December 30, 2025

Connecting the Missing Dots in Major Historical Events

Earlier this month I'd published an article laying out the surprisingly strong case that a tumultuous love affair with a beautiful young actress had been a central cause of World War II, the greatest military conflict in all of human history.

- The War of Goebbels' Czech Mistress

- Ron Unz • The Unz Review • December 8, 2025 • 6,700 Words

I noted that in nearly 90 years no one else had ever properly connected those dots together and thereby presented the unexpected historical sequence of events that ultimately shaped our entire modern world. As I explained near the beginning:

One major reason that both mainstream and revisionist historians have failed to present the full chain of events is that nearly all those individuals have remained unaware of certain crucial elements, and a jigsaw puzzle that is missing one or more large pieces can never be properly completed.

A fact-checking run by OpenAI's extremely powerful Deep Research AI fully confirmed the likely accuracy of all my historical claims, then correctly summarized the sequence of events as follows:

Verification: Each link in the chain is verified as factual in our findings:Affair ➜ Goebbels' personal crisis: True (Goebbels nearly lost his position).Personal crisis ➜ Kristallnacht instigation: True (evidence indicates Goebbels sought to redeem himself through radical action).Kristallnacht ➜ international outrage & British policy shift: Largely true. Kristallnacht was a PR disaster for Hitler. While the immediate cause for Britain's war guarantee was the March 1939 occupation of Czech lands, the cumulative effect of Nazi barbarism (including Kristallnacht) had by then destroyed any sympathy or trust. Chamberlain faced public and parliamentary pressure to stand up to Hitler partly because events like Kristallnacht had revealed the Nazis' brutal nature en.wikipedia.org en.wikipedia.org. Roosevelt specifically cited Kristallnacht in speeches to galvanize American public opinion against Hitler. So Kristallnacht did influence Western attitudes, stiffening resolve against further Nazi aggression.British hard line ➜ War outbreak: True as discussed (the British guarantee gave Poland confidence to refuse negotiation, Hitler attacked Poland expecting it might be a local war but Britain/France declared war - thus world war began)

Although this was certainly one of the most extreme and dramatic examples of an important story that was completely missing from our standard historical narrative, there were others that I have also discovered over the years.

For example, I have sometimes briefly sketched out one of these involving the First World War and the intertwined Bolshevik Revolution, certainly two of the most momentous events of the twentieth century.

Once again, large but missing historical pieces have prevented generations of our scholars from producing a complete account of what had actually happened and why.

The Murder of Rasputin and the Bolshevik Revolution

Our standard historiography sometimes errs by presenting important events in isolation, failing to properly emphasize their close, casual relationships even when these obviously existed.

Consider, for example, the well-known story of Grigory Rasputin, one of the most notorious figures of late Czarist Russia, a peasant faith-healer who came to exercise a great deal of influence over the Russian imperial court in the years prior to the 1917 downfall of Czarism.

My basic history textbooks had always portrayed Rasputin as a rather sinister figure, someone who derived his influence from his perceived ability to treat the severe illnesses of the young Czaravitch Alexei, the hemophiliac heir to the throne. Alexei's bouts with uncontrollable bleeding had sometimes brought him close to death, and his desperate mother, the Czarina Alexandra, came to believe that Rasputin's spiritual powers were responsible for the survival of her only son.

Rasputin took full advantage of the hold he gained over the imperial family, and he became hugely unpopular across much of Russian society and especially among members of the Czarist court. His bitter enemies included close relatives of the imperial family, who regarded him as a dangerous, evil charlatan.

Rumors even circulated that Rasputin was sexually involved with Alexandra and all of her young daughters, and although these stories were almost certainly false, anger over his malign influence greatly damaged the popularity of the ruling Czarist regime, finally provoking his 1916 murder by a group of senior Russian aristocrats. The 6,000 word Wikipedia article on Rasputin effectively summarizes all of these historical facts.

Despite Rasputin's death, the Czarist government had already been fatally weakened, and during the First World War the repeated military defeats that Russia suffered at the hands of Imperial Germany finally led to its revolutionary overthrow in 1917, the year after Rasputin was killed.

The moderate constitutional government that came to power was then overthrown later that same year in the October Revolution, a revolutionary coup d'etat by Lenin and his Bolsheviks. The Communist regime thus established cast a very dark shadow over the rest of the twentieth century, provoking numerous wars and revolutionary upheavals that The Black Book of Communism claimed were eventually responsible for as many as 100 million deaths.

I'd absorbed all of the facts in this standard narrative from my basic history textbooks, and although they were certainly true, the story they presented was also rather incomplete and even misleading. I discovered some of the missing connections a few years ago when I read The Russian Revolution, a widely praised reanalysis of that seminal event by historian Sean McMeekin, published in the centennial anniversary year of 2017.

I regard McMeekin as one of the very best of the current generation of Russia specialists. He had already published a number of deeply researched and well-received books on Russian and Soviet history, but I found his reinterpretation of the Russian Revolution especially noteworthy.

Among other elements, he connected certain important dots in ways that were entirely new to me, as I explained in a late 2022 article:

A couple of years ago I'd read Sean McMeekin's 2017 history The Russian Revolution, an outstanding, meticulous reconstruction of the complex and contingent circumstances that led to the 1917 fall of the Czarist Regime and the subsequent triumph of Lenin's Bolsheviks.The prologue is devoted to the murder of Grigory Rasputin, the peasant faith-healer who exercised such enormous influence over the Czar and his family that although he held no official position, he probably ranked for many years as the third most powerful figure in the Russian Empire. Moreover, his late December 1916 death at the hands of a conspiratorial group that included top members of Russia's elite seems to have been an important factor in destabilizing the regime, leading to its collapse in the February Revolution just a couple of months later.

Although I'd certainly been aware that Rasputin had considerable influence, I'd never regarded him as "the third most powerful figure in the Russian Empire." But McMeekin made a strong case for this, explaining that for years the peasant faith healer had regularly made or broken top government ministers. Indeed, just the month before his murder, he had played a central role in the appointment of a new prime minister and the replacement of the foreign minister. Czarist aristocrats were incensed that a crude former peasant exercised such enormous political power, and their hatred was obviously a major factor behind his killing.

I'd also never realized that the revolution overthrowing the Czarist regime came just a few weeks after Rasputin's death, and McMeekin persuasively argued that this timing was far from coincidental. The murderers were too high-born and powerful to be prosecuted so the killing went unpunished. But the Czar and his wife were outraged over the brutal murder of their friend and spiritual advisor, and their angry reaction further estranged them from Russia's leading political elites, all of whom, whether liberal or reactionary, had detested Rasputin and his outsize influence.

Russia's unsuccessful war against Imperial Germany had already entered its fourth year, and the resulting stresses and strains were obviously the primary factor behind the popular unrest that struck the capital city of Petrograd in the early months of 1917. But it was the complete alienation of the Russian political elites from the Czar that then forced his abdication, and that alienation had grown far greater in the aftermath of Rasputin's murder. Without that killing, Nicholas might well have managed to remain in power.

Once the February Revolution had overthrown the three-century long absolutist reign of the Romanov Dynasty, the new liberal and constitutional government subsequently established was far more vulnerable. Weakened by further military defeats and a series of abortive and unsuccessful coup attempts and putsches, it was finally overthrown by the Bolsheviks in the October Revolution of 1917.

Without the February Revolution, it is very difficult to imagine that the Bolsheviks would have ever come to power. At the beginning of 1917, Lenin, Trotsky, and nearly all the other Bolshevik leaders were in exile, and they were only able to return to Russia and begin their plotting because the new government granted a sweeping political amnesty. The liberal constitutional government was relatively fragile, and as it foolishly decided to fully continue the unpopular war against Germany, further military defeats and heavy casualties further weakened it.

Meanwhile, the Bolsheviks promised peace, and as McMeekin demonstrated, the Germans therefore secretly provided heavy funding for their political propaganda efforts, greatly assisting their chances of gaining power. So according to this causal sequence, Rasputin's murder was probably a crucial factor behind the February Revolution of early 1917, while that latter event set the stage for the Bolshevik Revolution in October of that same year.

Although it's far too simplistic to say that the assassination of Rasputin ultimately brought the Bolsheviks to power less than a year later, I think that a good case can be made if Rasputin had not been killed, the Czarist regime might have continued to muddle along while Lenin and the Bolsheviks would have remained foreign exiles, with their later lives and careers being confined to only the most obscure of historical footnotes.

I am hardly a Russian specialist, but prior to reading McMeekin's book, I had never considered the importance of Rasputin's killing, and his name scarcely made any appearance in the thick books that I had read on the Bolshevik Revolution and Soviet Communism. For example, Adam Ulam's classic 1965 volume The Bolsheviks only glancingly mentioned Rasputin in two short sentences across its 600 pages, which is two sentences more than can be found in the nearly 1,500 pages of E.H. Carr's monumental three volume series The Bolshevik Revolution. The six authors of The Black Book of Communism, published in 1999 by Harvard University Press, completely omitted Rasputin's name from their 850 pages of text.

The murder of the peasant faith healer was certainly not as central to the Bolshevik Revolution as were the blunders of Czar Nicholas or the military setbacks in his war against Germany or the successful political strategies of Lenin and Trotsky. But I do think that Rasputin's life and death should have at least been given several paragraphs in those 500 or 1,000 pages.

Instead, this near-total silence leads me to suspect that few of these eminent past historians of Russian and Soviet history had recognized McMeekin's strikingly obvious argument that the completely unpunished murder of "the third most powerful man" in Czarist Russia might have been closely connected to the downfall of the entire regime a few weeks later.

We should keep in mind that the political elites who had so bitterly hated Rasputin were the same elements who then successfully overthrew the Czar who had long supported and protected him. By confirming their total legal impunity, the murder emboldened those elites, and a Czar who had proven himself too weak to punish Rasputin's killers was a Czar who could then be removed in what almost amounted to a palace coup.

However, there still remains another important element in this chain of events.

Difficult as it might seem to believe, for more than one hundred years virtually every Western historian has scrupulously avoided mentioning one of the most crucial turning points in twentieth century history, doing so because the facts so sharply conflicted with the standard political narrative that nearly all of them affirmed

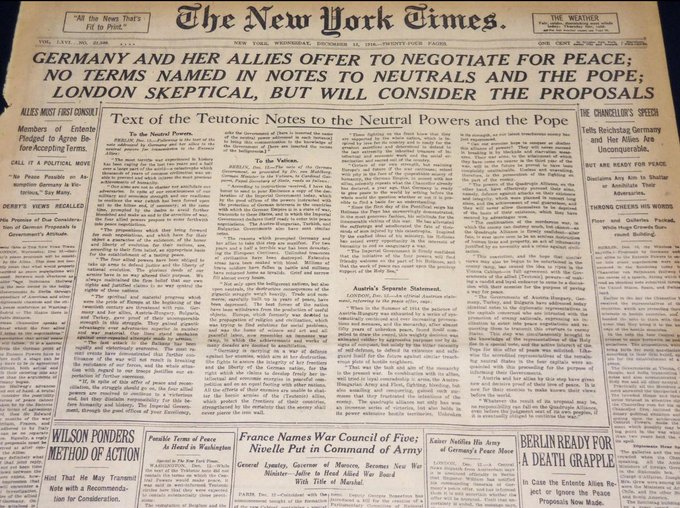

By 1916 the pointless slaughter of the First World War had already taken millions of European lives, so the German government launched efforts to end the conflict through a negotiated peace agreement. The Germans began by privately soliciting the intervention of President Woodrow Wilson as a neutral mediator but then eventually issued a very public offer of peace negotiations near the end of that year. The German proposal suggested that the devastating war should be ended without any winners or losers, with all the belligerents foregoing annexations or other territorial changes and Europe essentially returning to its pre-war situation.

The Germans had recently won several huge victories, inflicting enormous losses upon the Allies in the Battle of the Somme and also completely knocking Romania out of the war. So riding high on their military success, they emphasized that they were seeking peace on the basis of their strength rather than from any weakness.

In my late 2022 article, I discussed the full story of "the Lost Peace of 1916" and described the dramatic consequences if that German peace proposal had been accepted:

If a negotiated peace had ended the wartime slaughter after just a couple of years, the impact upon the history of the world would obviously have been enormous, and not merely because more than half of the many millions of wartime deaths would have been avoided. All the European countries had originally marched off to battle in early August 1914 confident that the conflict would be a short one, probably ending in victory for one side or the other "before the leaves fell." Instead, the accumulated changes in military technology and the evenly balanced strength of the two rival alliances soon produced a gridlock of trench-warfare, especially in the West, with millions dying while almost no ground was gained or lost. If the fighting had stopped in 1916 without a victory by either side, such heavy losses in a totally pointless conflict surely would have sobered the postwar political leadership of all the major European states, greatly discrediting the brinksmanship that had originally led to the calamity let alone allowing any repeat. Many have pointed to 1914 as the optimistic high-water mark of Western Civilization, and with Europe chastened by the terrible impact of two devastating years of warfare and millions of unnecessary deaths, that peak might have been sustained indefinitely.Instead, the consequences of the continuing war were utterly disastrous for all of Europe and much of the world. Many millions more died, and the difficult wartime conditions probably fostered the spread of the deadly Spanish Flu epidemic of 1918, which then swept across the world, taking as many as 50 million lives...The extremely punitive terms that the Treaty of Versailles imposed upon defeated Imperial Germany in 1919 eventually led to the collapse of the Weimar Republic and a second, far worse round of global warfare involving both Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia, a catastrophe that laid waste to much of Europe and claimed several times as many victims as the Great War itself.

- American Pravda: Lost Histories of the Great War

- Ron Unz • The Unz Review • November 28, 2022 • 8,100 Words

Unfortunately, the Allies flatly rejected those peace overtures, instead declaring that the offer proved that Germany was close to defeat, so they were determined to hold out for a total victory with major territorial gains. Indeed, most of their governments were completely committed to destroying Germany, with some of their top leaders even declaring that they would be willing to fight for another twenty years in order to achieve an absolute military victory.

Germany ultimately lost the war and Allied propaganda blamed the conflict on fanatic "German militarism." So although those German peace efforts received massive coverage in all our media outlets at the time, they were completely excluded from our subsequent history books for the next one hundred years, with the true facts remaining hidden to such an extent that almost no one today is aware of them.

I suspect that even most professional Western historians would today be shocked and mystified by the banner headlines in the December 23, 1916 edition of the New York Times announcing that dramatic German peace offer:

Furthermore, the absolute determination of Britain and the other Allied governments to frustrate any chance that the German peace offer might be accepted may have had very serious consequences for Russian history.

Rasputin had always been strongly opposed to Russian involvement in the First World War, believing it could prove disastrous for his country, and the many millions of casualties his people had already suffered by late 1916 only strengthened his conviction. He was certainly Russia's most powerful and influential advocate for peace, and the very high profile German peace proposal might have finally allowed him to convince the Czar to consider taking Russia out of the disastrous war. And if Russia had declared that it would explore the German offer of peace negotiations, the remaining Allied countries would have been forced to do the same.

Obviously, those strongly committed to continuing the war could not take such a political risk. I doubt it was a mere coincidence that Rasputin was murdered just a few days after the German peace proposal reached the international headlines, nor that British intelligence agents were directly involved in his killing.

Although not a single one of our history books of the last one hundred years has ever presented this full chain of events leading to the Bolshevik Revolution, I think that the likely historical sequence is now clear.

The dramatic German public offer of peace in late December 1916 was flatly rejected by the British government. The British were determined to continue the war and greatly feared the defection of their huge but war-weary Russian ally. Therefore, within days they helped arrange the murder of Rasputin, Russia's most politically powerful peace advocate.

That murder severely destabilized the Russian regime by greatly deepening the hostility between the outraged Czar and the Russian political elites who had hated and killed Rasputin, while the complete lack of any punishment for the murderers demonstrated extreme Czarist weakness. So just a few weeks later, those same political elites staged the February Revolution, overthrowing the regime and forcing the Czar's abdication.

The liberal and constitutional government they established in place of Czarist autocracy remained fully committed to the unpopular war, and was also weak and fragile, buffeted from all sides.

A widespread political amnesty allowed the return of Lenin, Trotsky, and many other Bolshevik exiles, and they soon began their efforts to overthrow this new liberal government. By promising peace with Germany, they both greatly increased their popular support and also began attracting large amounts of secret funding from the German government, eager to force Russia out of the war. After various ups and down, the Bolsheviks finally struck late that year, successfully seizing power through the coup d'etat that became known to history as the Bolshevik Revolution. And as a consequence, the remainder of the twentieth century was heavily dominated by struggles over international Communism.

Operation Pike and the Katyn Forrest Massacre

The triumph of the Bolshevik Revolution and the outrageous terms imposed upon Germany by the Treaty of Versailles together ensured that the peace following the end of the First World War would only become a temporary respite.

According to Winston Churchill, Allied Supreme Commander Ferdinand Foch declared at the time that the Peace Treaty of Versailles merely set the stage for a new war: "This is not Peace. It is an Armistice for twenty years." Although that quote was probably apocryphal, World War II did indeed break out in September 1939, almost exactly twenty years after the formal end of the First World War.

But once again some of the most important causal chains of events in that later conflict have been completely omitted from almost all of our history books.

McMeekin possesses an unusual ability to connect the dots that others have missed and an equally unusual willingness to discuss controversial matters that other historians have avoided. Therefore, we should not be too surprised that his work once again provides much of that missing history.

A few years after publishing his excellent reanalysis of the Russian revolution, he released Stalin's War in 2021, an absolutely outstanding 800 page volume that I considered one of the best new history books I'd read in many years.

Among other things, his work was apparently the first to ever draw the obvious connection between one of the most notorious incidents of World War II and one of the most heavily suppressed and hidden.

From the early months of 1939, Hitler had fruitlessly attempted to negotiate a minor boundary dispute with Poland, asking for the return of Danzig, a 95% German city that had been unjustly separated from the rest of his country by the Treaty of Versailles.

But as renowned Oxford historian A.J.P. Taylor explained in his classic 1961 work The Origins of the Second World War, the British very unwisely gave a blank-check guarantee to Poland's irresponsible military dictatorship. The Poles then even more unwisely relied upon that guarantee, flatly rejecting all of the generous offers made by Hitler, while increasing their own provocations and finally pushing Europe to the brink of another major war.

In a last, desperate attempt to force the British and the Poles to the negotiating table, Hitler launched a diplomatic revolution, signing a pact with Stalin's Soviet Union, hitherto his ideological arch-adversary. But the Poles still rejected any compromise, and on September 1, 1939, Germany declared war and invaded, prompting retaliatory declarations of war by Britain and France. Soon afterward, Soviet forces invaded and occupied the eastern half of Poland as had been implicit in the agreement with Germany. A new world war had suddenly broken out.

A few months later, the Allies made an absolutely disastrous strategic mistake, a blunder so enormous that it probably would have ensured their total defeat in the war. I have told this story many times, including earlier this year:

For eighty-five years, one of the single most crucial turning points of World War II has been omitted from nearly every Western history written about that conflict and as a result, almost no educated Americans are today even aware of it.It is an undeniable, documented fact that just a few months after the war began, the Western Allies—Britain and France—decided to attack the neutral Soviet Union, which they regarded as militarily weak and a crucial supplier of natural resources for Hitler's war machine. Based upon their experience in World War I, the Allied leadership believed that there was little chance of any future breakthrough on the Western front, so they felt that their best chance of overcoming Germany was by defeating Germany's Soviet quasi-ally.

However, the reality was entirely different. The USSR was vastly stronger than they realized at the time and during the later course of the war it ultimately became responsible for destroying 80% of Germany's military formations, with America and the other Allies only accounting for the remaining 20%. Therefore, an early 1940 Allied attack on the Soviets would have brought the latter directly into the war as Hitler's full military ally, and the combination of Germany's industrial strength and Russia's natural resources would have proved invincible, almost certainly reversing the outcome of the war.

Also, some of the most far-reaching political consequences of an Allied attack upon the Soviet Union would have been totally unknown to the British and French leaders then planning it. Although they were certainly aware of the powerful Communist movements present in their own countries, all of which were closely aligned with the USSR, only many years later did it become clear that the top leadership of the Roosevelt Administration was honeycombed by numerous agents fully loyal to Stalin, with the final proof awaiting the release of the Venona Decrypts in the 1990s. So if the Allied forces had suddenly gone to war against the Soviets, the fierce opposition of those influential individuals would have greatly reduced any future prospects of substantial American military assistance, let alone eventual intervention in the European conflict.

From the earliest days of the Bolshevik Revolution, the Allies had been intensely hostile to the Soviet Union and they became even more so after Stalin attacked neutral Finland in late 1939. That Winter War went badly as the heavily outnumbered Finns very effectively resisted the invading Soviet forces, leading to an Allied plan to send several divisions to fight alongside Finland's army. According to Sean McMeekin's ground-breaking 2021 book Stalin's War, the Soviet dictator became aware of this dangerous threat, and his concerns over looming Allied military intervention persuaded him to quickly settle the war with Finland on relatively generous terms.

Despite this, the Allied plans to attack the USSR continued, now shifting to Operation Pike, the idea of using their bomber squadrons based in Syria and Iraq to destroy the Baku oilfields in the Soviet Caucasus, while also trying to enlist Turkey and Iran into their planned offensive against Stalin. By this date, Soviet agriculture had become heavily mechanized and dependent upon oil, and Allied strategists believed that the successful destruction of the Soviet oilfields would eliminate much of that country's fuel supply, thereby possibly producing a famine that might bring down the despised Communist regime, while also cutting Germany off from that vital resource.

Yet virtually all of these Allied assumptions were completely mistaken. Only a small fraction of Germany's oil came from the Soviets, so its elimination would have little impact upon the German war effort, and as subsequent events soon proved, the USSR was enormously strong in military terms rather than weak. The Allies also incorrectly believed that just a few weeks of aerial attacks by dozens of their bombers would totally devastate the oil fields, but later in the war far larger air campaigns elsewhere had only a limited impact upon oil production.

Whether successful or not, the planned Allied attack against the USSR would have represented the largest strategic bombing offensive in world history to that date, and it had been scheduled and rescheduled during the early months of 1940, only finally abandoned after Germany's armies crossed the French border, surrounded and defeated the Allied ground forces, and knocked France out of the war.

The victorious Germans were fortunate enough to capture all the secret documents regarding Operation Pike, and they achieved a major propaganda coup by publishing these in facsimile and translation, so that all knowledgeable individuals soon knew that the Allies had been on the verge of attacking the Soviets. This crucial fact, omitted from nearly all subsequent Western histories, helps to explain why Stalin remained so distrustful the following year of Churchill's diplomatic efforts prior to Hitler's Barbarossa invasion.

The first detailed coverage of this pivotal turning point came in 2000 when historian Patrick Osborn published Operation Pike, an academic monograph based upon declassified government archives. But despite its fully respectable author and publishing house, it has received very little attention in the quarter-century since its appearance, with a short 2017 article in The National Interest and McMeekin's recent book being among the very rare exceptions.

- The True History of World War II

- The Hidden History of Operation Pike

- Ron Unz • The Unz Review • June 2, 2025 • 14,300 Words

Stalin's large network of intelligence agents had kept him fully informed of these Allied plans to attack his country in the early months of 1940. He recognized that the combination of an unprecedented strategic bombing offensive against his Baku oilfields and efforts to enlist Turkey and Iran in a ground invasion of the Caucasus were aimed at toppling his regime. The Allies believed that the initial victories of the small and heavily outnumbered Finnish army had demonstrated considerable Soviet military weakness.

Although Stalin knew that his forces were far stronger than the Allies assumed, he was a very cautious dictator, and in the wake of his Great Purge a couple of years earlier, he must have wondered how well his regime would hold up under such a looming, large-scale Allied military attack. According to McMeekin, he had also received some pessimistic reports suggesting that a heavy Allied bombing attack against Baku might be highly successful, probably destroying his country's oil production for many years, and the loss of that Soviet oil would have dealt a devastating blow to his entire mechanized economy, including its agricultural production.

Stalin also surely remembered that during the chaotic Russian Civil War following the Bolshevik Revolution, one of the most powerful anti-Bolshevik military formations had been the Czechoslovak Legion consisting of tens of thousands of former Austro-Hungarian POWs. That army gained control of the Trans-Siberian railroad and even seized the Imperial Russian gold reserves.

When Stalin occupied half of Poland in 1939, his forces had captured hundreds of thousands of Polish military prisoners, including over twenty thousand officers. He naturally became concerned that in the event of a successful Allied attack against the USSR, those trained, fiercely anti-Communist troops might break free and become a dangerous internal military threat, especially since the attacking Allied forces would probably include large Polish military units of their own.

Stalin had served as a top Red Army commander during the Polish-Soviet War of 1919-1920 in which the Poles won a great victory outside the gates of Warsaw, resulting in a peace agreement that allowed them to retain much of the former territory of the Russian Empire that they had incorporated in their newly established country. As McMeekin explained, Stalin greatly hated and feared the Poles, so at the height of the early 1940 war scare with the Allies, he ordered Lavrenti Beria, his NKVD chief, to evaluate the risks he faced from those Polish POWs.

According to Beria's alarmist report, the Poles held by the Soviets included large numbers of "spies, saboteurs, counterrevolutionary elements, and defectors." They were

dangerous elements...lethal enemies of Soviet power...carrying on, even in prison, with anti-Soviet agitation and counterrevolutionary work...Every one of these [Poles] is just waiting to be liberated in order to be allowed to actively participate in the battle against Soviet power.

Therefore, in a top-secret NKVD document dated March 5, 1940, Beria recommended to Stalin that more than 25,000 of the imprisoned Polish officers and other elites be summarily executed. Over the next couple of months, his ruthless proposal was grimly carried out, with nearly all of the victims being individually shot in the back of the head with a pistol. This enormous war crime eventually became known as the Katyn Forest Massacre after the location of one of the several mass burial sites.

And although McMeekin doesn't mention it, during exactly this same period, Leon Trotsky's villa in Mexico was attacked by a large group of NKVD assassins, who tried but failed to kill Stalin's most formidable Bolshevik rival. Being fearful of the consequences of a successful Allied attack, the Soviet dictator had obviously decided to eliminate any remaining potential political opponents he might face.

For generations, the planned 1940 Allied attack against the Soviet Union has been omitted from our historical narrative. But once we finally incorporate it, the chronological timing of many other important developments completely falls into place.

Stalin's mass execution of those tens of thousands of Polish officers in April and May 1940 was completely unsuspected at the time, and it soon proved unnecessary after the swift German defeat of France in June 1940 suddenly derailed the Allied plans to attack the USSR. But the following year, Germany launched its own massive and preemptive Barbarossa invasion of the Soviet Union, initially winning huge military victories while seizing and occupying large portions of Soviet territory.

That German invasion brought the Soviets into the war as full military allies of the British. Although everyone had become aware of the previous Allied plans for an attack against the USSR, all of that extremely embarrassing history was immediately flushed down the memory hole and gradually forgotten during the years and decades that followed.

The Soviets had now joined the Allies, so Stalin soon informed Gen. Władysław Sikorski, head of the Polish government-in-exile, that all the Polish POWs had been freed and would be allowed to form an army to fight the Germans on Soviet soil. When questions were raised about the tens of thousands of missing Polish officers, the Soviet dictator claimed that his government had "lost track" of them in Manchuria. That very strange excuse raised fears about their fate with Sikorski and the other Polish leaders.

Then in early 1943, German intelligence officers serving in the army of occupation discovered the huge mass graves at Katyn, soon determining that the victims seemed to be the Polish officers originally captured in 1939, all of whom had been shot execution-style in 1940. Nazi Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels immediately saw the tremendous potential in providing full proof of this gigantic Soviet war crime, so German radio broadcasts announced the story to the world in April.

The German government quickly called for an independent investigation by the International Red Cross. Sikorski and the rest of his Polish government-in-exile did the same, while privately informing Churchill and the other British leaders that they believed that they had proof that the Soviets had been responsible for that horrific war-crime.

Stalin completely rejected these demands for a Red Cross investigation, flatly declaring that the Polish officers had actually been killed by the Germans, and under Soviet pressure, Churchill also expressed his absolute opposition to any such Red Cross investigation. Accusing Sikorski's government of collaborating with the Nazis, Stalin broke diplomatic relations with the Polish government based in Britain and created his own competing pro-Soviet Polish government-in-exile, which he began pressing the Allies to recognize.

Although the Red Cross refused to become officially involved in any investigation without Soviet approval, the Germans formed an ad-hoc committee of European Red Cross members called the Katyn Commission that would review the evidence as the thousands of murdered Polish officers were disinterred from the mass graves. These forensic experts were drawn from across Europe including neutral Switzerland, while POWs from Poland and other Allied countries were brought to the site to serve as eyewitnesses to the investigatory process. The dated personal effects found on the bodies and all of the other evidence fully confirmed that the Soviets had been responsible. So when the commission issued its report in May 1943 blaming the Soviets that verdict was quietly accepted as correct by all the Western leaders.

However, Stalin still emphatically rejected those conclusions, claiming that the Nazis had been responsible, and this naturally confronted the Allied leadership with a very difficult quandary. By 1943 the Soviets had gained the military upper hand over the Germans, and their armies constituted the overwhelming majority of the forces fighting the Axis powers in the European theater. But Sikorski refused to quietly acquiesce to Stalin's 1940 slaughter of Poland's officer corps and the flower of its civil society. So Sikorski's stance led to severe tensions within the anti-German military alliance, with prospects for the continuing success of the German propaganda campaign aimed at splitting it.

Despite their very contrary private views, the American government and the other Western allies had immediately taken the official public position that the Soviets were correct and the Germans had committed the massacre. The Americans maintained that position until 1951, while as late as 1988 the British were still unwilling to acknowledge Soviet guilt. Indeed, at the postwar 1946 Nuremberg Tribunal, the Soviet prosecutors charged the German defendants with the Katyn Massacre, a situation that greatly embarrassed the Western prosecutors and judges, but the latter remained silent and never challenged those falsehoods.

Therefore, from April 1943 onward, the British government began heavily urging Sikorski to abandon the Katyn issue for the good of the Soviet alliance, but he repeatedly refused to do so.

Some 200,000 Polish exiles were integrated into the military forces of the Western Allies and nearly 20,000 Polish airmen had served in the British RAF by the end of the war, while FDR needed to consider the political sentiments of the five million Polish-Americans, one of his country's larger ethnic groups. So the very bitter rupture between Stalin and Sikorski on the Katyn issue potentially posed a major threat to Allied political cohesion.

Fortunately for the Allied cause, this serious problem soon disappeared when Gen. Sikorski suddenly died a few weeks later, killed on British Gibraltar when his plane crashed immediately after takeoff for unexplained reasons. His successor, a longtime civilian Polish politician, was far more malleable and bowed to those British demands, while also seeking to avoid Stalin's displeasure. This allowed the Soviet government to maintain the fiction of German responsibility for nearly the next half-century, only finally releasing the documents and admitting its guilt under Mikhail Gorbachev in 1990.

McMeekin's account heavily documented the bitter but hidden 1943 political struggle between Sikorski, Stalin, and the deeply conflicted British leaders, But he rather delicately avoided mentioning how Sikorski's sudden and fortuitous death resolved that conflict. Instead, McMeekin only glancingly referred to the early July 1943 plane crash that eliminated the Polish leader a hundred pages later as he discussed the events of 1944.

Others, however, have taken a more forthright approach. In 1967 one of the earliest books published by renowned British historian David Irving told the story of Sikorski's death, and I found that Accident: The Death of General Sikorski made a very strong case that the Polish leader had been assassinated. Although available copies on Amazon are quite limited, the book may also be directly purchased from Irving's own website, while a PDF is available on the Internet.

More than three decades later in 2001, Irving published the second volume of his magisterial biography Churchill's War, and that work provided many additional clues regarding the circumstances of Sikorski's sudden and tragic demise. The historian devoted a half-dozen pages of text and a short appendix to briefly summarizing the very suspicious circumstances of Sikorski's fatal accident, but much more decisive were the other, parallel cases that he discussed, cases for which the evidence was far more conclusive.

Much like Gen. Sikorski, Gen. Charles de Gaulle led the exiled Free French forces in the Allied camp, and he also often took positions that were considered very problematic for Churchill and the Britain government. As a consequence of these sharp political disagreements, the private papers and diaries of the latter indicated that they sometimes considered the physical elimination of the troublesome French leader. And three months before Sikorski's mysterious death, de Gaulle very narrowly escaped a similar fate when his own personal plane was sabotaged, a near-fatal accident that led him to henceforth avoid any further flying in Britain.

Admiral François Darlan served as commander-in-chief of the Vichy French armed forces, and a few months before de Gaulle's mishap, he had come to an agreement with the top Allied military leadership, facilitating their invasion of French North Africa in exchange for being promised a top role in the new civil administration they would establish. But Darlan had spent years collaborating with the Germans under Vichy, so this deal proved extremely unpopular with much of the American media, which blasted the Allied leaders for having made it. This political backlash only subsided when Darlan was suddenly assassinated, with Irving providing strong evidence that the Allies arranged his elimination.

In another example of this same pattern, Chinese Nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek was publicly lauded throughout the war by the Western media as the heroic head of one of the Big Four Allied powers. But his difficult behavior led the American government to consider his assassination on two separate occasions. McMeekin reported that in late 1943 American military commanders even planned out the exact details of the fatal plane crash that would eliminate Chiang, though their plot was ultimately not carried out.

Drawing mostly upon private papers and official documents, Irving's book described numerous other such assassination projects by the British leaders. These even included contingency plans for the liquidation of their own former King Edward VIII, now Duke of Windsor and brother of the reigning British monarch King George VI.

The list of all these very high-profile Allied assassination plots, whether successful, unsuccessful, or aborted, is a long one, and arranging fatal plane crashes was apparently a favored technique. Given these facts, Sikorski's death under exactly such circumstances at the very height of his bitter conflict with top Allied leaders over Katyn seems rather unlikely to have been purely accidental.

The Wikipedia page on the Katyn Forrest Massacre runs more than 14,000 words and includes over 150 source references. But that lengthy account provides no mention whatsoever of the looming 1940 Allied attack on the USSR that had probably prompted Stalin's lethal decision nor the sudden death of Gen. Sikorski that was a likely consequence of the controversy that erupted after the mass graves were eventually discovered in 1943.

Such silence seems typical of most of our World War II histories. The story of Katyn is usually mentioned, sometimes even prominently, but the other dots are only very rarely connected.

This was the approach taken by acclaimed military historian Chris Bellamy when he published Absolute War in 2007, with his 800 page work featuring glowing cover-blurbs that characterized it as the "authoritative" account of the role of Soviet Russia in the Second World War. Timothy Snyder's very widely praised 2010 bestseller Bloodlands focused on that same topic and won more than a dozen international awards, providing a very detailed narrative of Stalin's massacre of the imprisoned Polish officer corps and the later 1943 controversy, but never even mentioned Sikorski's death.

William Shirer's classic but notoriously slanted 1959 tome The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich ran nearly 1,300 pages but avoided all mention of the Soviet massacre of the Polish officer corps or the highly successful Nazi propaganda campaign when Germany discovered the mass graves in 1943, let alone Sikorski's death. Much more surprisingly, the same total silence was found in the 900 pages of Richard Overy's 2004 book The Dictators that carried the subtitle "Hitler's Germany, Stalin's Russia."

Given the tremendous importance of both the Katyn Massacre and the 1943 political controversy, I think that such striking omissions serve as rather useful indicators of the degree of bias found in those quite hefty accounts of the Eastern Front of World War II.

A very rare exception to this pattern of silence came in Evan Mawdsley's World War II: A New History, published in 2009 by Cambridge University Press, a work that I only very recently came across and read. Prof. Mawdsley's previous books had generally been on Soviet history, and I noticed that his account of the overall global conflict sometimes strayed into highly controversial territory, such as his surprisingly respectful discussion of the Suvorov Hypothesis. Although his text ran less than 500 pages, he devoted more than a full page to a boxed item providing a good summary of the story of the Katyn Massacre, even mentioning Sikorski's death in a plane crash, though without any suggestion of foul play.

The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising and the Holocaust

In reading all these different accounts of the international controversy following the discovery of the mass graves at Katyn, I noticed something that none of the authors had highlighted.

Massacres have hardly been unknown during brutal wars and the Soviet government had become especially notorious in that regard. Prisoners captured in battle have sometimes been slaughtered soon afterward.

But no other example in modern history came to my mind in which sizable numbers of captured POWs who had already been held for many months in prison camps were then taken out and summarily executed, each of them individually shot in the back of the head.

When we consider that the dead numbered more than 20,000 and that they constituted the military and civilian elite of Polish society, the Katyn Forrest Massacre must surely have been regarded as the most appalling European war-crime of the last several centuries. Indeed, by some measures this methodical, cold-blooded execution of so many POWs might rank as one of the worst such atrocities in all of recorded history.

Moreover, by the time the facts became known in 1943, the government of the killers and that of their victims had become less than comfortable military allies in the war against Nazi Germany.

On April 13th, German radio began promoting the appalling story, and it soon became their most successful wartime propaganda project. If the hundreds of thousands of Polish troops serving in Allied armies or the millions of Polish-American voters had become fully aware and convinced of those true facts, the entire course of World War II might have followed a very different trajectory.

Such political risks must surely have been obvious to Stalin. The Allied governments quickly followed his lead and declared that the Germans had been responsible, and all the Western media outlets either echoed those official falsehoods or else merely reported the conflicting German and Soviet accusations. But everyone in a position of leadership knew the reality of what had actually happened, and Sikorski immediately began trying to break through that wall of political and media obfuscation. A few months later, Sikorski was dead and the danger had subsided, but in April 1943 Stalin would have greatly feared that matters might soon take a far more dangerous turn.

So the Soviet government was faced with the difficult challenge of somehow deflecting Western attention away from what was probably the worst war-crime in modern world history, a war-crime that he had committed against his own current allies.

Aside from ironclad, emphatic denials and loud accusations that the Germans had been responsible, the obvious strategy was for the Soviets to begin generating and circulating stories of horrendous Nazi war-crimes, perhaps even war-crimes of vastly greater magnitude. So even if the true facts regarding the summary execution of more than 20,000 Polish officers did somehow manage to come out and become widely believed, perhaps those other, far greater Nazi crimes would still reduce Katyn to total insignificance.

In reading the McMeekin book, I noticed that the many pages describing the controversy produced by the discovery of the mass graves at Katyn were immediately followed by a discussion of the even more horrific Jewish Holocaust.

The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising

This sort of juxtaposition is not uncommon in our history books. One obvious reason is that just six days after the Germans unleashed their Katyn propaganda campaign, the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising erupted, the greatest Jewish revolt against Nazi occupation forces during all of World War II. For generations, the account of the hopeless stand of the courageous Warsaw Ghetto Jews against their murderous Nazi foes has become one of the most famous stories of the war, always closely associated with the Holocaust.

Astonishing coincidences involving momentous geopolitical events strike me as extremely suspicious. We have Germany launching its most important propaganda campaign of the war on April 13th and then on April 19th the largest Jewish uprising of that same conflict suddenly broke out. I find it very difficult to believe that there was no causal connection between these two important events.

The notion that word of a 1940 Soviet massacre of Polish Gentile military officers somehow inspired the Jews of Warsaw to revolt against their Nazi oppressors in 1943 makes absolutely no sense and can be safely dismissed.

Another obvious possibility to consider is that Goebbels had expected that a major Jewish uprising would soon occur in Warsaw and deliberately timed his Katyn propaganda campaign to distract world attention from that looming event. But according to all accounts, that sudden outbreak of violent Jewish resistance completely took the Germans by surprise, and their original commander was quickly replaced because of his ineffective performance.

Therefore, the remaining possibility is that the German propaganda campaign centered on murdered Polish officers somehow triggered the seemingly unrelated Ghetto uprising of oppressed Jews six days later, an uprising that was spearheaded by a left-wing Jewish group called ZOB. I think we may safely assume that Stalin's Soviet agents had considerable influence within ZOB, and he might have urgently deployed all of that influence to provoke a Jewish uprising that would help deflect public attention away from the growing Katyn story, with the impact magnified by the hugely disproportionate Jewish role in Western media outlets.

The very comprehensive Wikipedia account of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising runs more than 10,000 words, and I carefully read it. Wikipedia articles may or may not be accurate, but they generally reflect our official current narrative of major historical events.

Although numerical estimates differ, by April 1943 the Germans had already removed roughly 85% of the Jews from that Ghetto, transporting them away to the East, so no one expected that the remaining 15% would suddenly launch a violent revolt. That revolt seems to have been very poorly planned and was completely hopeless, with 13,000 Jews eventually being killed against only 17 Germans. But Stalin could hardly have cared less about such very lop-sided casualty figures if the weeks-long German assault on the Jewish Ghetto helped draw world attention away from the Katyn story that was so potentially dangerous to him.

According to our traditional narrative, the Jews deported from the Warsaw Ghetto whether before or after the failed uprising were sent to their deaths, shipped off to Treblinka or other Nazi extermination camps, where they were all gassed.

These hundreds of thousands of murdered Jewish victims constituted an important portion of the Holocaust, a crime against humanity so enormous that the methodical execution of more than 20,000 Polish officers barely registers in our history textbooks by comparison. Yet if not for the Holocaust, that latter war-crime would otherwise be recognized as probably the greatest in modern world history and would surely have heavily dominated our subsequent accounts of the war.

In my casual explorations, I discovered an interesting association between those two terrible crimes. According to Wikipedia, the first comprehensive report of a Holocaust death camp reached the West when a Polish officer named Witold Pilecki escaped from Auschwitz in 1943. His detailed account included many of the central elements of what would eventually became our standard Holocaust narrative, and Pilecki was the first person who ever provided these facts:

The report includes details about the gas chambers, "Selektion", and sterilization experiments. It states that there were three crematoria in Auschwitz II capable of cremating 8,000 people daily.

Obviously, the industrialized extermination of innocent Jewish men, women, and children at a rate of up to 8,000 per day immediately reduced the Katyn Forrest Massacre to a mere bagatelle.

And by an absolutely astonishing coincidence, Pilecki escaped from Auschwitz and first informed the world of the ongoing Holocaust on April 26, 1943, less than two weeks after the Germans launched their Katyn Massacre propaganda campaign.

According to our standard Timeline of the Holocaust, Auschwitz had begun gassing Jews with Zyklon B and then cremating all their bodies on September 3, 1941. But for the next twenty months, the entire world remained totally unaware of those horrific events that were transpiring in the heart of Europe, events that only first came to light in the immediate aftermath of the German discovery of the mass graves at Katyn.

Perhaps this timing was purely coincidental. Perhaps Stalin was extraordinarily lucky in that the public disclosure that he had committed the worst wartime atrocity in modern European history was immediately followed by the public disclosure that his Nazi adversaries were currently committing a vastly greater wartime atrocity of their own. But such remarkable coincidences leave me very suspicious. The details of the Pilecki Report presented by Wikipedia provide not the slightest hint of any Soviet involvement, but I still strongly suspect that a hidden Soviet hand may have been responsible for those sudden Holocaust revelations.

Ironically enough, according to that same Wikipedia article, the Allies generally ignored and dismissed Pilecki's report, regarding it as exaggerated wartime propaganda.

Such a reaction was hardly uncommon at the time, as was later documented by the prominent Holocaust scholar Deborah Lipstadt in her important 1986 book Beyond Belief. In that work, she explained that throughout the entire course of World War II, both our mainstream media and the Allied leaders who informed it treated all the stories they received of what we now call the Holocaust with huge disdain, dismissing those accounts as fraudulent or wildly exaggerated wartime propaganda.

One final, fascinating item buried in Irving's 1967 Sikorski book may help to explain why the Allied governments so completely disregarded the Pilecki Report that described the massive gassing and cremations of the Jews at Auschwitz, as well as the subsequent accounts of the Holocaust that they later received.

According to Irving, during the preceding days and weeks, the Polish underground army had printed thousands of somewhat satirical propaganda posters and distributed them all across Poland. These were purportedly by the Nazi occupation authorities, who boasted that unlike the brutal Bolsheviks, they relied upon German science to efficiently and humanely exterminate the Poles at Auschwitz using gas chambers rather than bullets:

In this connection, the Generalgouvernement has ordered that a parallel excursion be organised to the concentration camp at Auschwitz for a committee of all ethnic groups living in Poland. The excursion is to prove how humanitarian, in comparison with the methods employed by the Bolsheviks, are the devices used to carry out the mass extermination of the Polish people. German science has performed marvels for European culture here; instead of a brutal massacre of the inconvenient populace, in Auschwitz one can see the gas and vapour chambers, electric plates, etc., whereby thousands of Poles can be assisted from life to death most rapidly, and in a manner which does honour to the whole German nation.It will suffice to indicate that the crematorium alone can handle 3,000 corpses every day.

Thus, the Pilecki Report, the first solid description of the details of what we now call the Holocaust, seems to have largely been plagiarized from a semi-satirical Polish propaganda poster, merely changing the victims from Poles to Jews and doubling or tripling the daily totals.

Throughout the remaining course of the war and the Nuremberg Tribunals that followed immediately afterward, the American government retained its official public position that the Nazis rather than the Soviets had been responsible for the Katyn Forrest Massacre, generally not actively promoting that theory but never publicly challenging it. So when the Soviet prosecutors charged the defendants at Nuremberg with that horrific crime, the American judges and prosecutors merely remained silent. Numerous documents demonstrate that the private beliefs of the Allied leaders were entirely different than their public posture.

But in 1951, the American government finally reversed its position and declared that the Germans had been correct all along in claiming that the Soviets had committed that horrible crime.

As it happens, that same year, a well-regarded American university professor named John Beaty published an important book entitled The Iron Curtain Over America that became a huge bestseller in its day, but has long since been totally forgotten.

As I explained earlier this year:

Beaty had spent his wartime years in Military Intelligence, being tasked with preparing the daily briefing reports distributed to all top American officials summarizing available intelligence information acquired during the previous 24 hours, which was obviously a position of considerable responsibility.As a zealous anti-Communist, he regarded much of America's Jewish population as deeply implicated in subversive activity, therefore constituting a serious threat to traditional American freedoms. In particular, the growing Jewish stranglehold over publishing and the media was making it increasingly difficult for discordant views to reach the American people, with this regime of censorship constituting the "Iron Curtain" described in his title. He blamed Jewish interests for the totally unnecessary war with Hitler's Germany, which had long sought good relations with America, but instead had suffered total destruction for its strong opposition to Europe's Jewish-backed Communist menace.

Then as now, a book taking such controversial positions stood little chance of finding a mainstream New York publisher, but it was soon released by a small Dallas firm and then became enormously successful, going through some seventeen printings over the next few years. According to Scott McConnell, founding editor of The American Conservative, Beaty's book became the second most popular conservative text of the 1950s, ranking only behind Russell Kirk's iconic classic, The Conservative Mind.

Books by unknown authors that are released by tiny publishers rarely sell many copies, but the work came to the attention of George E. Stratemeyer, a retired general who had been one of Douglas MacArthur's commanders, and he wrote Beaty a letter of endorsement. Beaty began including that letter in his promotional materials, drawing the ire of the ADL, whose national chairman contacted Stratemeyer, demanding that he repudiate the book, which was described as a "primer for lunatic fringe groups" all across America. Instead, Stratemeyer delivered a blistering reply to the ADL, denouncing it for making "veiled threats" against "free expression and thoughts" and trying to establish Soviet-style repression in the United States. He declared that every "loyal citizen" should read The Iron Curtain Over America, whose pages finally revealed the truth about our national predicament, and he began actively promoting the book around the country while attacking the Jewish attempt to silence him. Numerous other top American generals and admirals soon joined Stratemeyer in publicly endorsing the work, as did a couple of influential U.S. senators, leading to its enormous national sales.

Beaty's book also contained a minor aside that was totally ignored at the time but in retrospect may have had great significance.

In a couple of paragraphs, Beaty casually dismissed what we today call the Holocaust as long-discredited wartime atrocity-propaganda that almost no one still believed to be true. And oddly enough, although the ADL, other Jewish activists, and liberal academics all fiercely denounced his book on numerous grounds, none of them seemed to have challenged or even noticed his very explicit declaration of "Holocaust denial." Beaty was also scathing toward the Nuremberg Tribunals, denouncing them as dishonest judicial proceedings that constituted a "major indelible blot" upon America and "a travesty of justice," a farce that merely taught the Germans that "our government had no sense of justice."

- The True History of World War II

- Prof. John Beaty and The Iron Curtain Over America

- Ron Unz • The Unz Review • June 2, 2025 • 14,300 Words

During the war, Classics Prof. Revilo P. Oliver had led a large 175 person code-breaking group in the War Department, and he was decorated for his outstanding service in that conflict. Oliver later became a leading early contributor to William F. Buckley Jr.'s National Review and a co-founder of the John Birch Society, and in 1981, he published his personal memoirs and a collection of his essays under the title America's Decline. In that work, he took exactly the same position as Beaty on those matters, but did so at much greater length, condemning Nuremberg and ridiculing the Holocaust as the most absurd sort of fraudulent wartime propaganda.

Much more recently, a weighty volume published in 2000 by mainstream historian Joseph Bendersky provided some further insight on these matters. His decade of exhaustive archival research demonstrated that many of the sentiments publicly expressed by Beaty and Oliver were privately shared by most of their former wartime colleagues, being quite widespread in such circles.

Prof. Bendersky was an academic specialist in Holocaust Studies, so it was hardly surprising that his longest chapter focused upon that particular subject, as did another closely related one.

In producing his text, Bendersky had exhaustively examined the personal papers and correspondence of a hundred-odd Military Intelligence officers and their top commanding generals. But a careful reading of those two chapters revealed that he was apparently unable to find a single one of those individuals who expressed his belief in the reality of the Holocaust, suggesting they probably shared the views that their former colleagues Beaty and Oliver had explicitly declared in their published books.

There are some intriguing indications that the top Allied leaders may have quietly held similar views. French academic Robert Faurrison became a prominent Holocaust Denier in the 1970s, and in 1998 he made an extremely interesting observation regarding the lengthy histories and memoirs of Churchill, Eisenhower, and De Gaulle:

Three of the best known works on the Second World War are General Eisenhower's Crusade in Europe (New York: Doubleday [Country Life Press], 1948), Winston Churchill's The Second World War (London: Cassell, 6 vols., 1948-1954), and the Mémoires de guerre of General de Gaulle (Paris: Plon, 3 vols., 1954-1959). In these three works not the least mention of Nazi gas chambers is to be found.Eisenhower's Crusade in Europe is a book of 559 pages; the six volumes of Churchill's Second World War total 4,448 pages; and de Gaulle's three-volume Mémoires de guerre is 2,054 pages. In this mass of writing, which altogether totals 7,061 pages (not including the introductory parts), published from 1948 to 1959, one will find no mention either of Nazi "gas chambers," a "genocide" of the Jews, or of "six million" Jewish victims of the war.

And as I went on to explain earlier this year:

Similarly, the voluminous published diaries of Secretary of Defense James Forrestal and Gen. George Patton along with the wartime journals of Charles Lindbergh contain no hint of the monumental event that we today call the Holocaust.Meanwhile, the diary of another prominent figure provided a very surprising perspective on that era. A few years ago, the 1945 diary of a 28-year-old John F. Kennedy travelling in post-war Europe was sold at auction, and the contents revealed his rather favorable fascination with Hitler. The youthful JFK predicted that "Hitler will emerge from the hatred that surrounds him now as one of the most significant figures who ever lived" and declared that "He had in him the stuff of which legends are made." These sentiments are particularly notable for having been expressed just after the end of a brutal war against Germany and despite the tremendous quantity of hostile propaganda that had accompanied it.

A decade later when Kennedy had reached the U.S. Senate, he won the Pulitzer Prize for his 1956 bestseller Profiles in Courage, devoting one of his chapters to praising Republican Sen. Robert Taft for his public condemnation of the legal proceedings at Nuremberg. This suggested that Kennedy's views on many of these matters may not have been so very different from those of Beaty or Oliver.

Despite all those questions and some rather suspicious silences, over the last couple of generations, the Holocaust has assumed a monumental place in Western societies, so much so that it often even overshadows World War II, the colossal military conflict during which it occurred.

For example, we just recently passed the anniversary of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor that took our country into that war, an event that once loomed very large in American public life. Yet Hollywood has only produced about a half-dozen films on that incident that killed more than 2,400 Americans on our own soil, but hundreds on the Holocaust that took place thousands of miles away in Eastern Europe with none of the victims being American.

Admittedly, that extreme skew in coverage can arguably be justified by the factual aspects of the Holocaust, which are so completely astonishing. As I explained in a long 2018 article on that topic:

Over the years, Holocaust scholars and activists have very rightfully emphasized the absolutely unprecedented nature of the historical events they have studied. They describe how some six million innocent Jewish civilians were deliberately exterminated, mostly in gas chambers, by one of Europe's most highly cultured nations, and emphasize that monstrous project was often accorded greater priority than Germany's own wartime military needs during the country's desperate struggle for survival. Furthermore, the Germans also undertook enormous efforts to totally eliminate all possible traces of their horrifying deed, with huge resources expended to cremate all those millions of bodies and scatter the ashes. This same disappearance technique was even sometimes applied to the contents of their mass graves, which were dug up long after initial burial, so that the rotting corpses could then be totally incinerated and all evidence eliminated. And although Germans are notorious for their extreme bureaucratic precision, this immense wartime project was apparently implemented without benefit of a single written document, or at least no such document has ever been located.Lipstadt entitled her first book "Beyond Belief," and I think that all of us can agree that the historical event she and so many others in academia and Hollywood have made the centerpiece of their lives and careers is certainly one of the most extremely remarkable occurrences in all of human history. Indeed, perhaps only a Martian Invasion would have been more worthy of historical study, but Orson Welles's famous War of the Worlds radio-play which terrified so many millions of Americans in 1938 turned out to be a hoax rather than real.