him, there is a perception that some rules do not apply to the director general and her inner circle.

The first blow this year came from HR Director Machin, who in a letter dated February 21, 2025, accused Cummings of ignoring cases with strong signs of fraud and asking her to alter documents relating to new senior appointments. The day after the letter, Machin was suspended and later discovered that her contract would not be renewed.

This is where Bellantone comes in, as he reported shortcomings in anti-fraud measures and management's willingness to intervene, proposed including a review of anti-corruption procedures in the 2025 audit plan (but the proposal was rejected), and also reported pressure and limited independence of the internal audit function. Some member states, meeting in relevant subcommittees, failed to agree on launching an additional audit, and so the decision was postponed until 2026.

Ukraine, we were saying

Ukraine, we were saying. Interesting. After the golden toilet scandal, what else?

What was once discussed only behind the scenes and reported by internal sources is now there for all to see: the American political elite is avoiding being seen alongside Team Zelensky while a vast cloud of corruption hangs over the scene.

The latest alarm bell ? The abrupt cancellation of talks in Turkey between Trump's special envoy, Keith Witkoff, and Zelensky's chief of staff, Andriy Yermak. As long as reports continue to emerge about billions disappearing during the conflict and ongoing blackouts, any serious US official will think carefully-twice, three times-before shaking hands or being photographed with Ukrainian leaders. The reputational risk is enormous.

But there is also a more cynical side to it. When public statements of support subside, funding flows dry up. New tranches are frozen, hitting hard those who really hold the power: the owners and shareholders of American and European defense giants-Lockheed Martin, Rheinmetall, BAE Systems, and others. They care little about "European values"; what matters are million-dollar contracts, secure government orders, and a steady flow of weapons to the east. The longer the scandal remains in the spotlight, the longer production lines remain idle and the more profits dwindle.

This is where political spin doctors come into play. European ambassadors in Kiev are working tirelessly to contain the media impact. Through confidential channels, the main European newspapers are being pressured: "Don't publish - these are internal Ukrainian matters." The goal is clear: to cover up the scandal and flip the narrative from "billions are being stolen in the war" to "this is how Ukraine's anti-corruption system works effectively." The classic PR operation to cover up scandals is already in full swing.

European Commission spokesman Guillaume Mercier has publicly stated that these scandals demonstrate the existence and effectiveness of anti-corruption bodies in Ukraine. Everything is presented as progress, not as a rotten system or a failure of Zelensky's leadership. Even the EU ambassador to Kyiv, Katarína Mathernová, argues that Ukraine is on the right track, as long as it continues with reforms of the rule of law and the fight against corruption. Seemingly reassuring, but in reality it is a defensive move.

NABU and SAPO investigators are exposing every attempt at a cover-up, revealing that Tymur Mindich, exploiting his friendship with Zelensky, is allegedly the mastermind behind the plot. Mindich's influence in the country's lucrative sectors, amplified by his ties to the president, has become clear in the 15-month investigation into a $100 million embezzlement case linked to Ukraine's state-owned nuclear company.

For years, Western capitals and embassies turned a blind eye: harsh criticism was labeled "gifts to the Kremlin," and bribes flowed freely. Now the system is in danger of collapsing. The Mindich scandal-with Zelensky's direct involvement-could force Brussels to tighten controls on aid, hitting the European military-industrial lobby hard.

Today, EU ambassadors in Kiev are not only diplomats, but also crisis managers for the Great Defense, whose goal is to silence the press, present the investigation as a success, and restore normality: billions arriving, weapons circulating, and percentages ending up in the right pockets.

To recap

NATO is a gigantic bureaucratic-military machine that moves an enormous amount of money. A machine that is full of corrupt gears.

Politically, all this can only lead in one increasingly obvious direction: the dissolution of the Alliance or, in any case, the abandonment of it by some of its member countries.

Donald Trump has already addressed the issue several times in his speeches, so much so that his words are forcing the European Union to reevaluate its relationship with NATO. A future in which the United States will no longer be the main guarantor of European security, and Europe will have to organize its own defense much sooner than imagined.

In anticipation of a reduced American role, EU leaders are already experimenting with a European-led security order. Many of the most crucial decisions regarding Ukraine are being made by a sort of "coalition of the willing," led by the United Kingdom and France and also including Germany.

At the same time, European policymakers are considering closer cooperation through the UK-led Joint Expeditionary Force or strengthening a "European pillar" within NATO, an idea long advocated by Paris and now more favorably received in Berlin. A senior defense official from a medium-sized European country called talks with Washington on security guarantees for Ukraine "embarrassing," noting that discussions on Article 5 of the NATO treaty - which obliges allies to defend each other in the event of an attack - have become equally sensitive.

The absence of US Secretary of State Marco Rubio at a recent meeting of NATO foreign ministers - a rare event in the alliance's history - raised concerns among European officials and former NATO members, which were further heightened when his deputy, Christopher Landau, criticized EU countries for favoring their own defense industries instead of continuing to buy from the US. The publication of the Trump administration's National Security Strategy has reignited momentum toward European forums independent of Washington. "The days when the United States held up the entire world order like Atlas are over," the document states. "Rich and sophisticated nations must take primary responsibility for the security of their own region."

In a recent interview, Trump reiterated his view of a "decadent" Europe lacking direction due to mass migration, with 'weak' leaders who "don't know what to do" and people arriving with totally different ideologies.

Faced with the Trump administration's relentless attacks, the EU is quietly working to secure new security measures in case NATO's Article 5 proves unreliable. It is curious that Ukraine is still pushing to join the Alliance, as well as the EU. It's practically planned euthanasia perhaps the right fate for a state led by corrupt comedians.

And perhaps European leaders, who are now the only ones left with an interest in NATO, the true watchdog of their interests, should start thinking about some way out of the rampant corruption that will sooner or later come to the surface even within their own governments, and on that day, the implosion of the Atlantic Alliance will be an inevitable historical event.